I have been re-reading Rajmohan Gandhi’s biography of his maternal grandfather, Chakravarty Rajagopalachari.

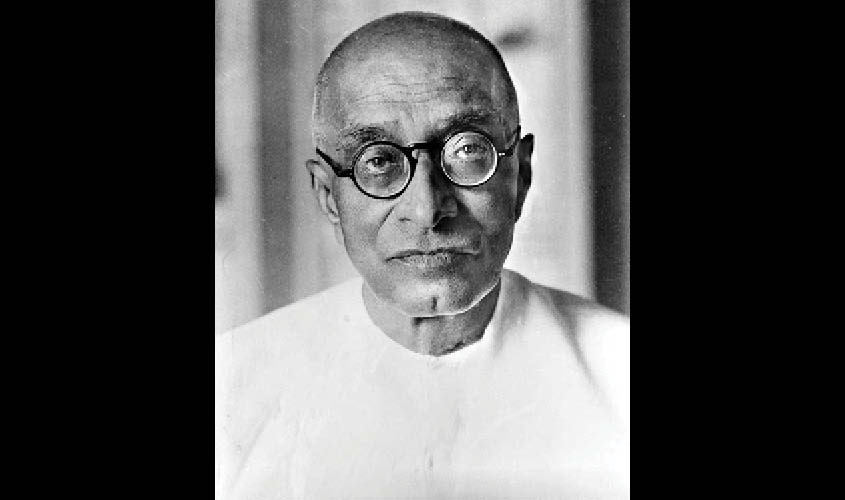

His name consisted of 26 letters. Mahatma Gandhi reduced it to six letters—Rajaji. He was one among five of Gandhi’s closest chelas. The others were, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Jawaharlal Nehru, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, Rajendra Prasad. With the exception of Azad, the others had been lawyers. (Nehru never became a serious practising lawyer.)

Rajaji was born in 1878 in a poor Tamil Family in a village in South India called Thorapalli. His family were Iyengar Brahamins. Rajaji was Premier of Madras Presidency from 1937 to 1939. He was Home Minister, Governor of West Bengal and finally Governor-General of India. He died in Chennai in December 1972, at the age of 94.

He was in his mid-80s when I got to know him. He did not have a commanding presence, but his intellect was of the highest quality. He was arguably among the three outstanding intellectuals to come out of the Congress. The other two were Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Gopal Krishna Gokhale. Jawaharlal Nehru was an A-minus intellectual.

Rajaji arrived in New York in October 1962, leading the Gandhi Peace Foundation delegation to press for a total ban on nuclear test. While in New York, he stayed in my two-bedroom apartment along with R.R. Diwakar, who had been a minister in Nehru’s cabinet for a short while. I shifted to a colleague’s apartment. Nevertheless, I met him several times a day.

He spent an hour with President Kennedy at the White House. The President was much impressed. A fascinating account of this encounter is given in B.K. Nehru’s autobiography, Good Guys Come Second.

Here I reproduce brief portions of the conversations I had with Rajaji. I, to my delight, soon realised that he rather liked having me around. I kept a record of our conversations.

***

October 9, 1962.

Rajaji in a relaxed and communicative mood. I implore him to write the autobiography or dictate his reminiscences.

Rajaji : I know we have no sense of history, but does that really matter in the ultimate sense? After all, we do not know what Kalidas said to anyone. What he did and what he wrote is important.

Natwar: If everyone took that view there would be no history. You have played such an active, at times decisive though controversial role, in recent Indian history that you owe it to the nation to leave behind your account of what happened. After all, Gandhiji and Pandit Nehru wrote autobiographies.

Rajaji: Well, I had no time.

Natwar: Presumably, your modesty prevents you from writing.

Rajaji: No. I am not modest that way. I really have had no time. I keep myself busy in so many ways.

Natwar: You must have had plenty of time when you were Governor-General.

Rajaji (smiling): Yes! I did. But all the time was taken up in patching up daily quarrels between the Prime Minister and the Deputy Prime Minister. Pt. Nehru wanted me to continue in Delhi. The rest is well-known.

Natwar: In 1953, I was Secretary of the Indian Majlis at Cambridge and invited Lord Pethick-Lawrence to address the Majlis. Later I asked him, “Which Indian leader impressed you the most?” And without hesitation he named you.

Rajaji: Did he? I am glad to hear that. He was an excellent man. He wrote to me explaining why he had married again. Cripps was a very impressive man but in the Cabinet Mission he played number two to Pethick-Lawrence. When did you meet Pethick-Lawrence?

Natwar: 1953.

Rajaji: Long after the Cabinet Mission.

The conversation then turned to the Partition of India. To provoke him, I said, “Lord Mountbatten sold Partition to Panditji and Sardar Patel”.

Rajaji: Now, let me tell you Natwar Singh, I sold Partition to Mountbatten. The Attlee Government had already made up its mind in that direction but did not know how to put it across in a concrete manner. I said Partition was the only answer. He first talked to Nehru and then to Patel. They both had seen what was going on and accepted reality.

Natwar: But Gandhiji was against it and he held out till the very end. Why did he suddenly give in? It came as a great shock even to the young like me.

Rajaji: Gandhiji was a very great man but he, too, saw what was going on. He was a very disillusioned man. When he realised that we all accepted Partition, he said, “If you all agree, I will go along with you.” And after that he left Delhi.

***

October 10, 1962.

Rajaji: You should have come with me to the Columbia University meeting. The boys and girls were very intelligent and asked meaningful questions as to what dharma is and what karma is. I told them dharma was universal duty plus natural order. They said, then it was socialism. I said, “Yes, if it was voluntary, but not the Indian Government’s socialism.” It was not a public meeting, so I said it. I do not want to do anything to embarrass you or the Government here.

***

I left New York in May 1966 and joined the Prime Minister’s office. I kept in touch with Rajaji. He wrote to me on November 24, 1966, “I am not surprised you so much like the service under Smt. Indira Gandhi. She is splendidly endowed with all the graces of a good civilised lady. She grew up under the example of her gracious father…”