If you are asked to imagine Mahatma Gandhi addressing a gathering of his followers, you cannot think of any other picture but Gandhi in a seated position unlike most other leaders of his time. The sitting pose is assumed by saints and holy men while discoursing. No wonder Gandhi’s approach to politics was ethical and was based on religious tenets.

And did you know that at the Pune Session in 1895, the 11th President of Indian National Congress, Surendranath Banerjea, spoke uninterruptedly for four hours without referring to any notes in an assembly of around 5,000 people? Almost 20 years previously, Banerjea became the first Indian politician to travel across India by taking advantage of the railways.

Or sample this. A firebrand speaker Tahalram Gangaram from Dera Ismail Khan drew more audience outside the Town Hall of Kolkata with his firebrand oratory exactly when Rash Behari Ghose (1845-1921), a moderate leader, was addressing a public meeting inside the hall against Lord Curzon’s policies.

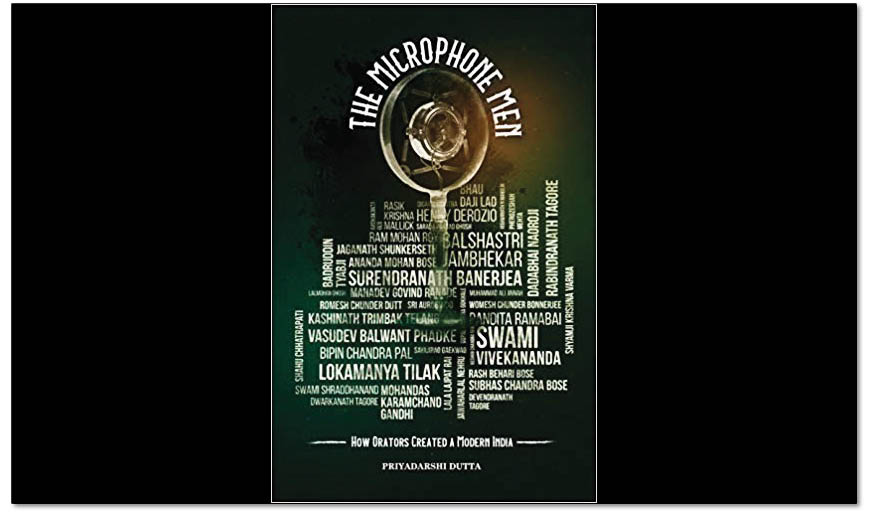

In all the three nuggets above, “speech” is a common factor. These form the part of a book titled The Microphone Men: How Orators Created A Modern India, authored by Priyadarshi Dutta. This seems to be the first book on the “genesis and development” of speech or oratory in India, though there are several collections and anthologies of important historical speeches.

It is surprising that in a country like India, where “Shruti Parampara” or learning through hearing, had always been a tradition, and where oral tradition had flourished in every arena of cultural, spiritual or social life, there has not been a conscious attempt to chronicle the history of oratory. Perhaps the reason is that oratory as a specific discipline remained underdeveloped in India in the pre-modern period. The reason could be that our religious texts were in verse, and except for drama, poetry was the standard form of literature. As Dutta observes in this book, “Literature was mostly set in verse to aid memorizing.”

However, the importance of speech was not lost on our ancient seers. The ancient Tamil classic Kural, by Thiruvalluvar, contains two chapters on the virtues of good speech. “Behold the men that take upon themselves to address an assembly…” The precise dates of Thiruvalluvar are not known but it is estimated that he lived sometime between 3rd and 1st centuries BC.

The author notes that whereas in ancient Greece, it was perfectly common to be loud, abusive, and scornful, the Indian savants viewed things very differently as they thought speech should be untainted by falsehood, rudeness, or dissension. Further, it should be an instrument of enlightenment, happiness and concord. (It seems the contemporary Indian politicians have moved more towards the ancient Greeks if speeches in recent elections were any indication).

The book argues that oratory is essentially a training in thinking rather than talking. A good speech is one that contains good ideas. The author notes that the uprising of 1857 did not have any orators of significance. The near absence of oratory in the 1857 uprising points to a lack of dialogue between the leaders and masses. The leaders came from a social stratum who took the support of the masses for granted without the need to persuade. Thus they were on a different footing from the advocates and legislators of New England states who imparted intellectual leadership to the American Revolution.

In modern India, speechmaking started developing as a vital tool for communication in 1830s—first in Bengal and subsequently elsewhere. The foundation of the Indian National Congress, a pan-Indian Association, was its highest water mark. However, speechmaking soon lost its novelty. With the emergence of Gandhi on the national scene, it assumed an entirely different dimension. The author quotes the Mahatma as saying, “You will never be able merely through the lip to give the message that India, I hope, will one day deliver to the world. I myself have been ‘fed up’ with speeches and lectures.” The occasion was the inauguration of the Banaras Hindu University on 6 February 1916. Dutta concludes that in Gandhi, we encounter a new approach towards speech-making. It became only an aid, not the foundation of his political programme.

Dutta in his book covers different arenas where speechmaking evolved as an effective tool. A chapter titled “Lawmaking Prompts Speechmaking” gives the reader an overview of the various legislations brought by the British which resulted in intense debates and thus produced quality speeches.

In the process of chronicling the history of speechmaking, the book especially mentions events and happenings in the two major cities of Bombay and Calcutta that fast adapted to the modernity that the British brought with them. The Hindu College, which later became Presidency College, became the nursery of public speaking in Calcutta.

Pherozeshah M. Mehta, Badruddin Tyabji and K.T. Telang, famously known as “the Bombay Triumvirate”, were the driving force behind the Bombay Presidency Association. Tyabji made an incisive speech at a public meeting on 28 April 1883 in support of the Ilbert Bill for amending the code of criminal procedure which was being stoutly opposed by the European community in India.

The book hand-holds the reader to various phases of India’s Independence struggle and extensively discusses the role and also the limitations of speechmaking. It is natural that Gandhi’s style of speechmaking forms an important part of this process. The book delves into the radio speeches delivered by Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose and Rash Behari Bose from Germany and East Asia during World War II. The anti-climax is reached in the Muslim League’s campaign for breaking India. There was not only high degree of inflammatory and abusive content in them, but they were also antithetical to the attempts of India’s stalwart orators since the 19th century to unite India.

It must be said that the book has been successful in weaving a unique narrative, wherein the reader comes across all the important events of India’s freedom movement while going through the history of oratory in modern India. It would be appropriate if the author undertakes a similar research into various aspects of speech-making in independent India. There are quite a few errors of proofreading in the book, which the readers can gladly suffer for the quality of its content.

The reviewer retired from a senior position in the Press Information Bureau and currently runs a Hindi e-zine, www.raagdelhi.com, on contemporary society, art and culture.