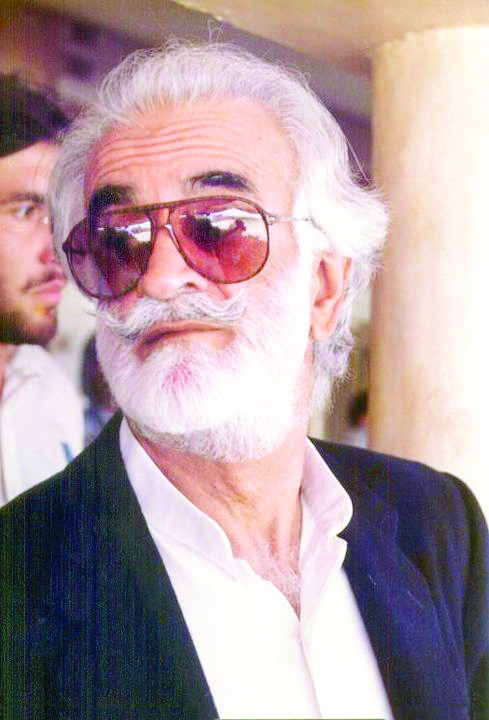

NEW DELHI: The mountains around Kohlu in Balochistan are a hard place to hide. Jagged cliffs cast deep shadows across dry riverbeds, and the heat in August clings like a second skin. On the afternoon of August 26, 2006, those cliffs carried the echo of gunfire. Inside a narrow cave, Nawab Akbar Khan Bugti—former governor and former chief minister of Balochistan, and the chief of the Bugti tribe—was making his final stand. The hideout, located inside a cave in the Chalgri area of the Bhambhoor hills, was shelled and bombed by the military. Bugti’s death was a result of intense bombardment and crossfire between his men and troops.

Approximately 21 security personnel and dozens of Bugti’s aides and followers were also killed during this operation. However, there have been attempts to skew the fact, with claims that the cave collapsed due to an explosion of undetermined origin during what was described as a negotiation attempt by the military. That explanation has largely been seen as narrative control by the Pakistani security establishment. When the dust from the firing cleared, Bugti was dead, along with several of his companions.

For President Pervez Musharraf ’s government, it was presented as a decisive victory against a “rebel chieftain.” For many in Balochistan, it was the death of a leader who had refused to yield on demands for greater autonomy—and the beginning of the province’s most enduring insurgent phase.

Bugti’s political career was as complicated as the province he led. Educated in Lahore and Oxford, fluent in both the language of the tribes and the language of Islamabad, he had served as interior minister, as governor, and as chief minister. He could be combative—breaking alliances, switching sides—but his positions on Baloch control over resources rarely wavered.

In the months before his death, he was in open conflict with the central government over gas royalties, troop deployments, and the rights of Balochistan’s people. Military operations intensified in and around his stronghold. The final assault at Kohlu was swift, and his burial was under tight security, away from the crowds who wanted to honour him.

Historians and security analysts date the modern Baloch insurgency in “waves.” The first flared soon after Pakistan’s creation; the second and third in the 1950s and 1970s. Bugti’s killing ignited the fourth wave. What distinguished it was scale and composition. Armed groups such as the Baloch Liberation Army (BLA) and the Baloch Liberation Front (BLF) escalated attacks on security forces, pipelines, and railways. Protests spread to urban centres. A younger, more educated generation, angered by accounts of enforced disappearances and heavyhanded security sweeps, began to join the cause.

Pakistan’s military response was to double down. Troop numbers in the province increased. Intelligence operations intensified. The narrative from Islamabad emphasised “law and order” and, increasingly, foreign interference.

Nearly 20 years later, the fourth wave is still in motion. The targets have shifted—from lone outposts to coordinated, province-wide strikes like July 2025’s Operation Baam—but the grievances have not. Balochistan remains Pakistan’s largest but least developed province. It’s natural gas fuels other regions, but locals complain of inadequate infrastructure, underfunded schools, and poor healthcare.

Resource projects, from gas fields to the port at Gwadar, are touted as engines of prosperity, but critics say they enrich outsiders and militarise the province further. Security monitors reported that separatist incidents nearly doubled in 2024 compared with the previous year. Attacks in 2025 have included the hijacking of the Jaffar Express, bombings in Khuzdar, and sabotage of telecom networks.

In this environment, new leaders have emerged— not all of them carrying rifles. Dr. Mahrang Baloch, a 30-year-old medical graduate, has become one of the most prominent civilian figures. As an organiser with the Baloch Yakjehti Committee, she has led long marches and sit-ins calling for the return of the disappeared. Her arrest during protests in March 2025 drew international condemnation; her nomination for the Nobel Peace Prize that year also signalled the movement’s widening recognition. Women’s participation in protests is more visible than in past waves, reflecting both the breadth of discontent and the determination of families whose fathers, brothers, or sons have vanished.

At demonstrations in Quetta, Gwadar, and Turbat, women hold up photographs of missing relatives, some gone for over a decade. The Manufactured Narrative From the earliest days of the fourth wave, Pakistan’s military establishment has promoted the line that unrest in Balochistan is fuelled externally rather than rooted in local discontent. What began as an insinuation has since been codified into official dogma. In 2025, the Ministry of Interior went as far as designating certain Baloch militant groups as “Fitnaal-Hindustan”—a phrase crafted to brand them as Indian-controlled proxies. This framing serves a deliberate purpose. By alleging Indian training, funding, and direction, Islamabad seeks to deflect responsibility and delegitimise the movement as foreign-engineered. Yet, no international body, foreign government, or independent investigator has ever substantiated these claims.

Rights groups point instead to systemic abuses— enforced disappearances, extrajudicial killings, and economic neglect—as the true drivers of the resistance. Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and even Pakistan’s own Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances have documented thousands of missing-person cases since 2011. For critics, the “India hand” narrative is less a reflection of fact than a tool of perception management—one that absolves Pakistan’s state apparatus while obscuring the grievances that continue to fuel defiance in Balochistan.

The state’s security measures have sometimes swept far beyond militant targets. In August 2025, authorities suspended mobile-data ser vices across Balochistan for three weeks, citing the need to disrupt insurgent coordination. Businesses ground to a halt; students missed online classes; families lost contact with relatives abroad. Earlier in the year, after the Jaffar Express hijacking left at least 31 people dead, security forces launched sweeping raids. Once again, officials pointed to “Fitna-al-Hindustan.” Once again, no evidence was made public.

Maj Gen R.P.S. Bhadauria (Retd) is the Additional Director General of the Centre for Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS), New Delhi, and was formerly the Director of the Centre for Strategic Studies & Simulation (CS3) at USI of India, having served in the Indian Army for 36 years.