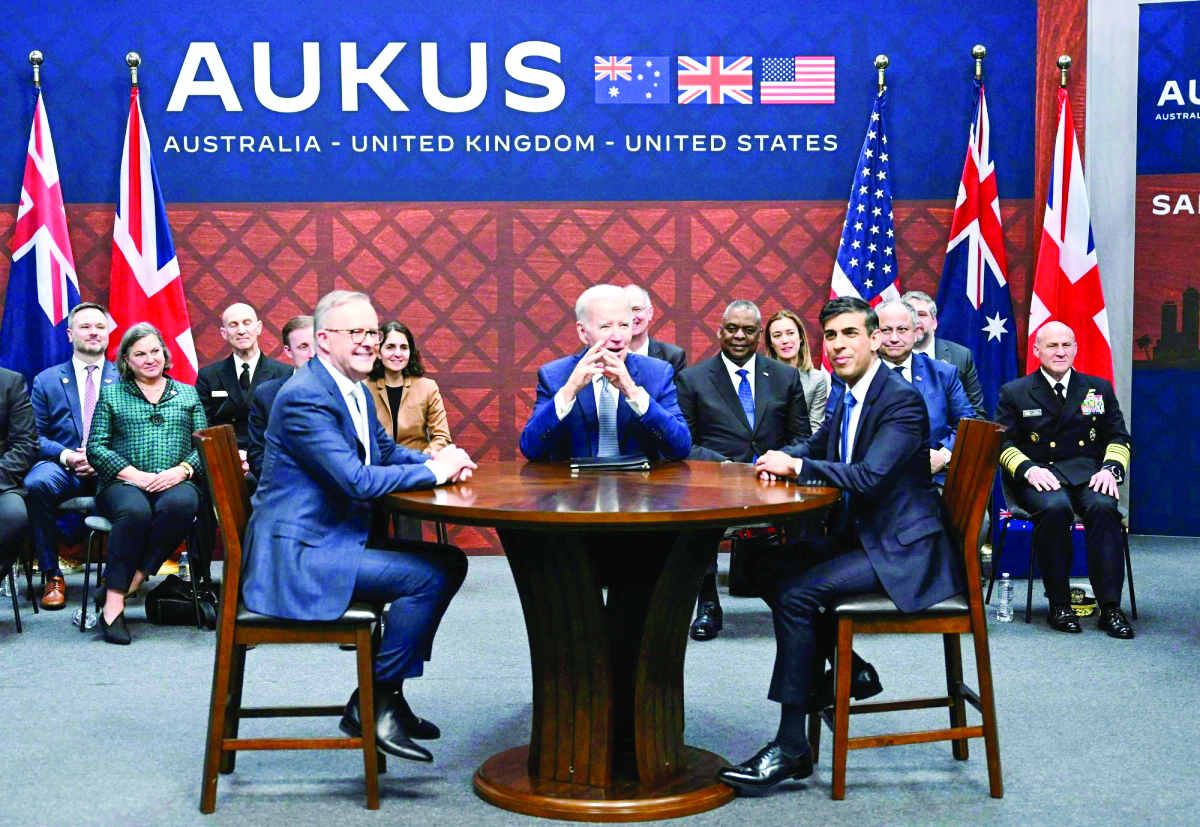

LONDON: It’s now nearly four years since the trilateral security pact between Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States, known as AUKUS, was announced to a great fanfare. The fundamental principle of the pact is to strengthen defence ties between the three nations and in doing so enhance security in the Indo-Pacific region. The three countries already had a history of military and intelligence cooperation as members of the “five eyes”. But rising tensions in the Indo-Pacific resulting from China’s expansive territorial claims in the South China Sea, its military modernisation and growing economic and military clout prompted the three nations to look for new ways to bolster security in the region.

The centrepiece of the deal, announced on 15 September 2021, was a plan for the US and UK to help Australia acquire nuclear-powered submarines, which would mark a significant shift in Australia’s defence posture. By comparison with conventional submarines, the nuclear-powered variety are faster, more durable and capable of operating for longer periods without refuelling. They are also much quieter and harder to track, staying submerged for months and able to travel vast distances without surfacing. Once acquired, Australia will be able to deploy its new submarines across the -Pacific, into the Indian Ocean, South China Sea, or even the Middle East if needed. The result is that a potential adversary, such as China, must assume that an Australian sub could be anywhere, creating uncertainty and discouraging aggression.

As a result of AUKUS, Australian sailors and personnel are already training with the US Navy and Royal Navy to learn how to operate and maintain nuclear submarines. Many Australian officers are even currently embedded on US and UK nuclear submarines to gain hand-on experience. From as early as 2027, AUKUS partners will begin rotational deployments of nuclear submarines to HMAS Stirling, a naval base in Western Australia, a move designed to expand Australia’s infrastructure and operational readiness while increasing Western naval presence in the IndoPacific. The next step will be Australia’s purchase of at least three Virginia-class nuclear-powered submarines from the US in the early 2030s, with an option to purchase two more.

This will also initiate the development of a new class of nuclear-powered submarines, called SSN-AUKUS, which will be British-designed, use US combat systems and reactors, and will eventually be built in both Australia and the UK. Australia’s first locally built SSN-AUKUS, to be constructed in Adelaide, is expected in the early 2040s. In order to allay fears of nuclear proliferation, Washington made it clear from the outset that Australia will not acquire or host nuclear weapons as part of AUKUS. There will also be a limit on the technology transfer of nuclear propulsion systems, as the nuclear reac tors provided by the US and UK will likely be sealed units, not opened or fuelled by Australia. In the lead-up to Donald Trump’s second coming in the White House, many defence analysts had spent considerable time pouring over his thousands of hours of interviews and speeches in order to glean some clues on his attitude to the AUKUS programme which he inherited from Joe Biden.

There were serious concerns that he might seek to renegotiate the deal or perhaps alter the timelines. These anxieties were based on the likelihood that the US will have to temporarily downsize its own naval fleet as part of the agreement, something Trump may interpret as an affront to his “America First” ideology. Many hoped, however, that The Donald would see the project as an obvious, if unspoken, challenge to China and therefore accept the temporary reduction in the number of America’s nuclear submarines. When former UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson said in September 2021 that the AUKUS deal was “not intended to be adversarial towards China,” President Xi Jinping simply did not believe him. The Chinese leader replied that AUKUS would “undermine peace” and accused the Western nations of “stoking a Cold War mentality.”

There have been regular outbursts against AUKUS from Beijing, framing the pact as contravening international norms, and exacerbating tensions which risk sparking an arms race. Many observers find Beijing’s comments risible. In the past decade, China increased its military spending by 800 percent, the biggest military build-up in peacetime history. It now deploys more naval vessels than the US. In modernising its nuclear arsenal, China aims to reach close to parity with Russia and the US by the end of the decade, while all the time it flexes military muscle in places that have long been under the sole purview of the US. Set against this, the acquisition of a few AUKUS nuclearpowered submarines by Australia is hardly a major threat.

True to form the Trump administration launched a formal Pentagon review of this Biden initiative in mid-June this year, led by Undersecretary of Defence Elbridge Colby. It aims to ensure that the AUKUS agreement aligns with Trump’s “America First” policy and that US industrial and naval readiness are not compromised. Noises off-stage, however, suggest that the US naval leadership is warning that unless US shipbuilding doubles its current pace, Australia may not receive all the promised Virginia-class submarines starting in 2032. It appears that US production rates are currently well below what would be needed to fulfil both domestic and AUKUS requirements. There are also political and diplomatic issues which might affect the future of AUKUS.

Last month, a report in the Financial Times claimed that Colby had been privately pushing Australia for a pre-commitment to support the US in a future Taiwan Strait conflict. This had raised serious challenges for Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese who made it clear during the early AUKUS discussions that, while Australia hugely values its relationship with the US, Washington should not expect blanket support in confronting China. He insists that Australia will choose the level of any future involvement based on its national interests and the broader regional requirements.

Many observers see Colby’s private pressure having the broader imprimatur of the Trump administration. The optics of the overt linkage with Colby leading a snap Pentagon review of AUKUS cannot be lost on observers. Donald Trump’s fixation with US allies “paying their dues” has manifested in intense pressure on NATO countries to bolster defence spending. Some in the White House claim that this pressure has worked, with European countries now committed to significant growth in their defence budgets in the coming years. It now seems that it’s the turn of America’s IndoPacific allies to feel the heat from Washington.

There is no doubting that Australia remains firmly committed to AUKUS, having already paid $!.6 billion into the programme this year, with further contributions expected to strengthen US and UK industrial capacity. Last week, Britain agreed to a bilateral treaty with Australia, the “Geelong Treaty” called after the city where it was signed, which will underpin the two allies’ submarine programmes. This 50-year bilateral treaty provides continuity for submarine production even if the US commitments face delays, offering Australia a sovereign path towards building and sustaining its own SSN-AUKUS fleet by the early 2040s.

Colby’s review is expected to continue through SeptemberNovember 2025, but Washington stresses that it’s a strategic check rather than a withdrawal decision. So, while this review introduces uncertainty over timelines and deliverables, especially concerning submarine production, the structure and shared goals of AUKUS appear to remain intact, with concrete progress on training, infrastructure and treaties. Australia and the UK are doubling down on their commitments, even in the face of US industrial challenges. Unquestionably, AUKUS is alive and in good health— and will survive.

John Dobson is a former British diplomat, who also worked in UK Prime Minister John Major’s office between 1995 and 1998. He is currently a visiting fellow at the University of Plymouth.