BENGALURU: Loot and plunder have been an accepted part of warfare and the victor’s spoils. From times immemorial the victor has looted the property and treasures of the vanquished. Homer has recorded the destruction and looting of the rich kingdom of Troy by the barbaric Greeks. When Romans finally defeated rich Carthage, they carried back their statues and sculptures. Alexander the Great took treasures from fabulous Persepolis before setting it on fire. To this day Iranians/Persians lament this. Romans were faithful followers of the policy. They not only brought home treasures; they also brought back human beings in chains. And in poetic justice when the Vandals and Goths descended upon Rome, they did the same. Medieval times continued the policy in Asia, Europe and Africa with more or less the same barbarity.

The tradition of colonial plunder of art treasures and antiquities began with Napoleon Bonaparte during his Egyptian campaign. Standing before the great pyramids of Gizeh, he told his army, “Three thousand years of history look down upon you.” Soon after French officers and scholars entered and explored the great pyramids and were stupefied by the treasures they saw. Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign ended in defeat but his officers loaded the ships with ancient artefacts, including the Rosetta Stone. By the law of unintended consequences this is how the science of Egyptology began. The French emperor also took from Italy immortal art treasures, many of which like Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa remained in France despite repeated attempts of unified Italy to retrieve them. Belgium looted her African colonies and France of her North African and East Asia colonies, of artistic treasures on a scale that can be called criminal. Angkor Wat was saved by the tropical jungles that mercifully encircled this massive and exquisite temple complex.

In the heyday of Mughal rule of India (16th, 17th centuries), the country was an affluent and successful exporter of finished goods such as silk, textiles, ivory work, wooden goods, etc. It controlled one-sixth of world trade during the time of Emperor Shah Jahan. When the Mughal Empire weakened, European traders became more assertive in their demands for commercial concessions.

The East India Company strengthened its foothold in India during the 1770s after the battles of Plassey and Buxar. British political power was established in North India. Commercialization of agriculture spelt disaster. Rice fields were converted into indigo plantations as this product was in high demand in Europe. This resulted in decline in food production, resultant severe food shortage, culminating in decimating famines and demographic disasters. Governor General Cornwallis’ Permanent Settlement added to the crisis in rural India.

The commercial plunder of India began. They purchased these raw materials at abysmally low prices and sent them to Britain where the Lancashire and Yorkshire mills made cotton and silk goods. These were then returned to India as finished products which were forced upon the people. Saltpetre used for making cannon balls was garnered on large scale. These cannon balls would help in Britain’s wars in Europe and would be used against Indians.

Accompanying this economic looting was another plunder. India’s treasure trove of gold and precious stones was known throughout the world. Its craftsmen, artists and artisans were no less renowned. In fact India’s wealth and treasures were also its doom because this invited plunderers. The British Raj took great treasures such as the fabulous Kohinoor diamond, Tipu Sultan’s ring, Emperor Shah Jahan’s wine cup and many others treasures

But there is another aspect of British rule that merits mention.

Britain’s discovery of India is an episode of schizophrenia. Warren Hastings was an imperialist par excellence. While annexing kingdom after another, while splitting possible alliances against him, he also became an admirer of Indian civilization. He gathered a band of dedicated Indologists like Sir William Jones who delved deep into Sanskrit literature, both secular and religious. Sir William translated Kalidasa’s Shakuntala and completed translating Manu Samhita as he lay dying untimely in Calcutta. Hastings established the famous Asiatic Society in 1784 which began housing ancient Indian manuscripts and paintings. He asked the Board of Directors of the East India Company to commission Charles Wilkins to translate the Bhagavad Gita into English because it is he wrote, “the greatest and most profound work of religious literature of the world.” This is how the grandeur of Hinduism was introduced to the West. The Indian Museum in Calcutta was established in 1814 to house the sculptures that were being collected and excavated by British archaeologists. It became a material and cultural narrative of Indian civilization. When discovered by a young army officer of the Company, British archaeologists began restoring the caves of Ajanta and Ellora. Finally in 1861, Sir Alexander Cunningham, military engineer and scholar established the Archaeological Survey of India, which began restoration of monuments and excavation of ancient sites. Under the direction of Lord Curzon, a fervent imperialist, the Ancient Monuments Act, (1908) and Antiquities Act (1908) were promulgated—to protect Indian heritage.

The British Museum in London houses cultural remains of many civilizations of many eras. These are well preserved, classified and protected. This museum provides material for research and historical information. Indian antiquities are safe here for now and for posterity. Many museums in the West house paintings and antiquities of other nations, not necessarily of their former colonies. Art masterpieces have been sold, purchased, auctioned and transported from one state to another. Volumes could be written on the history and provenance of these treasures.

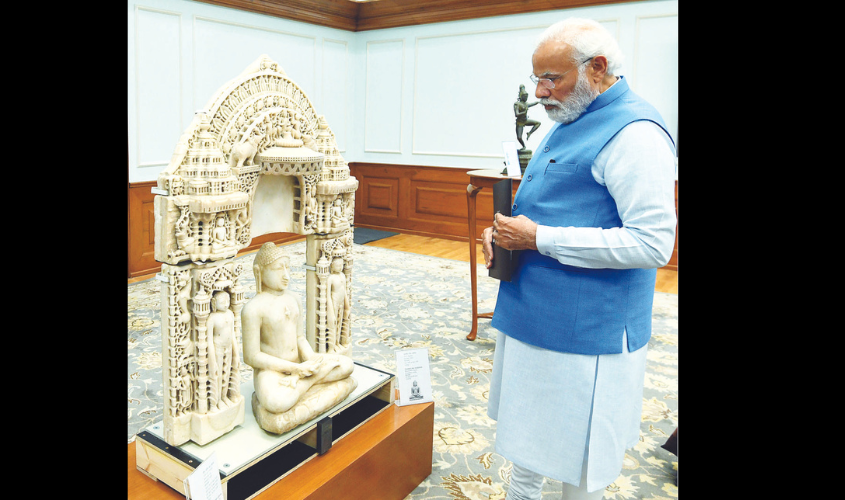

However every country has a right to ask for restitution of art treasures taken by force during colonial rule—as indeed they are now doing. But this also requires dedication on the part of the legatees of national cultural heritage.

During my tenure as Director General, Archaeological Survey of India, I came to know of removal of treasures from temples. Chola bronze statues surfaced in Western cities in the 1970s and 1980s. Excavation reports have not been written or published because that would entail having to record and display the antiquities found. Powerful bureaucrats have wrenched out statues (dating from 5th century to 18th century) from museums in their bailiwicks and have tried to send them abroad. During militancy in Jammu-Kashmir one enterprising archaeologist managed to smuggle out the last of Kushan era artefacts of Harwan which went to Pakistan en route to the West. And then there are the cocktail party circuit aficionados of antiquity who have cosy contacts with people in the antiquity trade. A Pallava era Ganesh, a carved door from Amber fort, inlaid Mughal tables, not only embellish elegant drawing rooms but serve as status symbols like the latest BMW car.

If the vast cultural treasures of India are returned, both the Central and State governments will have to build huge museums to house them, employ many more scholars and archaeologists to classify and record them, masons and artisans to restore them to their pristine status. Many more archaeological engineers, archaeological chemists, even epigraphists would be required. Security would have to be augmented with necessary equipment. Archaeological departments at present function below their capacity due to paucity of fund and staff. To rectify these deficiencies huge financial allocations are imperative.

If the treasure trove is returned, there must be guarantees that these will remain in absolute security. There must be people who guard the guardians of the nation’s heritage.

*Achala Moulik is a former Education Secretary, Government of India, and former Director General, Archaeological Survey of India.

House them well: Return of Indian artefacts

- Advertisement -