India’s innovation story is by now well documented. The country’s rise from 81st place in 2015 to 40th in the World Intellectual Property Organization’s Global Innovation Index 2023 is not accidental. Patent filings now exceed 66,000 annually, with a steadily growing share of resident applications. These gains reflect years of policy reform, entrepreneurial drive and the gradual strengthening of a research ecosystem.

And yet, even as India builds technological capability, a crucial gap persists: the gap between achievement and assurance. At a moment when the country is still consolidating its scientific credibility, trust becomes indispensable. Every public claim carries weight beyond its immediate context.

It is precisely for this reason that moments of premature celebration are so revealing. The recent controversy at an AI summit in Delhi, where a university’s claims about the development of a showcased robot were later revised, was not merely a minor embarrassment. It offered a window into deeper questions about verification, institutional responsibility and the intellectual seriousness required of a nation that seeks to position itself as a global technological power.

The factual correction was not the most troubling element. Mistakes happen. What was far more disquieting was how responsibility was framed afterward. Reports suggested that senior leadership distanced itself from the statements of a single faculty member. Such distancing may be administratively convenient, but it raises a fundamental governance question. Contemporary understandings of accountability extend beyond what leaders explicitly know to what they ought reasonably to have known. Institutions are responsible not only for avoiding misstatements, but for building systems that prevent misrepresentation in the first place.

Events attended by national and international dignitaries are not spontaneous performances. They are curated environments shaped by preparation, vetting and oversight. If an inaccurate claim is made within the scope of employment, responsibility cannot be confined to an individual. If the claim exceeded authority, institutions must explain how safeguards failed. Universities cannot function as neutral stages from which statements accidentally emerge. Governance is systemic; when systems falter, responsibility cannot simply be pushed downward.

When individuals alone are made to bear the weight of institutional lapses, oversight is not strengthened. Scapegoats are created. These concerns are not hypothetical. Recent years have seen allegations of plagiarism involving well known economists and policy advisors. In several instances, explanations pointed to oversight or the complexities of collaborative drafting. It is entirely plausible that such episodes did not reflect deliberate misconduct. But that is precisely why institutional response matters.

An apology, however sincere, is not the same as accountability. An apology is procedural. Accountability requires investigation, review, clarity and, where warranted, consequence. Without viable process, the public is left with ambiguity.

When allegations arise and institutions respond with silence, opacity or mere correction, a quiet message is sent. It suggests that reputational management may suffice. It implies that intellectual standards can bend at higher levels of influence. Over time, such impressions corrode seriousness. They teach younger scholars that visibility may outweigh verification. They signal that correction can substitute for scrutiny.

The goal is not to vilify individuals but to insist that intellectual integrity must be treated as foundational. If oversight occurred, it should be examined transparently. Processes must apply uniformly. Otherwise, apology becomes a way to replace rather than initiate accountability. These concerns become even more urgent as India opens its doors to foreign universities. International academic partnerships do not operate in abstraction. They function within a framework of shared norms, compliance structures and reputational trust. Academic integrity is not an optional virtue in this context; it is currency. It is the construct within which joint research, faculty exchange, degree recognition and institutional collaboration operate. In many Western academic systems, norms governing plagiarism, research misconduct and public office ethics are enforced with visible seriousness. Institutional inquiries are formal and documented. Consequences follow process. Resignations sometimes occur not only upon proven wrongdoing but upon credible doubt, in order to protect institutional credibility. Whether one agrees with each instance is secondary. The underlying principle is clear: integrity is non-negotiable. Foreign universities establishing campuses in India are not merely expanding markets. They are extending decades, sometimes centuries, of accumulated reputational capital into a new jurisdiction. They are trading on trust painstakingly built over generations. Any perception that local standards are elastic, or that accountability is inconsistent, introduces reputational risk that cannot be dismissed lightly.

If India seeks to be a credible partner in the global knowledge architecture, it must demonstrate that academic integrity is systemic, not episodic. Oversight must be robust. Investigations must be transparent. Standards must be enforced irrespective of status. Ethical seriousness cannot be intermittent.

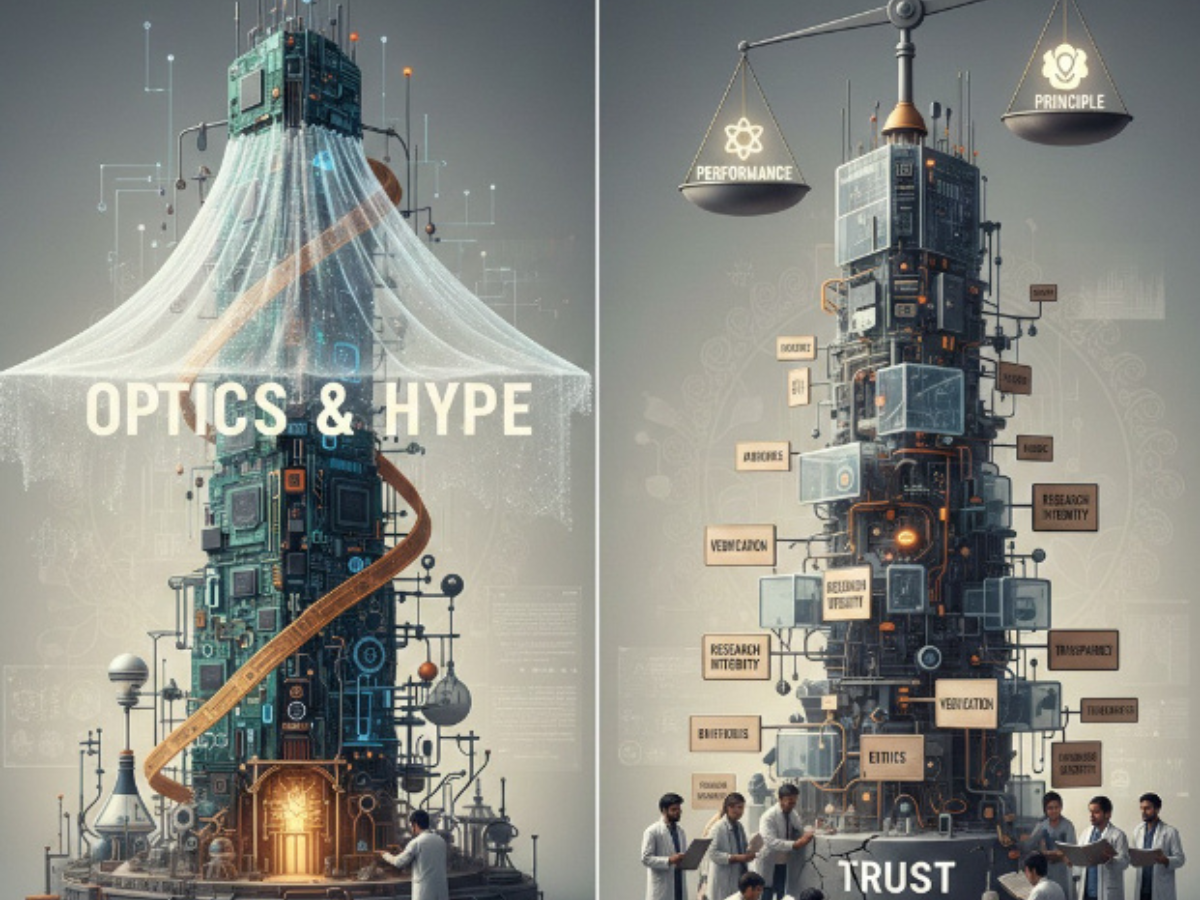

It must be institutionalised. Beyond academia, a broader cultural shift is visible. Increasingly, optics are mistaken not merely for proof, but for performance itself. Announcement becomes achievement. Visibility becomes validation. Presence substitutes for progress. The pressure is not simply to perform; it is to appear to perform. Optics create the illusion of movement. They generate the impression of innovation without the sustained labour that genuine innovation demands.

In such an environment, incentives distort. Universities respond to visibility metrics. Faculty are encouraged to cultivate digital presence. Public events become stages.

The symbolic act of unveiling can overshadow the material act of building. This is not merely a communication problem. It is a structural one. When appearance is rewarded more reliably than substance, seriousness weakens. If optics suffice to signal competence, the discipline of performance erodes. And if performance erodes, proof becomes irrelevant. Scholarship cannot survive in such an ecosystem. Digital tools can manufacture polish and enhance presentation, but they cannot manufacture depth. Integrity and rigour are not ornamental virtues. They are structural necessities. Without them, the centre of scholarship collapses. When a university’s credibility falters, the damage does not stop with administrators or faculty. Students carry institutional reputation into classrooms, laboratories, courts and workplaces. When standards appear compromised, students pay the invisible price of doubt. Indian academicians stand at an inflection point. It possesses talent, ambition and expanding global engagement. What it must now decide is whether to anchor this ambition in meritocracy, rigour and ethical consistency, or allow it to drift toward media hype and momentary visibility.

Technology can create spectacle, but it is integrity creates stature. Innovation without integrity is a structure without foundation. It may rise quickly and draw applause, but it stands on hollow ground, a house of cards built on performance rather than principle.

It has shape, but no spine. If India wishes to build institutions that command global respect rather than fleeting attention, it must choose depth over display, verification over velocity and merit over marketing.

Institutions are not ultimately judged by how loudly they announce achievement, but by how consistently they uphold standards. And once standards erode, they are far harder to rebuild than reputation.

*Dr Neeti Shikha is Senior Lecturer in Law and Programme Leader for the Online LLM at Bristol Law School, University of the West of England, UK. The views expressed are personal.