Chicago:

THE RAJAMANDALA

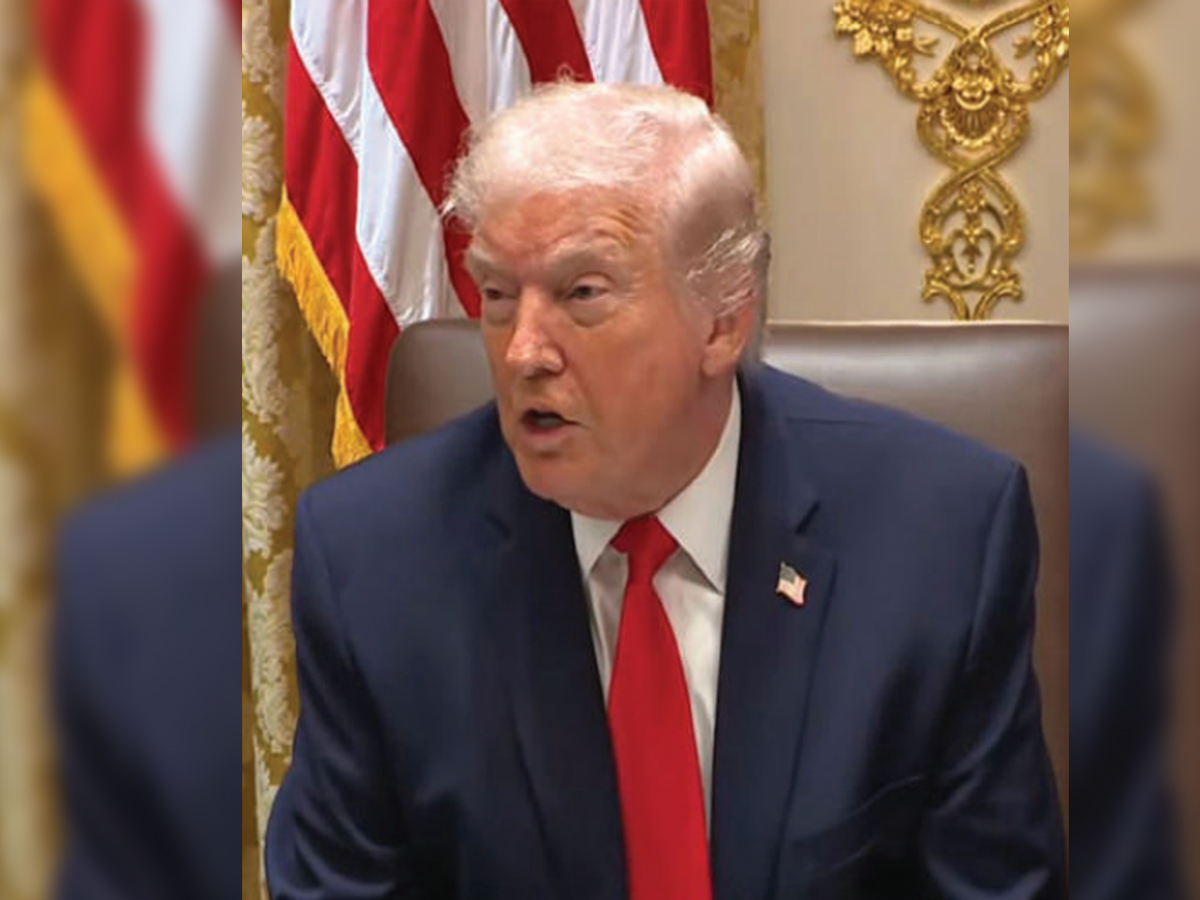

Many domestic and foreign policy observers and analysts interpret the Trump administration’s actions through the lens of strong opposition and disgust towards President Donald Trump and his MAGA (Make America Great Again) political base. Critics of Mr Trump point to the strained relations with America’s allies in Europe, Asia, and across the northern borders as evidence of what they describe as negative traits and policy choices. However, focusing solely on these aspects, especially through Mr Trump’s media persona, may overlook broader challenges in US foreign policy and limit consideration of strategic opportunities.

Television played a significant role in Mr Trump’s rise to political prominence. He frequently seeks out high-visibility opportunities to engage with the media and the public. In contrast to some other leaders, Mr Trump is known more for his performance style than for his oratory. There is a saying among Trump observers: take Trump seriously, not literally. Mr Trump is also a New York businessman and speaks like one. Interested readers might consider the work of sociolinguist Deborah Tannen on New York speech.

Sumedha Verma Ojha, a historian and author, most recently of the book “Chanakya’s Scribe,” analyses Trump’s foreign policy through the Chanakyan framework in the Vak Indian History podcast. “The Kautilyan framework has the central concept of ‘national interest’ which each country aims to pursue. It is a realist view of international relations that each country seeks to better its own situation,” said Verma Ojha, communicating via text messages. She warns that, when discussing the Chanakya framework, one should focus on substantive issues, divorced from the strong emotions Mr Trump elicits among his admirers and critics alike.

The Rajamandala (the circle of kings) is an important Chanakyan (the Arthashastra) concept built around the notion of vijigishu. The Chanakyan vijigishu is the king or the leader of a country who wishes to consolidate and enhance his power through conquests.

The Rajamandala comprises 12 kings or states. There are, however, two ways of understanding the circle of kings. In the first view, there are four main political units: 1) the vijigishu or the king who wishes to expand his empire, 2) the ari or the enemy next door, 3) the madhyama or the state which shares the territory with both the vijigishu and the ari, but is stronger than either, and 4) the udasin or the neutral king. Each of these kings also has a mitra and a mitra-mitra. This classification yields 12 kings in the mandala, arranged in 4 sets of 3.

The other Rajamandala scheme consists of the following 12 kings: 1) vijigishu or the king looking for conquest, 2) ari or the enemy, 3) mitra or the ally, 4) the ari-mitra or the friend of the enemy, 5) the mitra-mitra or friend’s friend, 6) the ari-mitra-mitra or ally of enemy’s ally, 7) the parshnigraha or enemy in the rear, 8) the akranda or the ally of the ally in the rear, 9) the parshanigrahasara or the ally of the enemy in the rear, 10) the akrandasara or the ally of the ally in the rear, 11) the madhyama or the middle kingdom between state and enemy and stronger than both, and 12) the udasin or neutral but stronger than the vijigishu, ari and madhyama.

The goals of enhancing a state’s interests in the international arena, Verma Ojha argues, can be achieved either through brute force or through subtle diplomacy. The Chanakyan framework provides six methods, the sadgunya, of dealing with other constituent states in the circle. They are 1) sandhi or peace, 2) vigraha or hostility, 3) asana or remaining quiet, 4) yana or military expedition, 5) sanshraya or seeking shelter, and 6) dvaidhibhava or a combination of sandhi and vigraha.

Chanakya also lists four upayas, the means of overcoming the opposition: 1) sama or the policy of conciliation, 2) dana or the policy of financial inducement, 3) bhdeda or the policy of dissension, and 4) danda or the use of force.

A NEW WORLD ORDER

As Mr Trump dismantles the old world order while building a new one, readers can see several Chanakyan principles at play.

The rise of “middle power” states and the post-Cold War shift toward multipolarity, combined with China’s spectacular rise, have increasingly challenged the United States, the hegemon, in the global arena. China is already an economic powerhouse, and the US-China military balance has been trending in the wrong direction from the US perspective. Many analysts believe it will take only a few years, not decades, for the US to lose its military advantage to China.

A flawless US military operation in Venezuela significantly reduces Chinese influence in America’s neighbourhood. At the same time, US strikes on Iran’s three nuclear sites demonstrate dominance in the Middle East, far away from home. The US conducted these military actions unilaterally, without meddling from China or Russia, thereby reinforcing its foreign policy advantages.

“Not since Franklin D. Roosevelt has an American president been this powerful or this busy,” writes Walter Russell Mead in his Wall Street Journal column Global View. “But while the storm Mr Trump unleashes is chaotic, there is a certain logic to his path.”

The so-called “rules-based world order,” flawed as it was from the get go, kept the world relatively peaceful for decades. It was, undoubtedly, built on the back of American might. The Europeans were the most prominent beneficiaries of that order as American foreign policy increasingly became Eurocentric. As Americans increasingly came to realize that Europeans were not keeping their end of the bargain and were instead gratuitously issuing virtue signals on liberty, freedom of speech, etc., as well as their woke agenda, the strains in the contract began to creep in.

Mr Trump’s approach to Europe has been direct, highlighting areas of disagreement. With much of its security provided by the US, Europe is more geoeconomically connected to America than ever. The United States can leverage this interconnectedness in geopolitical matters involving Europe. “The reliance puts Europe at a disadvantage in a world of great power competition and weakens its hand in negotiating with Trump on everything from trade to Greenland and Ukraine,” write Tom Fairless and Kim Mackrael in the Wall Street Journal.

Mr Trump’s desire to acquire the island of Greenland may seem politically absurd. However, such attempts and subsequent acquisitions are not an anomaly in American history. Greenland’s significance lies in its strategic location and the abundance of rare earth minerals as the AI war proliferates.

While campaigning for the 2024 presidential election, Mr Trump presented himself as an isolationist who wasn’t keen on continuing with America’s never-ending wars. He did not start a single war in his first term, a rare feat for an American president, was one of the selling points of Mr Trump’s 2024 campaign. But as Mead writes in his column, “[t]his president isn’t retreating from the world. He aims to reshape it.”

TRUMP AND INDIA

While Mr Trump’s attitude towards Europe exposes Europe’s weakness, his treatment of India has strengthened India in strange ways, as evidenced by the recent signing of the Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with the EU.

It has barely been a year since Mr Trump assumed the presidency of the United States. However, in this short one-year period, the excitement over his presidency couldn’t have evaporated any sooner for many in India. Mr Trump’s oft-repeated claim about mediating in a “nuclear war” between India and Pakistan, imposition of tariffs on India, and a slew of racist and Hinduphobic attacks quickly soured the relations between the two countries.

Nothing speaks rivalry better than the India-Pakistan rivalry. Indians, despite their desire to decouple from the Islamic Republic in the international arena, fail to see geopolitics outside of the India-Pakistan binary. Mr Trump’s overtures towards India’s arch-nemesis, along with hints of mediation, have not gone down well with both India’s elites and ordinary citizens.

President Trump’s punitive tariffs on India do nothing to “Make America Great Again.” They only undermine the bipartisan work of both American and Indian leadership over the past three decades to improve relations between the world’s two most powerful democracies.

Mr Trump and his allies have placed significant obstacles in the US-India relationship. Over a billion Indians and approximately 5 million Indian Americans report being surprised and dismayed by statements from Mr Trump’s MAGA base.

Despite efforts, the tariff issue between the US and India remains unresolved. A quick reset and newer common grounds are needed for a better foundation. Towards this end, developing deterrence against China in the Indo-Pacific, blunting Chinese influence among India’s neighbours in the subcontinent (which, to some extent, Pakistan’s proximity to the White House does), and countering Islamist terrorism are promising starting points.

The point remains that Mr Trump’s foreign policy is well understood in the Kautilyan system, according to Verma Ojha. However, the approaches to achieving these goals remain less than desired.

India, on the other hand, has handled its recent upheavals in relations with the US with grace and dignity.

Also, Mr Trump’s retreat on Greenland and in Minneapolis aren’t another one of the TACO—Trump Always Chickens Out—stories. It shows that there is a limit to his power and that checks and balances work.

* Author is a Chicago-based, award-winning journalist.