Civilizations endure not through battles won or lost, but through the institutions they build to preserve and extend knowledge. Bharat’s story has always rested on this foundation, from the ancient universities of Nalanda and Vikramashila to the scholarly networks of Banaras, Kashmir, and Bengal.

The colonial rule and foreign invasions fractured this continuity, reducing universities in India to examination boards modelled on London, designed to produce clerks rather than thinkers.

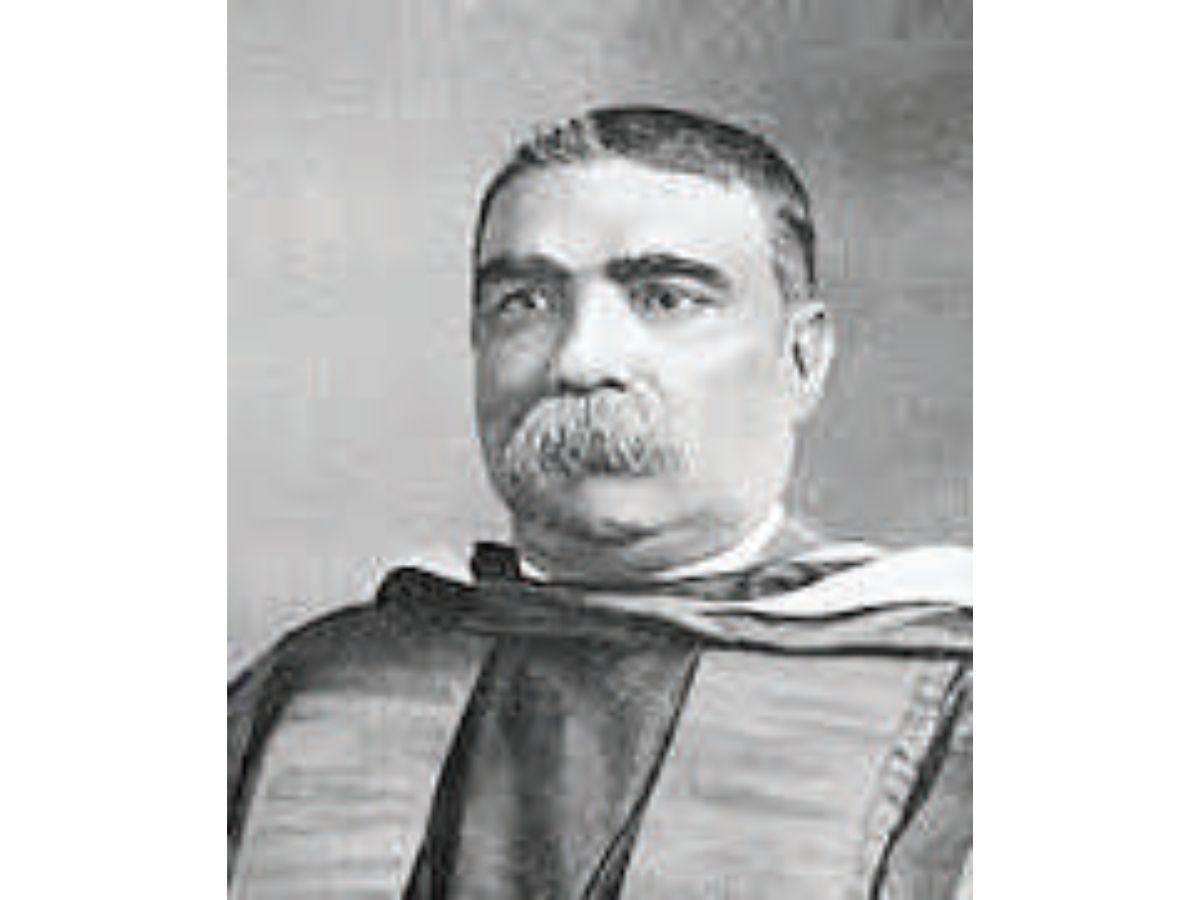

Here, figures like Ashutosh Mukherjee (1864-1924) assume their true significance. Known as Banglar Bagh (the Bengal Tiger), Mukherjee was a jurist of formidable reputation and a noted mathematician of rare talent. For most Indians, his name may sound unfamiliar. Yet, his legacy as one of modern India’s most determined institution builders remains profound and relevant today.

His leadership as Vice-Chancellor of Calcutta University transformed the university from a degree-granting office to serve the colonial master into a global research university, allowing platforms for Indians to display their intellectual capital. In this sense, he embodied the essence of what we now describe as the Indian Knowledge Systems (IKS) approach—conceptualising knowledge in Bhartiya civilizational traditions, yet open to global currents, while being unafraid of intellectual ambition.

Making of a Research University

When Ashutosh assumed charge as Vice-Chancellor in 1906, universities in India were under siege. The Curzon reforms of 1902 had sought to clip their autonomy, branding them hotbeds of sedition. Most were content to serve as colonial instruments, affiliating colleges and conducting examinations.

Ashutosh disagreed with such an approach. In his 1907 convocation, he declared that the university would no longer be “just an institution issuing certificates” but a centre of learning and expanding the frontiers of knowledge. Mukherjee matched rhetoric with action.

Under his leadership, Calcutta University established postgraduate departments and disciplines in niche areas (at that time) like comparative literature, anthropology, applied psychology, industrial chemistry, ancient Indian history and culture, and Islamic culture. He ensured teaching and research in Indian languages—Bengali, Hindi, Sanskrit, and Pali—all were granted equal standing.

At a time when colonial administrators dismissed Indians as creators of knowledge, he promoted and nurtured indigenous knowledge. Mukherjee restored it to the heart of university life while simultaneously pushing the frontiers of modern science.

The roster of scholars he brought together reads like a roll call of India’s 20th-century intellectual renaissance. C.V. Raman, Asia’s first Nobel Laureate in science, worked under his patronage. S.N. Bose, after whom bosons in atoms are named, found encouragement in his vision. Meghnad Saha, who formulated the Saha ionization equation, built his career in these halls. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan taught philosophy, while historians like R.C. Majumdar and H.C. Raychaudhuri shaped the discipline of Indian history. Jurists such as Radhabinod Pal, known for his dissent at the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, were also part of this ecosystem.

What distinguished Ashutosh was not just the recruitment of great minds but his ability to create a culture of intellectual confidence. Scholars from all castes, classes, communities, and even nationalities worked together. Europeans like George Thibaut shared space with Indian linguists like S.K. Chatterji.

He set up the University College of Science (Rajabazar Science College), the University College of Law, and founded the Ashutosh College in 1916. These were not bureaucratic expansions but acts of vision that laid the groundwork for India’s later advances in physics, chemistry, mathematics, and history.

The French scholar Sylvain Lévi, astonished by his achievements, remarked: “Had this Bengal Tiger been born in France, he would have exceeded even Georges Clemenceau. Ashutosh had no peer in the whole of Europe.”

And yet, Ashutosh’s influence was not confined to academics. He mentored Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose during his student days, shielding him from colonial retribution. He inspired Shyama Prasad Mukherjee, who later became a leading nationalist voice. In nurturing such figures, Ashutosh linked the world of scholarship with the world of politics, reminding us of what should be obvious yet remains elusive in academia: intellectual courage and national leadership are often intertwined.

Our Cultural Amnesia

Why then has Ashutosh faded from collective memory? Independent India, eager to foreground political movements, often neglected those who worked quietly to build an intellectual infrastructure. The humiliation of Gandhi on a train in South Africa is recounted endlessly, but the equally telling anecdote of Ashutosh’s train journey is rarely known.

The incident involved a British planter throwing his sandals out of the train. Mukherjee’s response reflected a confident yet polite Indian. He calmly took the planter’s coat and replied that the planter’s coat would fetch his sandals.

This may be striking in Gandhi’s story in many ways, but what’s obvious here is how Ashutosh responded to humiliation with humour and confidence instead of turning the other cheek.

As a result of this wilful effort to overlook and suppress the likes of Mukherjee, post-Independent Bharat has inherited an impoverished understanding of nation-building. We know better now that political independence without intellectual self-confidence is fragile.

Ashutosh, like Madhusudan Das (Odisha) or P.C. Ray (of Bengal), understood that a free India would be secure only when its universities, laboratories, and libraries matched the world’s best. His donation of nearly 80,000 books to the National Library, his presidency of the Indian Science Congress in 1914, and his refusal to compromise when conditions were imposed on his reappointment as Vice-Chancellor—all testified to his belief that institutions must be built on integrity and choice, not convenience.

The lesson from his legacy today is unmistakable. As India speaks of becoming a Viksit Bharat by 2047, development cannot be reduced to GDP numbers. It rests equally on the strength of our educational institutions. We need to recognise whether our universities can foster originality, whether our research can lead the world, and whether our intellectual traditions can coexist with modern scientific inquiry. This is precisely what the IKS framework insists upon: education anchored in India’s civilizational ethos yet unafraid to innovate.

Remembering the Bengal Tiger

Ashutosh Mukherjee embodied the principle that institutions outlast individuals. His life demonstrated that courage in education and action is as vital as courage in politics. He proved that a university could be at once global and indigenous, modern and rooted.

He showed that a leader’s task is not only to excel personally but to create conditions where others may flourish. By recognising his legacy, India rediscovers a missing strand of its own greatness. It acknowledges that freedom was secured not only by marches and fasts but also by classrooms and laboratories.

It learns that true national confidence arises when knowledge is nurtured, protected, and allowed to expand. The Bengal Tiger’s roar must not fade into silence. For a nation seeking its place among the world’s leaders, remembering the likes of Ashutosh Mukherjee is not a sentimental idea but a strategy. His model of fearless, inclusive, and visionary institution-building remains the foundation on which a truly Viksit Bharat can stand.

Prof. Santishree Dhulipudi Pandit is the Vice-Chancellor of JNU.