There is a lot of love in Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood, and quite a bit to enjoy. The screen is crowded with signs of Quentin Tarantino’s well-established ardour—for the movies and television shows of the decades after World War II; for the vernacular architecture, commercial signage and famous restaurants of Los Angeles; for the female foot and the male jawline; for vintage clothes and cars and cigarettes. But the mood in this, his ninth feature, is for the most part affectionate rather than obsessive.

Don’t get me wrong. Tarantino is still practicing a cinema of saturation, demanding the audience’s total attention and bombarding us with allusions, visual jokes, flights of profane eloquence, daubs of throwaway beauty and gobs of premeditated gore. And yet Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood, whose title evokes bedtime stories as well as a pair of Sergio Leone masterpieces, is Tarantino’s most relaxed movie by far, both because of its ambling, shaggy-dog structure and the easygoing rhythm of its scenes.

Though trouble percolates on the horizon and mayhem arrives in the final act, this is fundamentally a hangout movie, a bad-guys-come-to-town Western more like Rio Bravo than High Noon. Above all, it’s a buddy picture about two middle-level entertainment industry workers doing their jobs and making the scene over a few hectic, sunny days in 1969.

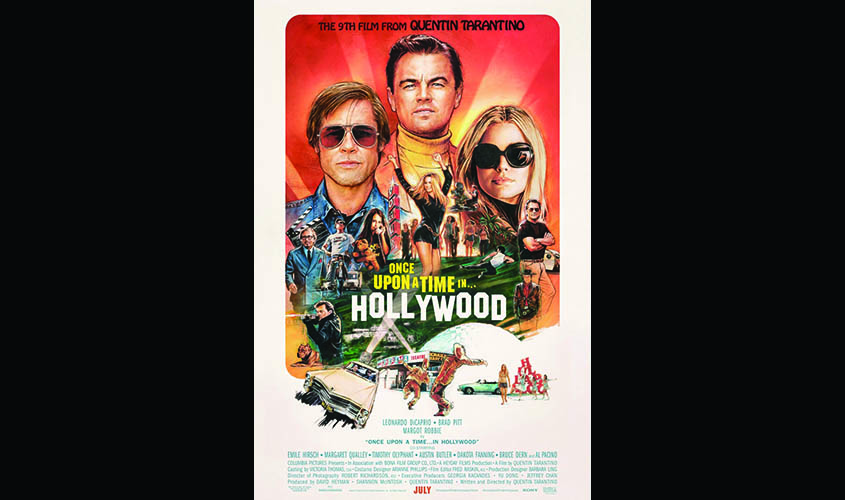

The friendship between Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio) and Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt) functions for Tarantino as both keystone and key. It’s an organising principle and a source of meaning, and a major reason that Once Upon a Time is more than a baby-boomer edition of Trivial Pursuit brought to life.

Unlike many of the people they share the screen with—the period-specific A-list characters include Sharon Tate (Margot Robbie), Steve McQueen (Damian Lewis) and Bruce Lee (Mike Moh)—Rick and Cliff are made-up. Rick is an actor on the downward slope of a moderately successful career. A star in a handful of Westerns and combat pictures, and of a popular TV Western series, he is now mostly cast as a one-episode villain on other people’s shows. He’s considering an offer to make spaghetti Westerns in Italy. (Tarantino supplies perfect fake clips to annotate Rick’s filmography.) Not a has-been, exactly, but not quite what he used to be or might have been.

Cliff is his longtime stunt double, but as Rick’s roles have shifted, his role has changed too. His duties include driving Rick (whose license has been suspended) to and from auditions and sets, performing minor household repairs and generally being available as a sounding board and drinking partner. You can’t really call Cliff a sidekick—we’re talking about Brad Pitt—and he’s not really a servant, either, even though Rick pays him for his time. An older vocabulary is needed: Cliff is a gentleman’s gentleman, a man Friday, a dogsbody, a squire. “More than a brother but less than a wife” is how the movie puts it.

The relationship isn’t defined by money or sex, but by a difference in rank accepted without comment or complaint by both parties. The inequality between the men—Rick lives in a spacious ranch house up in the hills, Cliff in a cluttered trailer down in the valley—is what dignifies their bond, just as the contrast of their temperaments sustains it.

Rick, a sloppy drinker and a furious smoker, wears his feelings close to the surface. He weeps aloud over the state of his career, throws an epic tantrum in his trailer when he messes up a scene and is moved to tears by the exquisiteness of his own acting. Cliff is a different kind of cat—lean, taciturn, self-effacing, slow to anger but capable of serious violence. Some say he’s a murderer; he himself occasionally alludes to a criminal past. Better not to ask. Apart from Rick, his main attachment is to his dog, Brandy, whose loyalty is the mirror of his own. (DiCaprio’s baroque, exuberant emotionalism perfectly complements Pitt’s down-to-the-bone minimalism. They’re both terrific.)

If the guys aren’t quite Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, their companionship nonetheless takes shape within a fundamentally aristocratic social order. Joan Didion, in an essay first published in 1973, described the Hollywood of that era as “the last extant stable society,” and Tarantino’s tableau confirms this view. Life isn’t perfect, but it is coherent. People know their place. They respect the rules and hierarchies. Rick’s neighbours, Sharon Tate and her husband, Roman Polanski (Rafal Zawierucha), live higher up in the canyon (at the end of a gated driveway) and also on the status pyramid. They are regarded not with envy or resentment, but with awe.

Tarantino’s sense of the movie past is often described as nostalgic. He tends to be seen—by admirers and critics alike—as a film geek, a fanboy, a fanatic cinephile with an encyclopaedic command of archaic styles and genres. True enough. But Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood shows that he deserves a loftier, possibly more contentious label. It’s the expression of a sensibility that is profoundly and passionately conservative.

John Ford, one of old Hollywood’s greatest conservatives, ended one of his greatest movies with the exhortation to “print the legend.” Tarantino’s answer is to film the fairy tale.

Alongside the knight and his squire, there is a princess —Tate—who lives in something like a castle and is married to a man who looks a little like a frog. Tarantino has never been much interested in sex or romance—violence and vengeance are what makes his stories run—but he has a sentimental investment in marriage and a thing about wives.

Sharon, who is barefoot, pregnant or both in most of her scenes, is not so much a symbol of innocence or glamour as an emblem of normalcy. The best stretch of the movie follows her, Cliff and Rick through their separate routines on a single day.

In the real world, six months after that magically ordinary imaginary day, Tate was murdered in her home on Cielo Drive, along with four of her friends. The killers lived at the Spahn Ranch, and were disciples of a failed musician named Charles Manson.

That’s the opposite of a spoiler, by the way. If you don’t know about the Manson family, or if you’re vague on the details of their crimes, you may not feel the tingle of foreboding that is crucial to Tarantino’s revisionism. Didion, in The White Album, wrote that “many people I know in Los Angeles believe that the Sixties ended abruptly on Aug. 9, 1969, ended at exactly the moment when word of the murders on Cielo Drive traveled like brush fire through the community.” But what if the ’60s never ended? Or rather, what if the ’60s, as a half-century of pop-culture habit has taught us to remember them, never really happened?

© 2019 The New York Times