Why India must export high-quality, assimilatory labour to combat global demographic crises and counter anti-India extremism abroad.

NEW DELHI: Consider the following. There are approximately 220,000 Sikhs in Italy. One of the proudest achievements of the community that immigrated from India is saving parmesan cheese through their hard work and sustainable farming practices. In the UK, there are about 500,000 Sikhs, while in Canada, the number is approximately 750,000. In the US and in Australia, the Sikh community numbers around 250,000, and 200,000 respectively.

The question to ask is why is Khalistani extremism, a subset of the Sikh population in these countries, so aggressive in Canada, in the UK, the US, and even in pockets of Australia, while it is relatively subdued in Italy? The three answers of this question are clear—in Italy, unlike in other countries, the Khalistani groups have much less access to local political support. In Italy, the Khalistani groups have also not yet managed to create a united front with Islamist organisations, many of them with connections to the Muslim Brotherhood, and Pakistan’s notorious secret service, the ISI. Third, in Italy, where Hinduism is one of the fastest growing faiths, the onground pushback is much stronger to Khalistani shenanigans. There is a moral in this story—the world needs “better quality” immigration.

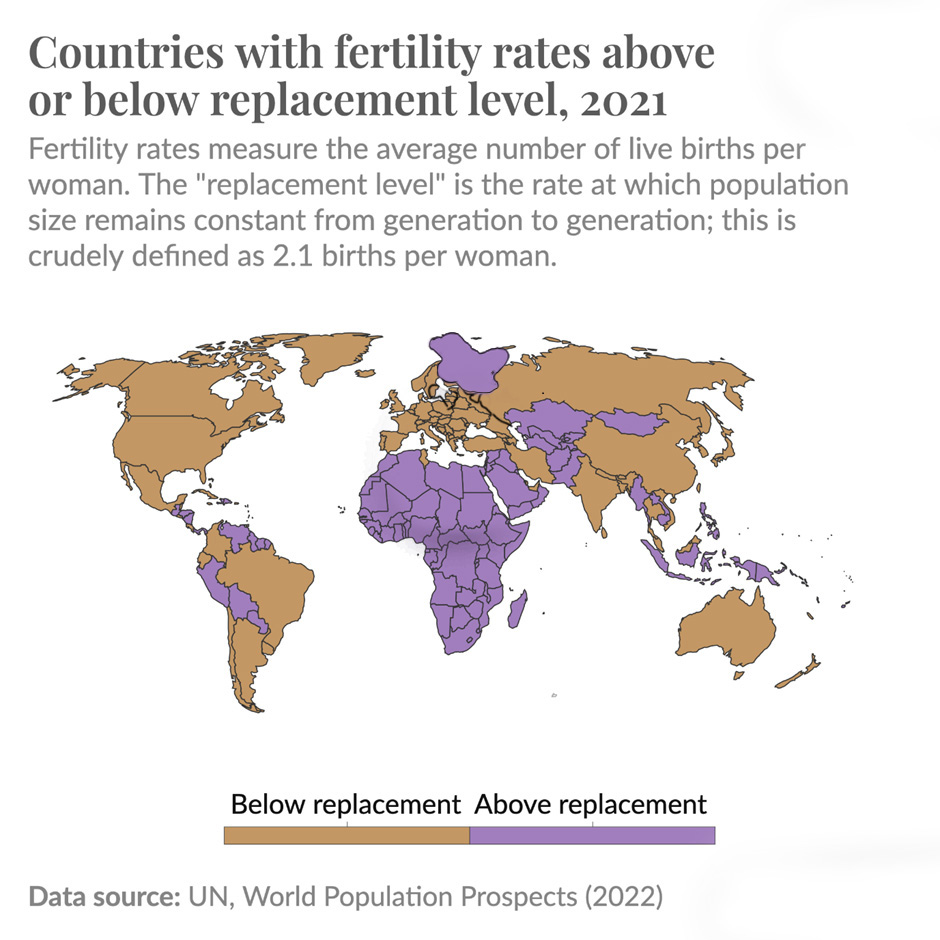

Across the globe, some of the richest countries in the world cannot remain rich or prosperous in the next two-five decades. The chart with this article shows the extent of the crisis. And even though India too is already below replacement rate, it still has a lot of labour to spare, especially from states like Bihar and Uttar Pradesh which are still producing many, many babies. But this urgent demand now faces tremendous backlash as in the last decade many of these countries, especially in Europe, have taken in vast numbers of people without thinking through a solid integration plan. So, what anyone could have predicted—but what these countries were wilfully blind to—has unfolded.

A massive crisis of integration that has turned some of the safest places in the world very unsafe—consider that Malmo in Sweden is now notorious for gang wars and bomb explosions. In fact, the situation has been so bad in Sweden that in neighbouring Denmark, Norway and Finland, they even have a term for it, the “Swedish condition”. From Germany to Sweden, from America to England, efforts are on to reverse the tidal wave of illegal (and legal) immigration even as these countries grapple with the issue of integration and mass subversion of their democratic structures. Time was when the fear was the slipping in for extremist who would conduct terror attacks, or radicalise some youth.

Things are much worse today as countries are faced with demographic change in cities and towns, followed by active political manoeuvring to change election outcomes, and get people into public office who could, and would, change the very laws. It is this kind of political pressure due to demographic change in many constituencies which has been the reason for a shroud of silence on the decades-long grooming gang issue of kidnapping and gang rape in the UK, where the perpetrators were mostly Pakistani men, and yet there was deep political and civic collusion to prevent police action on the criminals.

The Baroness Casey report in the UK has revealed the depth of this pressure and resulting collusion especially between Labour Party MPs and communities shielding the assailants including MPs blocking a national enquiry in the matter three times. This is the debate that is happening in the UK on soto voce insertion of sharia especially into laws and rules at the council level also shows the kind of integration problems that countries which were hitherto assumed to be wellassimilated also face. So, this then is the conundrum—there is tremendous demand for assimilatory immigration but great resistance to immigration waves as they exist at the moment. Could India bridge the gap? Yes, it can, and indeed, it must. India must now reimagine the expansion of its diaspora as a “global public good”—providing trained and talented workforces around the world who are also highly assimilatory. Japan, for instance, is a country that acutely needs assimilatory labour in all areas, from healthcare to technology. Japanese companies gave their biggest average pay raise in 34 years in July 2025, which was also the third consecutive year where significant raises had been offered, and by 2035, Japan’s labour shortage by some estimates could be nearly four million people.

All research shows that the many shared social and cultural norms and values between India and Japan make Indians a good fit for immigration into Japan where migrants now mostly come from China and Vietnam and where instances of radicalism already led to the Japanese Supreme Court allowing surveillance of Muslim immigrants in 2016. Since then, such concerns have greatly heightened. Japanese organisations often talk about skilled immigrants from India as a lowhanging area of cooperation which deserves a lot more attention. Could Indian policy create nudges that enable greater talented and hard-working immigration to Japan? Could we create programmes that would encourage Indians to learn Japanese, understand Japanese business and work culture? Other countries that could be key are Russia, Israel, South Korea, Germany, France, Italy and Sweden, and the Middle East.

In each of these cases, there is a population problem, and in many there is also an immigration problem. Excessive non-assimilatory migration is perhaps today the EU’s biggest challenge, even as it is trying hard to contain the problem, but it might be a case of shutting the stable doors after the horses have bolted. The only correction that can be done is demographic balancing using assimilatory immigration which could help them maintain their prosperity—without destroying their society and culture. Russia, for instance, has announced that it is looking to take in up to a million Indians in 2025 to make up for its depletion in the war with Ukraine. In countries like Germany and France, for instance, without an urgent focus on assimilatory immigration, both economic and social turmoil loom large. South Korea and Italy face crisis level demographics and need to boost working populations. To such countries, talented Indian migration is a relatively easy fix. Indian workers—at all levels, from the corner office to the factory floor, from hospitality to homes—could address, swiftly, many areas which have a demographic crisis. Investing in supplying this labour force—especially since so many Indians are trying, many illegally, to find work outside the country—to these countries in a procedural manner could be a diplomatic and economic win.

We must see this supply as part of India’s contribution to global public goods in the years to come as demographics becomes—or threatens to become—destiny for many nations. It is not often understood that while India has the biggest overseas diaspora, its rate of emigration (the proportion of its birth population living abroad) is still quite small—only 1% compared to the global average of 3% and lower than even the US. Therefore, there is immense scope of utilising this route as a developmental and strategic mission. That a well-performing diaspora brings benefits like remittances, and creating skills exchanges almost like a human bridge are obvious but there is a deeper issue to consider. As the Mirpuri migrants from Pakistan in the UK have shown, and I shall write in detail about this issue in a future essay but for now suffice it to say, relatively small but highly organised and politically active immigrant populations especially from Pakistan and Bangladesh can do considerable damage to India diplomatically by continuously building political and street antagonism towards it. This has been seen again and again with the reactions in the UK, Canada and in other places to Indian domestic policy making like the those aimed at agrarian reform or weeding out illegal migration and others. These groups, as they grow larger, use political and legal processes to target India and Indian politicians who work to protect the country’s sovereignty.

They become malignant pressure groups in the local politics of the host country, and start to adversely influence media and academia against India’s interests. Pakistan, more and more backed by China, especially has used its immigrant populations relentlessly as a propaganda force against India—including in recruiting Indian turncoats and placing them in propaganda front organisations in the name of human rights but, in reality, completely devoted to using every means to counter India’s domestic policy-making and drain consensus on key strategic targets of the country. This is usually countered by Indian diplomacy, but this needs deeper more resilient action. It must be understood, to cite an example, that Khalistani radicals in Australia are able to, at the moment at least, create less trouble for India in that country because the local government is not sold out to these pressure groups—and, critically, there is a vibrant and vocal Indian community, notably from Haryana, which powerfully pushes back against the machinations of the Khalistanis.

The Indians in Australia are well-integrated, one of the most educated and economically wealthy, communities in the country, and they are also wellorganised and willing to pushback against malicious propaganda against the mother country. They have consistently shown that they are loyal and highly contributing citizens of the host country but not shy of speaking up for the parent nation. Unlike in the UK, there isn’t—yet—the kind of vicious political action among malevolent groups ganged up against India in Australia as seen in the toxic combination of Khalistanis and Islamists in Britain. This cannot only be countered via diplomacy, as critical as that is. It needs to be responded to in the media, and on the streets, and there is no group who can do it better than Indians who usually among the most successful migrant group in every country where they exist. It is time that India considers thinking of Indian immigrants as a vital part of our national— and strategic—narrative.

Hindol Sengupta is professor of international relations at O. P. Jindal Global University.