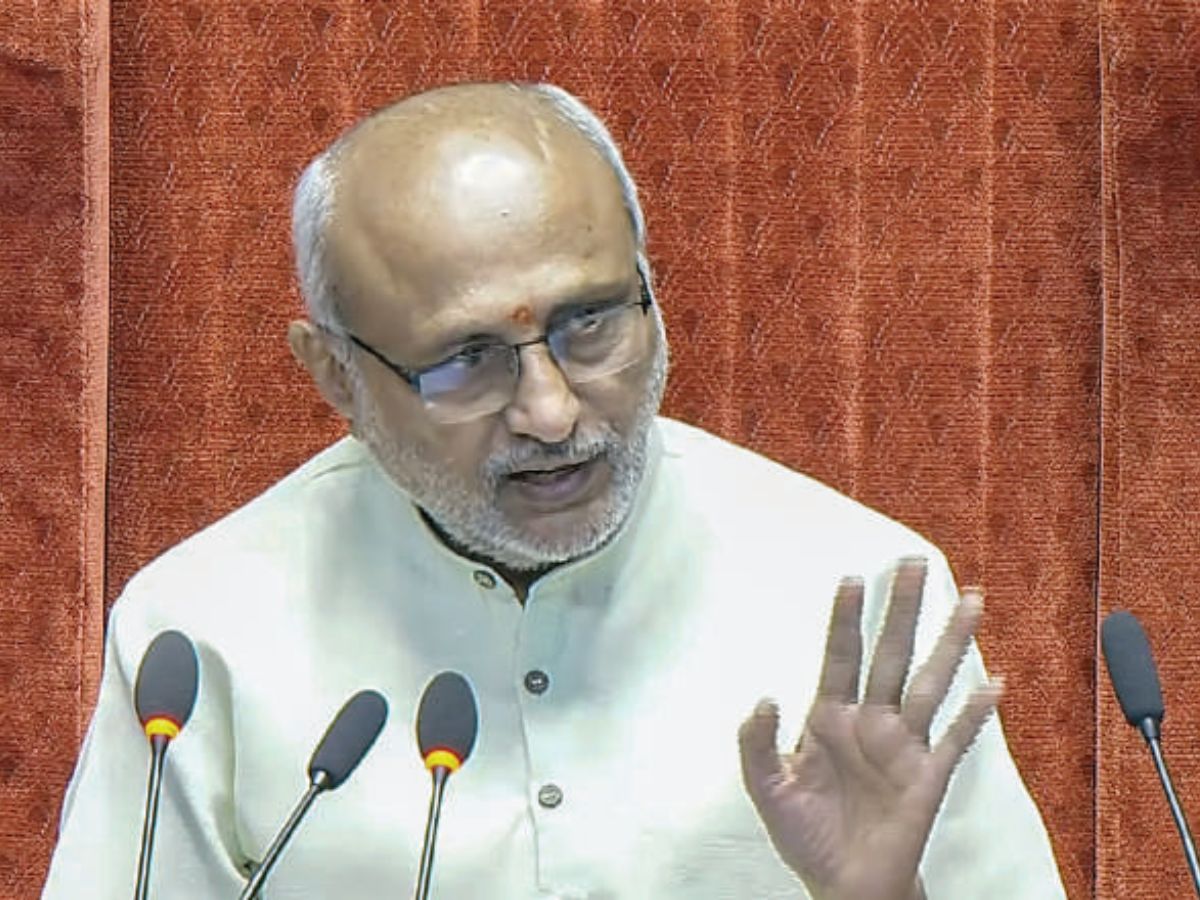

On the opening day of the current Winter Session, India’s newly elected Vice-President and Rajya Sabha Chairman, Shri C.P. Radhakrishnan, walked into the chambers to take the chair. The air was thick with ceremony—and, quietly, with suspicion. Opposition leaders used the occasion not simply to extend courtesy, but to issue premature warnings about “impartiality,” signalling in effect that the moment the Chair begins its duty, its every action will be viewed through a lens of partisan mistrust. Media headlines echoed the sentiment: the Opposition insisted that Shri Radhakrishnan needed to “maintain neutrality,” implicitly suggesting they would treat any enforcement of procedure with scepticism.

This is the context for the argument that follows: that today in India, the invocation of “bias” against Speakers and Chairs has increasingly become a pre-emptive, strategic assault on constitutional authority. This is not vigilance; it is delegitimisation. I say this also from institutional experience. Having served as a member of the Panel of Vice-Chairpersons of the Rajya Sabha, and having been entrusted with that responsibility at a relatively young age, I have seen at close quarters what impartiality demands in practice—the discipline of foregoing personal or political preference in order to uphold procedure. It is this firsthand understanding of the responsibility and restraint neutrality requires that underpins the concern expressed here.

From the very inception of India’s constitutional framework, neutrality of the Chair was not treated as an optional virtue but as an indispensable condition of parliamentary democracy. Dr B.R. Ambedkar was categorical on this point. In the Constituent Assembly, he repeatedly emphasised that the Speaker or presiding authority must command confidence across the House, and that such confidence rested entirely on the perception and practice of impartiality. The Chair, in Ambedkar’s conception, was not another player in the political arena, but the institutional anchor that allowed contestation to occur within rules rather than collapse into disorder. Once elected, the occupant of the Chair was expected to rise above party affiliation and act as a constitutional trustee of procedure.

This expectation was not left to goodwill. It was secured through deliberate design. Ambedkar supported safeguards that insulated the office from casual attack: special procedures for removal, strict limitations on discussing the conduct of the Chair except by substantive motion, and financial security independent of executive discretion. The Speaker or Chair was thus conceived as a constitutional safeguard, not a partisan instrument—an office defined as much by restraint as by authority.

In today’s parliamentary practice, allegations of bias seldom arise when the Speaker or Chair presides over a vote and one side clearly loses by numbers. They arise instead when the Chair enforces the rules of the House—by disallowing notices that do not meet procedural requirements, insisting on order during proceedings, curbing repeated disruptions, or applying standing rules uniformly to all members. These decisions are procedural, not political. They do not decide legislative outcomes; they decide whether Parliament can function with discipline and dignity.

Because procedural rulings do not involve visible vote counts or clear winners and losers, they are easier to misrepresent. When rules are applied evenly but one side finds itself restricted more often due to its own misconduct, charges of bias quickly follow. Enforcement of procedure is portrayed as “discrimination”, and insistence on maintaining order is recast as “political hostility”. Over time, this creates a troubling reversal: the more firmly and consistently the Chair upholds parliamentary rules, the more “biased” the Chair is alleged to be—not because neutrality has been abandoned, but because parliamentary discipline limits unsolicited disruption. In effect, neutrality is punished precisely when it is exercised.

This dynamic was acutely understood by Shri Somnath Chatterjee, one of the most widely respected Speakers in India’s parliamentary history. Responding to accusations against him, Chatterjee warned that indiscriminate allegations of bias do not merely criticise the individual occupying the Chair; they damage the credibility of Parliament itself. He drew a clear distinction between legitimate disagreement with rulings—which he described as inherent to democracy—and unfounded attacks on the neutrality of the office. To cast aspersions on the impartiality of the Speaker, he argued, was to erode the institution that protects the rights of all members, including the opposition.

The contemporary political incentive structure, however, rewards precisely this erosion. Alleging bias is easy. It requires no evidence, no constitutional motion, and no willingness to submit to institutional scrutiny. It attracts immediate attention and media amplification. Challenging the Chair through constitutionally prescribed means—by placing facts on record and invoking formal procedure—is difficult and politically risky. Unsurprisingly, slogan replaces substance, and accusation replaces argument.

The consequences are not abstract. They are visible inside the House every day. Time that should be devoted to matters of national importance—national security, economic growth, health, education, social justice—is consumed by sloganeering and repeated adjournments. Members who rise to raise genuine issues on behalf of their constituents are obstructed not by counterargument, but by noise. Parliamentary duty is displaced by “performative protest” aimed at political limelight.

This is not merely a breakdown of decorum; it is a democratic loss. Parliament exists to deliberate, legislate, and hold the executive accountable. When sittings are paralysed by manufactured controversy around the neutrality of the Chair, citizens are denied representation in practice even if it exists on paper. The obstruction of the House directly obstructs governance.

The ripple effects extend well beyond the walls of Parliament. Legislative delays slow policy reform, oversight weakens, and economic decision-making is burdened with uncertainty. In this sense, the deliberate obstruction of parliamentary functioning is not merely opposition to the government of the day; it amounts to opposition to national progress itself. Growth, reform, and effective governance depend on a legislature that can transact its business with seriousness and continuity.

Equally important is the example Parliament sets. The conduct of Members within the House is closely watched, particularly by young Indians for whom democratic institutions are being shaped in real time. When disruption and accusation replace debate and responsibility, it is not only governance that suffers, but the democratic ethic we pass on to the next generation.

None of this denies the legitimacy of criticism. Dr Ambedkar himself recognised that constitutional offices must be accountable. But accountability was to be exercised through procedure, not spectacle. There is a crucial difference between good-faith, reasoned critique of specific rulings; structural critique of constitutional arrangements; and the weaponisation of “bias” as a slogan to paralyse parliamentary proceedings. Collapsing these distinctions impoverishes democratic discourse.

It is in this context that public insinuations against Vice-President and Rajya Sabha Chairman Shri C.P. Radhakrishnan, voiced at the very moment he assumed office, must be viewed. These were not responses to any ruling or action, but pre-emptive declarations of mistrust. Such gestures do not strengthen democracy. They weaken the institutional trust without which no presiding authority can function effectively.

This is a choice before us. We may choose a Parliament governed by rules, restraint, and reasoned disagreement. Or we may choose a Parliament paralysed by suspicion, where disruption substitutes debate and allegation substitutes accountability. Neutrality of the Chair is not a favour to an individual; it is a protection for the institution and, ultimately, for the citizen.

As Dr Ambedkar envisioned and as Somnath Chatterjee reminded us through practice, the Chair must remain above “partisan combat” if Parliament is to serve the nation. Undermining that principle for political gain may yield momentary attention, but it carries a permanent cost—to parliamentary functioning, to democratic credibility, and to the country’s capacity to move forward.

-

Kartikeya Sharma is an Independent Member of Parliament (Rajya Sabha).