Keeladi’s discoveries reshape Indian history, placing the Sangam Age as a key pillar of India’s ancient urban and cultural legacy.

History is not a frozen portrait of the past, instead it presents itself as a living dialogue, constantly reshaped by new discoveries and fresh interpretations. As the distinguished historian James M. McPherson aptly said, “…revision is the lifeblood of historical scholarship. History is a continuing dialogue between the present and the past. Interpretations of the past are subject to change in response to new evidence, new questions asked of the evidence, and new perspectives gained over time.

There is no single, eternal, and immutable “truth about past events and their meaning.” Nowhere is this evolving nature of history more evident than in the rediscovery and recognition of the importance of the Sangam Age, which has moved from the margins of India’s historical imagination to a central place in its civilizational journey.

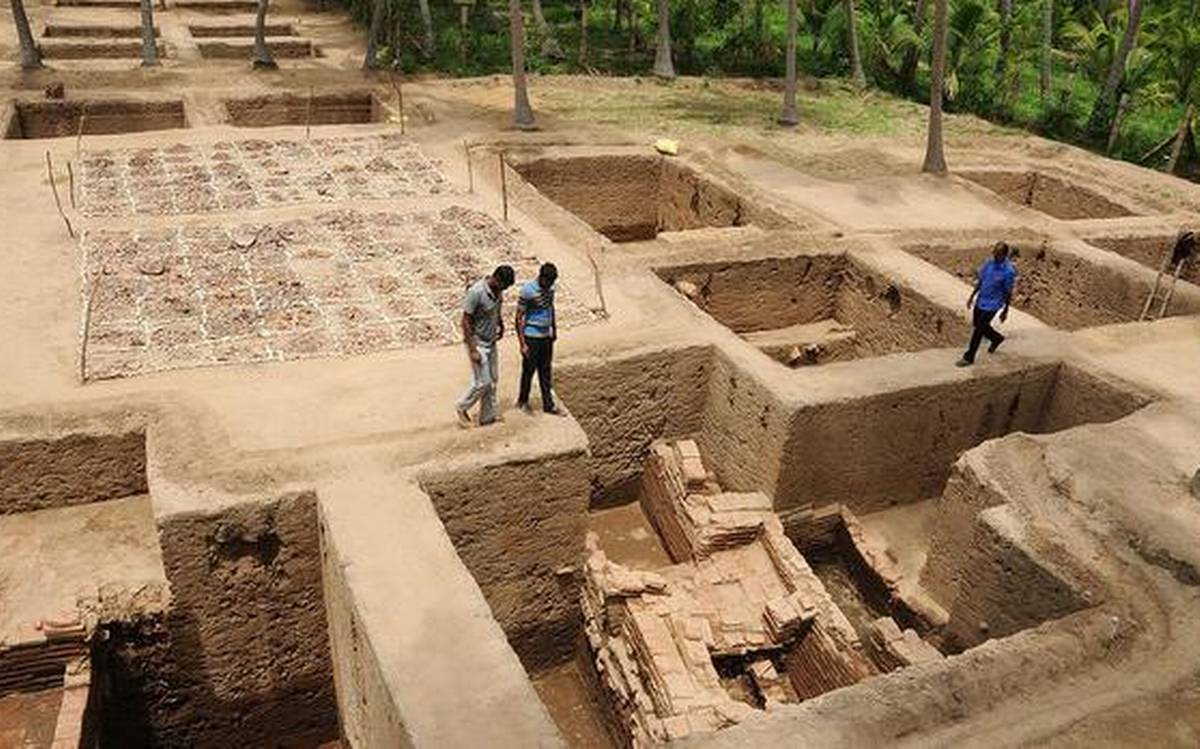

The Sangam Age is known primarily through its unparalleled literary legacy for generations. Tamil Sangam poetry, often dated between the 3rd century BCE and 3rd century CE, dazzled scholars with its emotional depth and cultural richness. A.K. Ramanujan, a master translator of Tamil classics, once praised these poems for their striking balance of “passion and courtesy, impersonality with vivid detail, austerity with richness.” He posed a timeless question: What kind of material culture could give rise to such exquisite literary expression? Until recently, the historical backdrop of this literary world remained elusive. But the dramatic findings at Keeladi, a settlement along the Vaigai River, have answered Ramanujan’s question in the most spectacular fashion. Far from the image of a simple, rural society, Keeladi reveals an ancient urban centre with evidence of advanced civic planning, composed of straight streets aligned in cardinal directions, wellstructured brick houses, drainage systems, and a flourishing artisan economy.

Keeladi’s artefacts speak volumes, be it pottery inscribed with Tamil Brahmi script, ivory dice indicating leisure and social stratification, or graffiti reflecting astronomical awareness. These crucial finds present a tangible, archaeological counterpart to the Sangam poets’ vivid imagination. The world of high literary sophistication described in Purananuru, Kuruntokai, and other texts has been mirrored by an equally advanced material culture on the ground. Even more striking remains the philosophical depth of the Sangam literature. Take, for instance, Purananuru Poem 192, which proclaims: “Every city is your city. Everyone is your kin.” This inclusive, almost cosmopolitan worldview challenges the notion that ancient societies were tribal or insular. Such a combination of high literary artistry and urban material culture suggests that the Sangam society possessed a civic and ethical maturity well ahead of its time.

Perhaps the most revolutionary development in recent years has been the radical redating of the Sangam Age. Traditional scholarship situated the Sangam period between 300 BCE and 300 CE. However, recent carbon-dating evidence from Keeladi has decisively shifted this timeline. In 2019, the Tamil Nadu State Department of Archaeology dated artefacts from Keeladi to between the 6th century BCE and 1st century BCE, with some samples even dating back to around 580 BCE. Even more ground breaking, the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), under archaeologist K. Amarnath Ramakrishna, further pushed these dates back to around 800 BCE. These discoveries have staggering implications. They place the emergence of Tamil urbanism as roughly contemporary with early urban developments along the Gangetic plains and not centuries later, as previously assumed. Such evidence challenges long-standing historical narratives that centre India’s ancient civilizational identity exclusively around the GangeticVedic axis.

Tamilakam’s early urbanism should encourage historians to rethink simplistic binaries of “north versus south” or “Sanskritic versus Dravidian.” Instead, it affirms a plural and interconnected Bharatiya civilizational landscape where diverse cultural streams evolved in parallel. Language and scripts further buttress such arguments as they enrich our understanding of this vital period of history. Tamil Brahmi inscriptions at Keeladi predate Ashokan Brahmi, indicating veritably that Tamil literacy developed independently and early. Moreover, epigraphists like K.V. Subrahmanya Aiyar and Iravatham Mahadevan have long argued for the indigenous evolution of Tamil Brahmi, a position now corroborated by archaeological data. More importantly, graffiti on ordinary artefacts indicates that literacy was not restricted to elites but percolated through broader society.

The Sangam Age’s significance transcends Tamilakam. It opens up larger civilizational debates about the deep antiquity of Indian society and the interlinkages between ancient cultures. Iravatham Mahadevan’s meticulous research on the Indus script led him to argue that the language of the Indus Valley civilization was Dravidian. His magisterial work, “The Indus Script: Texts, Concordance and Tables”, remains a cornerstone for understanding the possible cultural and linguistic continuities between ancient northwestern and southern India. American archaeologist Gregory Possehl famously acknowledged Mahadevan’s methodological rigour, praising his clarity and caution in drawing conclusions. Adding further depth, R. Balakrishnan’s monumental book “Journey of a Civilization: Indus to Vaigai” argues that there was not a rupture but a gradual southward diffusion of civilizational elements after the decline of the Indus Valley Civilization.

Balakrishnan uses human geography tools, such as mapping trade routes, river valleys, and settlements, to demonstrate cultural and technological continuities from Harappa to Tamilakam. Shared cultural symbols, common motifs, similar burial practices, and parallels in script and iconography suggest a wider interconnected civilizational matrix within the Indian subcontinent. Looking at this way, Keeladi’s discovery is not just about Tamil pride, but it offers us a window into a more holistic and integrated understanding of Bharatiya antiquity where multiple civilizational centres flourished across time and geography. Such discoveries are relevant today as they compel us to transcend regional chauvinism and recognize that Indian history is not a single-threaded narrative dominated by one cultural stream. Such a vibrant tapestry woven from many threads, Vedic, Dravidian, tribal, Buddhist, and beyond, forms the idea of Bharat itself.

The rediscovery of the Sangam Age has transformed our understanding of ancient Indian history. From the poetic brilliance of the Sangam corpus to the material sophistication unearthed at Keeladi, from the redefined timelines of urbanism in Tamilakam to the enduring civilizational linkages with the Indus Valley, we see the evidence of a profound reimagining of India’s civilizational journey. As we peel back the layers of time, we find that the Sangam Age was never a marginal footnote or sporadic episode, but it must be viewed and treated as it was: a thriving epicentre of cultural, intellectual, and urban life. This chapter of history demands acknowledgment not as a regional peculiarity, but acceptance as the foundational pillar of India’s civilizational edifice.

By embracing this plural history, we must enrich our collective understanding, recover our civilizational memory, which was inclusive, sophisticated, and enduring. Recognizing and respecting the past is the only way that cultural and civilizational renaissance that we seek in Amrit Kaal, is possible. The past, it turns out, with the Sangam Age, is one more proof that we were an outward civilization that influenced other cultures, which falsifies the Aryan Invasion Theory, a colonial construct.

Prof. Santishree Dhulipudi Pandit is the Vice-Chancellor of JNU.