Ottawa: There are weeks in politics when events accumulate rather than unfold, when gestures, absences, and carefully chosen words matter as much as treaties signed or tariffs lifted. The week of Prime Minister Mark Carney’s visit to Beijing was one such moment. It began with the quiet recall of two Liberal MPs from a parliamentary visit to Taiwan, continued through a cautious thaw in Canada-China relations, and ended with Ottawa speaking openly—if still carefully—about a “new world order” taking shape around us.

To treat these events as isolated would be a mistake. Together, they form a coherent response to a world that has become less predictable, less rulebound, and far less forgiving of middle powers that fail to adapt.

The immediate backdrop is Washington. Under Donald Trump, American foreign and trade policy has become episodic, transactional, and increasingly indifferent to allied sensitivities. Canada has felt this acutely. From steel and aluminium tariffs to repeated threats against the automotive sector and agriculture, the message from the White House has been unmistakable: proximity is no longer protection.

As Reuters and the Globe and Mail have documented repeatedly, Canadian officials now operate under the assumption that U.S. trade policy may change with a press release, a rally, or a mood swing. For business, such unpredictability is corrosive. For alliances, it is destabilising. For a country whose prosperity depends on trade, it is untenable and Canada was no longer willing to play the victim card but rather set itself on a bold new path as a middle power that has truly arrived under this Prime Minister.

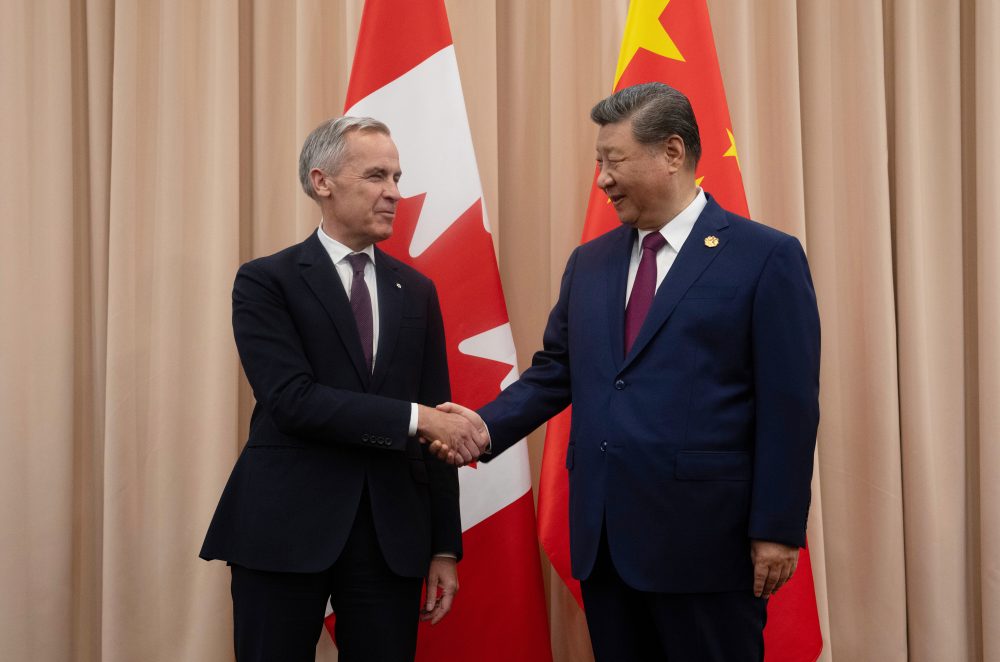

It is against this backdrop that Carney arrived in Beijing, Canada’s first Prime Minister to do so in nearly a decade. The visit yielded tangible, if modest, outcomes. China agreed to reduce tariffs on Canadian canola and reopen agricultural channels, long closed after the diplomatic freeze that followed the arrest of Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou. Saskatchewan Premier Scott Moe, who has pressed relentlessly for market access for prairie farmers, welcomed the move as overdue realism. CBC and Reuters both noted that for Canadian agriculture, China remains not a luxury market but a structural necessity.

Yet the visit was never only about canola or electric vehicles. Its real significance lay in signalling that Canada is no longer prepared to anchor its economic future to a single, increasingly unreliable partner. Saskatchewan farmers were winners but the Ontario auto industry, according to Premier Doug Ford, were losers.

When Bloomberg’s Helen Platt asked Carney to explain his reference to a “new world order,” the Prime Minister was unusually candid. The global system, he said, is still determining what will govern trade, finance, and regulation. The multilateral architecture built around institutions such as the WTO and IMF is being eroded—”undercut,” in his words—and replaced by coalitions, bilateral arrangements, and sector-specific alignments. These will not govern the world, Carney observed, but parts of it.

That distinction matters; but as an architect of the WEF’s New World Order that put China at the helm, U.S. unravelling of this architecture was a direct threat to the PM’s club of those crafting a green future. One that Trump has flatly rejected. It was not the language of alignment with China. It was the language of adaptation.

China, for its part, has been explicit about what it hopes to gain. As PBS and Chinese state media reported, Beijing views Canada as a useful counterweight to U.S. influence, a G7 economy willing to engage pragmatically rather than ideologically. Ottawa has been careful not to reciprocate that framing. The recall of MPs from Taiwan ahead of the visit reported by iPolitics, was less a concession than a signal of discipline: Canada would not allow symbolic gestures to derail a broader strategic recalibration.

This recalibration has been reinforced by voices on both sides of the border. Former U.S. National Security Advisor John Bolton, speaking in recent commentary, warned that Canada gains nothing by mirroring Trump’s confrontational style. His criticism of Carney’s earlier apology over an anti-tariff advertisement was revealing, not because it was persuasive, but because it underscored the point: under Trump, there is no stable script for allies to follow.

It is here that Carney’s own background becomes relevant and often misunderstood. His previous leadership at Brookfield Asset Management, a firm with substantial exposure to China, has attracted predictable scrutiny. Yet the assumption that this creates a conflict of interest misreads both the man and the moment. Carney’s financial interests, while aligned with China, suggest that with stability, market access, and the durability of rules—however fragmented they may now be—will provide wins for his former corporation and for Canadians.

That will need to be tested as the trust placed in Beijing is both uncomfortable to almost everyone in the diaspora community that I spoke with over the last 24 hours. He gains politically and personally only if Canada succeeds in navigating this fractured environment without sacrificing its economic base.

That alignment does not make the strategy risk-free. Security concerns remain unresolved. Chinese interference and transnational repression affecting diaspora communities in Canada are not theoretical. Nor are they marginal. While Carney has confirmed that the case of Jimmy Lai and broader human rights concerns were raised during discussions consistent with G7 positions reported by international media, the fact remains that such issues rarely travel far in commercial negotiations. Trade opens doors; values tend to linger in the antechamber.

Carney disappointed tremendously here and his and his team’s naivety in a belief that China could be trusted is totally misplaced. This is the central tension of Canada’s current posture. In seeking diversification, Ottawa risks normalising engagement without securing meaningful leverage on civil liberties, political repression, and security guarantees. The danger is not capitulation, but gradual accommodation as we have watched in Canada for two decades. Each concession appears reasonable until the cumulative cost becomes clear and this once again has been borne out on Taiwan, Tibet, Xinjiang and Hong Kong; but I trust Xi has had an epiphany and our PM secured his apology and a clear change of Chinese policy. Not.

Nor will Washington be indifferent. As the next review of CUSMA approaches, U.S. officials will scrutinise Canada’s external alignments with renewed intensity. Any perception that Ottawa is facilitating access to U.S. markets for Chinese goods produced with sanctioned inputs or forced labour will provoke a response. The rules-based order may be fraying, but enforcement has not disappeared—it has simply become more selective.

Still, this is a narrow path. Canada is not choosing between the United States and China. It is choosing how much autonomy it can realistically sustain between them. That autonomy will be tested not by communiqués, but by crises: over Taiwan, over sanctions, over supply chains, and over the rights of people who live within our borders but remain vulnerable to pressure from abroad.

The gravest mistake would be to confuse diversification with insulation. Canada cannot trade its way out of geopolitics and partnering with what many believe is a criminal and corrupt enterprise that values few human rights or freedoms is simply folly. What Canada seems to be doing is attempting to reduce exposure to volatility while buying time to reinforce domestic resilience and perhaps bringing protectionists in DC to their senses as Liberals see the world and calculus.

In this sense, the Beijing visit was neither a pivot nor a betrayal. It was a hedge, undertaken in full view of its risks. The new world order Carney described is not one Canada would have chosen. But it is the one we must now navigate carefully, sceptically, and without illusions. Let the New World Order unfold as it should or is that how Prime Minister Carney wishes it to be? As history unfolds, will this be judged as a masterstroke of statecraft where the US pauses, thinks and adapts, or a strategic gambit that will become untethered by US retaliation based on their national security policy, which aims to solidify hemispheric hegemony for the USA?

Dean Baxendale is Publisher, CEO of the China Democracy Fund and co-author of the upcoming book, Canada Under Siege.