Pakistan long dominated Indian nuclear thinking. That should be no surprise. Pakistani Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto reportedly wrote, “There’s a Hindu bomb, a Jewish bomb and a Christian bomb. There must be an Islamic bomb.” After India’s 1974 nuclear test, he declared, “We will eat leaves and grass, even go hungry, but we will get one of our own.” India had every reason to develop a nuclear weapon, especially with an expansionist China on its borders, already occupying a 38,000 square kilometre chunk of Ladakh.

The nuclear arms race between India and Pakistan grew acute after Pakistan tested its own nuclear weapon in 1998. One of the major international concerns surrounding the Kargil crisis the following year was the immaturity of Pakistan’s nuclear doctrine: It is one thing to possess the world’s deadliest weaponry; it is another to have command and control over their use. The fear in both Washington and Beijing at the time was that a Pakistani general angered by the loss of his lieutenant could set off a cascade that would end with a nuclear detonation in Delhi or Mumbai. The radicalism of Pakistani society remains a major concern. During my first trip to Peshawar in May 2000, the government had erected a mock-up of the Shaheen-2 missile inside a major traffic circle, with the slogan underneath, “I’d love to enter India.”

Traditionally, both India and the United States also worry about the Pakistani “loose nukes” problem, given the frequency of coups in Islamabad and how Pakistan’s terror sponsorship often ends in backlash within its own borders. The Pentagon reportedly has plans to send U.S. Special Forces into Pakistan to secure and extract its nuclear arsenal should the government ever collapse, lest the nuclear weaponry fall into the hands of Al Qaeda or Jamaat-e-Islami-affiliated terror groups.

While a belligerent terror sponsor on India’s border is a strategic liability, it is one India can handle decisively as Operation Sindoor showed.

Turkey, however, will pose a greater challenge: A belligerent terror sponsor 4,500 kilometres away. While that might seem a better prospect, the danger is that Ankara may believe it has the distance and strategic depth to immunize itself from the consequences of its use in a way Islamabad never could. The United States might be asleep or naïve about Turkey, but Israel has woken up to the threat a Turkish nuclear weapons program would pose; India should do so as well.

With U.S. aircraft carriers converging on the Indian Ocean with speculation that they will soon target Iran’s nuclear and missile programs, how could Turkey pose a greater threat than Iran or Pakistan?

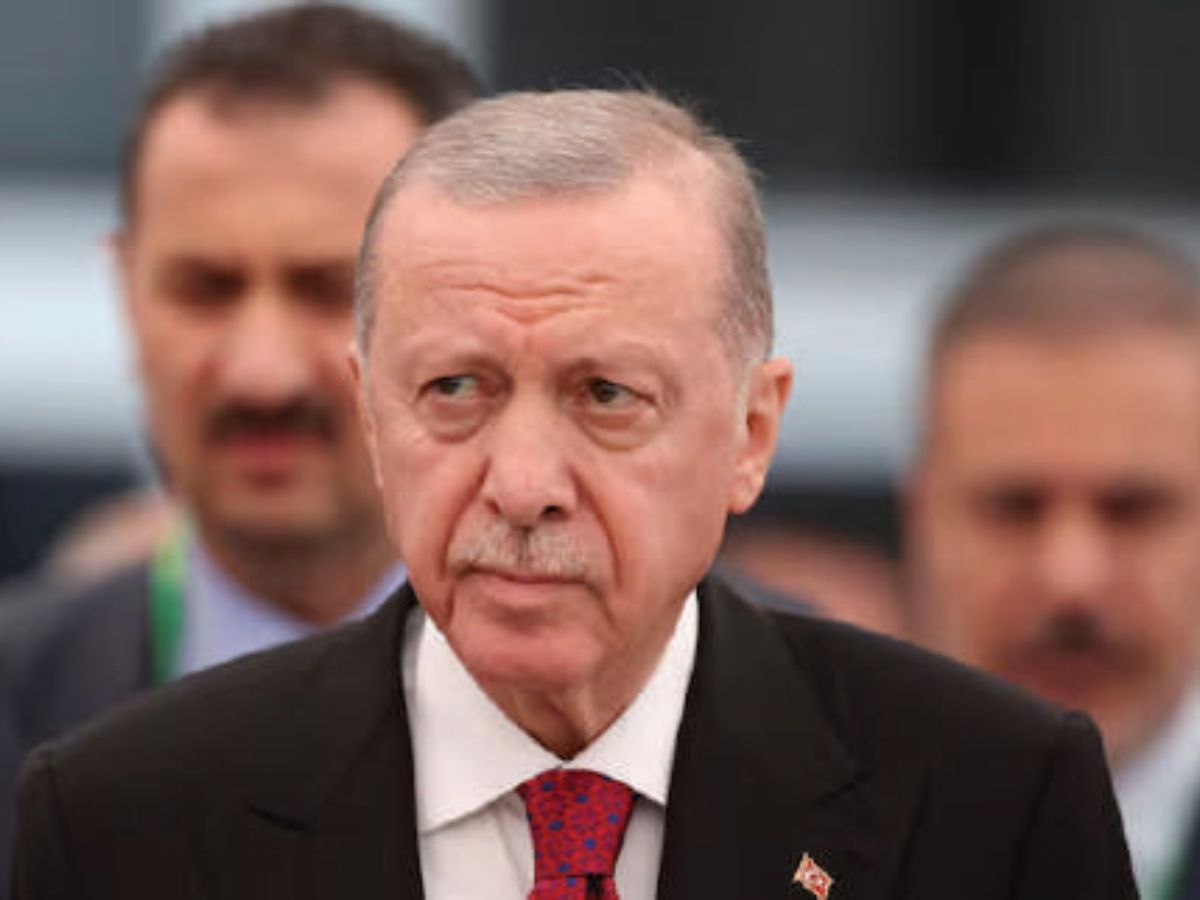

The answer is the combination of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s Islamist ideology and Turkey’s nearly 75-year-old NATO membership. Unlike Pakistan and Iran, Turkey can develop its nuclear capabilities behind NATO’s Article V protections that define an attack on one as an attack on all. Erdoğan may be as committed to terror as much as Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, rogue nuclear scientist A.Q. Khan, Pakistan Army Chief Asim Munir and Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, but unlike Pakistan or Iran, he need not fear unilateral strikes taking out his capabilities. India hobbled Pakistan airfields during Operation Sindoor, and Israel and the United States took out Iranian nuclear and anti-aircraft facilities, but Turkey’s NATO membership renders such unilateral action more difficult.

Because NATO has no mechanism to oust a wayward member, Turkey can use NATO as a shield as it grows a program every bit as lethal as Pakistan and Iran’s. U.S. naivete and European greed and susceptibility to blackmail heighten the Turkish threat. The European Union resists meaningful action against Turkey in fear that Erdoğan will unleash waves of migrants or activate Turkish sleeper cells, while Turkey bribes President Donald Trump’s family and friends with promises of investment or business deals.

That, and Turkey’s advanced industrial and engineering capabilities mean a Turkish rush for a bomb would be quicker than the quarter century it took Pakistan or the four decades Iran invested in its program. If Turkey wants a bomb, especially with this year’s opening of its Akkuyu nuclear reactor, it likely can achieve it within five years.

While Erdoğan’s chief animus is toward the Jewish state, he holds all non-Muslims in near equal disdain and dismisses the legitimacy of any government like India’s where non-Muslims can rule over Muslims. Whether India’s Ministry of External Affairs recognizes it or not, Turkey already engages in a multifront war with India, using charities and media to undermine its legitimacy and sponsoring terrorist groups to target it through Pakistan.

At a minimum, with nuclear weapons, it will feel itself emboldened to increase its activities absent the constraints of falling within India’s range of conventional pre-emption. Just as Khamenei grows more radical with age, so too does Erdoğan, who has delusions of becoming a new Ottoman sultan if not Islamic caliph.

-

Michael Rubin is director of policy analysis at the Middle East Forum and a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, DC.