India has used its minimum deterrence and no first use nuclear postures to drive international confidence. But both increasingly seem inadequate for its dire security needs.

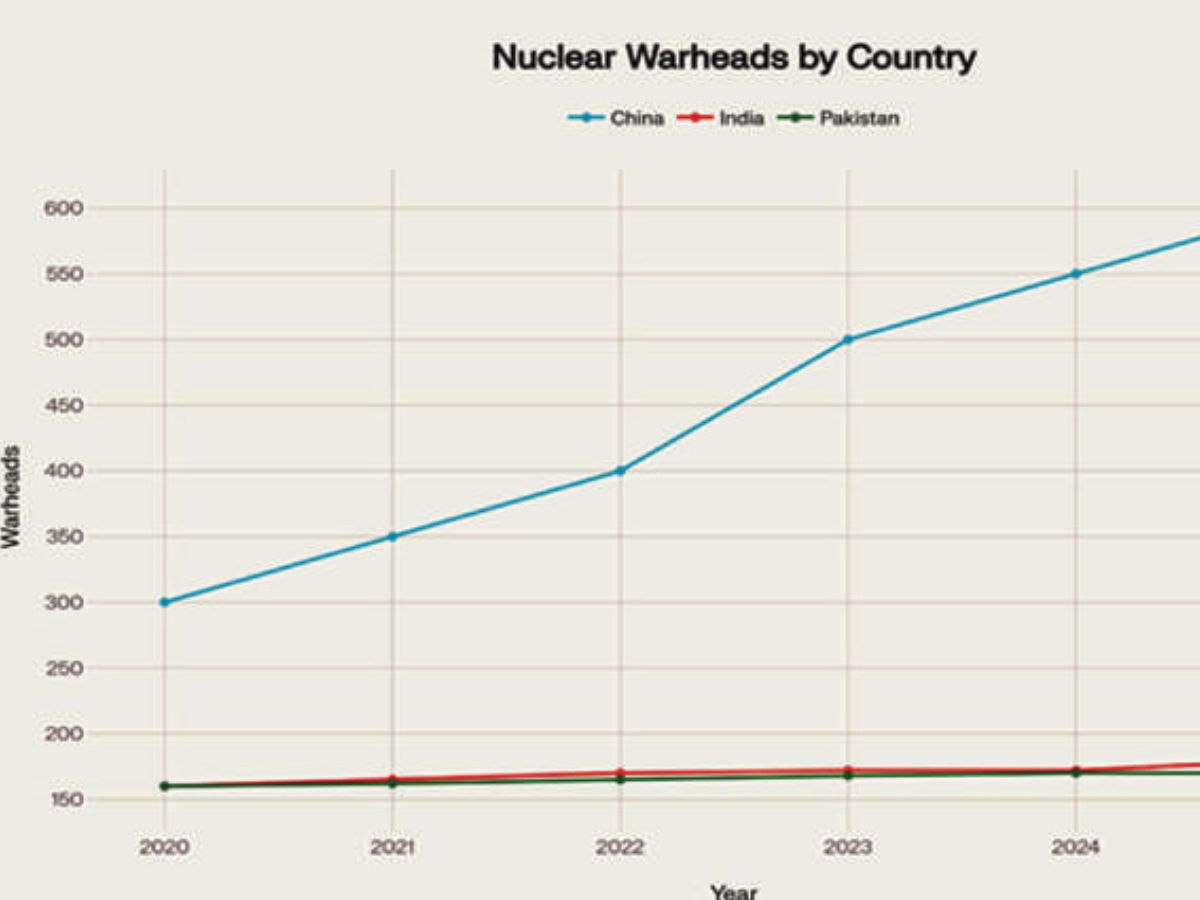

Collated from public sources.

New Delhi: In May 1998, India’s Pokhran-II tests redrew the global strategic map, announcing its arrival as a declared nuclear-weapon state. The doctrine that followed was one of prudence and responsibility: “Credible Minimum Deterrence” built on a “No First Use” (NFU) pledge. For over two decades, this posture has been the bedrock of India’s strategic stability, a guarantee of its sovereignty. But today, that hard-won deterrence is facing an unprecedented, pincer-like squeeze, and its credibility is eroding. Caught between a rapidly expanding, high-tech Chinese arsenal and a doctrinally aggressive, tactical-minded Pakistan, India’s “minimum” posture is being dangerously outmatched. The strategic realities of 2025 are not those of 1998. The “minimum” is no longer “credible” when faced with China’s “massive” and Pakistan’s “full spectrum.” This new, harsh reality demands a sober and urgent re-examination of India’s entire nuclear doctrine and force structure, before its strategic deterrent is weakened beyond repair.

The most significant challenge to India’s deterrence is the sheer, unadulterated math of China’s nuclear expansion. India’s “minimum deterrence” was always predicated on an adversary that, while larger, was also believed to maintain a “minimum” arsenal. That assumption is now dangerously obsolete. According to the latest January 2025 estimates from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), China’s nuclear arsenal has swelled to an estimated 600 warheads. In the same period, India’s stockpile is estimated at 180. This gap of 420 warheads is stark, but the most alarming statistic is the rate of change. In just one year, from 2024 to 2025, China is estimated to have added 100 warheads to its arsenal. India added eight. Forecasts suggest China’s warhead count might exceed 1,000 by 2030.

This is not a gradual modernization; it is a nuclear breakout. China is on a trajectory to possess at least 1,000 warheads by 2030, a number that would put it on par with the Cold War-era “superpower” levels of Russia and the United States. This quantitative leap is backed by a terrifying qualitative transformation. China is finalizing a mature nuclear triad that dwarfs India’s:

On Land: Beijing is constructing over 350 new missile silos for its advanced solid-fuelled intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) like the DF-41, which can carry multiple warheads (MIRVs) and strike any target in India.

At Sea: Its fleet of at least six Type 094 (Jin-class) nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) patrols with long-range JL-3 submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), giving it a survivable “second-strike” capability from the deep ocean.

In the Air: Long-range H-6N bombers, capable of carrying air-launched ballistic missiles, complete the triad.

This physical expansion is accompanied by a frightening, albeit unconfirmed, doctrinal shift. While China officially maintains a “No First Use” policy, its construction of a massive, silo-based ICBM force and advanced early-warning systems strongly suggests a move toward a “Launch on Warning” (LOW) posture. This means China would not wait for an enemy’s missile to land before launching its own; it would launch upon detecting an inbound attack.

For India, this changes everything. The fundamental question for Indian strategists is now this: How can a “minimum” deterrent of 180 warheads, maintained at a lower state of readiness, “credibly” threaten a nation with 600 (and soon 1,000) warheads, advanced missile defences, and a LOW posture? The logic of “assured retaliation,” which underpins India’s NFU, begins to crumble. China’s growing arsenal threatens to overwhelm India’s deterrent, creating a scenario where Beijing might believe it could launch a first strike and intercept or absorb India’s “minimum” response.

If China’s challenge is one of strategic, high-end “overmatch,” Pakistan’s is one of tactical, low-threshold “outflanking.” While public discourse often focuses on the India-Pakistan nuclear “race,” the latest data shows a different story. India (180 warheads) has a marginal numerical lead over Pakistan (170 warheads). The challenge from Islamabad is not quantitative, but qualitative and doctrinal.

Pakistan has adopted a policy of “Full Spectrum Deterrence.” This doctrine is an explicit response to India’s conventional military superiority. Fearing a conventional blitzkrieg from India, Pakistan has developed and advertised its arsenal of Tactical Nuclear Weapons (TNWs), specifically the short-range (60-70 km) Nasr missile. These are not strategic weapons designed to destroy cities; they are low-yield battlefield weapons designed to be used against large Indian troop formations on the battlefield to stop a conventional advance.

This development checkmates India’s conventional forces and poses an existential dilemma to its nuclear doctrine. The problem is a “crisis of credibility” for India’s “massive retaliation” plank. Consider the scenario Pakistan has designed its doctrine for:

Indian forces launch a conventional offensive into Pakistani territory.

To halt this advance, a Pakistani field commander uses a single, low-yield Nasr TNW against the Indian troop column.

According to India’s stated doctrine, a nuclear attack would be met with “massive retaliation... designed to inflict unacceptable damage.” Does this mean India would launch a strategic strike against a Pakistani city like Lahore or Karachi in response to a tactical strike on its troops? This response is widely seen as non-credible. The international condemnation, the risk of all-out strategic nuclear war, and the sheer disproportionality of the act make it an almost unusable option. But if India doesn’t retaliate massively, or has no credible response at all, its nuclear deterrence has failed. Pakistan will have successfully used a nuclear weapon to win a conventional conflict.

This is the “doctrinal squeeze.” Pakistan’s “first-use,” tactical-weapon policy is designed to neutralize India’s $200B+ conventional military. It lowers the nuclear threshold from a deterrent of last resort to a tool of battlefield management, and it corners India into an impossible “suicide-or-surrender” choice.

THE TWO-FRONT SQUEEZE

India’s strategic planners are therefore in the unenviable position of being squeezed from two opposite directions simultaneously. They must build and maintain a nuclear force that can:

Deter China: A high-end, strategic peer with a massive, growing, and highly survivable arsenal. This requires a large, sophisticated, and survivable force capable of inflicting “assured” damage even after a potential Chinese first strike.

Deter Pakistan: A low-end, tactical adversary that has declared its willingness to use nuclear weapons first on the battlefield. This requires a flexible, scalable, and credible response that is less than “massive” but still “punitive,” to avoid the trap of inaction.

India’s current “one-size-fits-all” doctrine of “Credible Minimum Deterrence” and “Massive Retaliation” is woefully insufficient for this complex, two-front reality.

This is not to say India has been idle. Its scientific establishment has delivered remarkable successes. The recent “Mission Divyastra” test, which proved India’s MIRV (Multiple Independently-targetable Re-entry Vehicle) capability on the Agni-V missile, is a monumental achievement. A MIRV-capable missile can carry multiple warheads to strike different targets, acting as a force multiplier and a potent tool for overwhelming missile defences.

Furthermore, India’s nuclear triad is now functional. The INS Arihant and INS Arighaat, India’s indigenous SSBNs, provide the “assured” second-strike capability that is the absolute bedrock of a No First Use policy.

But these achievements, while necessary, are no longer sufficient. The Arihant-class submarines are currently armed with the shorter-range K-15 missile, limiting their patrol “bastions” to areas close to India’s shores, where they are more vulnerable. More longer-range K-4 missiles, whose testing has been promising, are needed urgently to allow these submarines to disappear into the vastness of the Indian Ocean. And while India’s MIRV is a breakthrough, it cannot single-handedly offset the sheer pace of China’s production, which is adding 100 warheads per year.

India’s nuclear doctrine was a product of its time—an era of strategic optimism and a belief in “minimum” deterrence. That era is over. The new reality is a two-front nuclear threat that is not just theoretical but physically visible in the satellite images of new Chinese silos and the doctrinal declarations from Rawalpindi. The “minimum” deterrent is no longer “credible” when an adversary’s arsenal is this massive and its doctrine is this aggressive.

This is not a call for a reckless, open-ended arms race. It is a call for a sober, realistic, and urgent national re-evaluation. The questions India’s strategic community must now debate, behind closed doors and in the public sphere, are profound and urgent:

What does “minimum” mean in the 2030s? Can a force of 180-200 warheads truly deter a 1,000-warhead China? A reassessment of the “minimum” number required for “assured” retaliation is imperative.

How does “No First Use” remain credible? How does India respond to a Pakistani TNW strike without either backing down or triggering Armageddon? This may require a review of the “massive retaliation” clause to include options for a “flexible” or “proportionate” response.

Is the pace of modernization sufficient? The K-4 missile, the S-5 submarine, and the wider deployment of MIRV-capable missiles are no longer just “future” projects; they are immediate strategic necessities, and these programmes must be further expanded.

The 1998 tests bought India strategic autonomy. The decisions made in the next few years will determine if it can preserve it. India must urgently recalibrate arsenal size and structure; move beyond mere “minimum” numbers, and assess what genuinely assures retaliation against the evolving China-Pakistan threat.

This may require raising the arsenal to a larger number (200-250 warheads by 2030), with more ready-to-use (mated) warheads and restructuring deployment to ensure survivability, especially given China’s counter-force buildup. India must prioritize rapid MIRV deployment and related penetration aids to maintain the ability to threaten multiple dispersed targets and defeat missile defences. Without this, India risks losing even minimum strike credibility. It must harden and diversify command and delivery systems. Invest in more robust and survivable command and control, including mobile and hidden launchers. Expand and operationalize the SSBN fleet and sea-based capabilities to ensure true second-strike potential. Harden infrastructure and introduce redundancy to frustrate adversary “decapitation” or counter-force attempts.

India may need to make elements of its doctrine less predictable to adversaries. Options include: ambiguity in warhead deployment and retaliatory thresholds, reviewing the NFU pledge in light of China’s and Pakistan’s more aggressive stances, and ensuring speed and certainty in escalation, while maximizing survivable retaliatory options—what some analysts term “minimum credible flexibility.” While ramping up capabilities, India should also engage proactively in regional and global arms control forums, highlighting transparency, advocating for no first use as a multilateral norm, and discouraging new entrants and accidental escalation regionally. However, self-imposed restraint must not become a substitute for credible capability.

Hindol Sengupta is professor of international relations at the O. P. Jindal Global University, and director of the Jindal India Institute.