Most assessments of Modi’s electoral success are wrong. What keeps him in power is crafting of a new welfare state model.

New Delhi: To understand why Narendra Modi will win again, if he chooses to contest, in 2029, you have to look at what is failing across Europe, the US, and especially the UK. Reams have been written about the unbeaten track record of India’s now three-term Prime Minister but the analysis has mostly focused either on social and ideological campaigns or astute construction of an electoral machinery that is agile and responsive. But this is only one part of the story.

The part that remains under-studied is the construction of a new welfare state by Modi which has emerged as an alternative to the Western welfare state model. In 2019, I wrote the first paper on this for the Observer Research Foundation (“The economic mind of Narendra Modi”), and since then the argument has become exponentially stronger. As the Western welfare model that sustained Western democracies since the end of the Second World War when the term “welfare state” spearheaded by the Labour Party post-war government and the Beveridge Report (which created the National Health Service) crumbles, India is showing the future of what a new welfare model could look like.

FROM A PATRONAGE SYSTEM TO A LEAK-PLUGGING MODEL

The Modi era has been defined by a paradigm shift from a patronage-based, leaky welfare system to one that is targeted, transparent, and technology-driven. Enough has been said about the benefits of digitisation in this process. But its core elements are worth noting: streamlining and digitizing delivery (Direct Benefit Transfer, Aadhaar, JAM Trinity), centring the Prime Minister’s Office in welfare attribution, and scaling eligibility outreach and central budgeting for flagship schemes, widening both urban and rural nets.

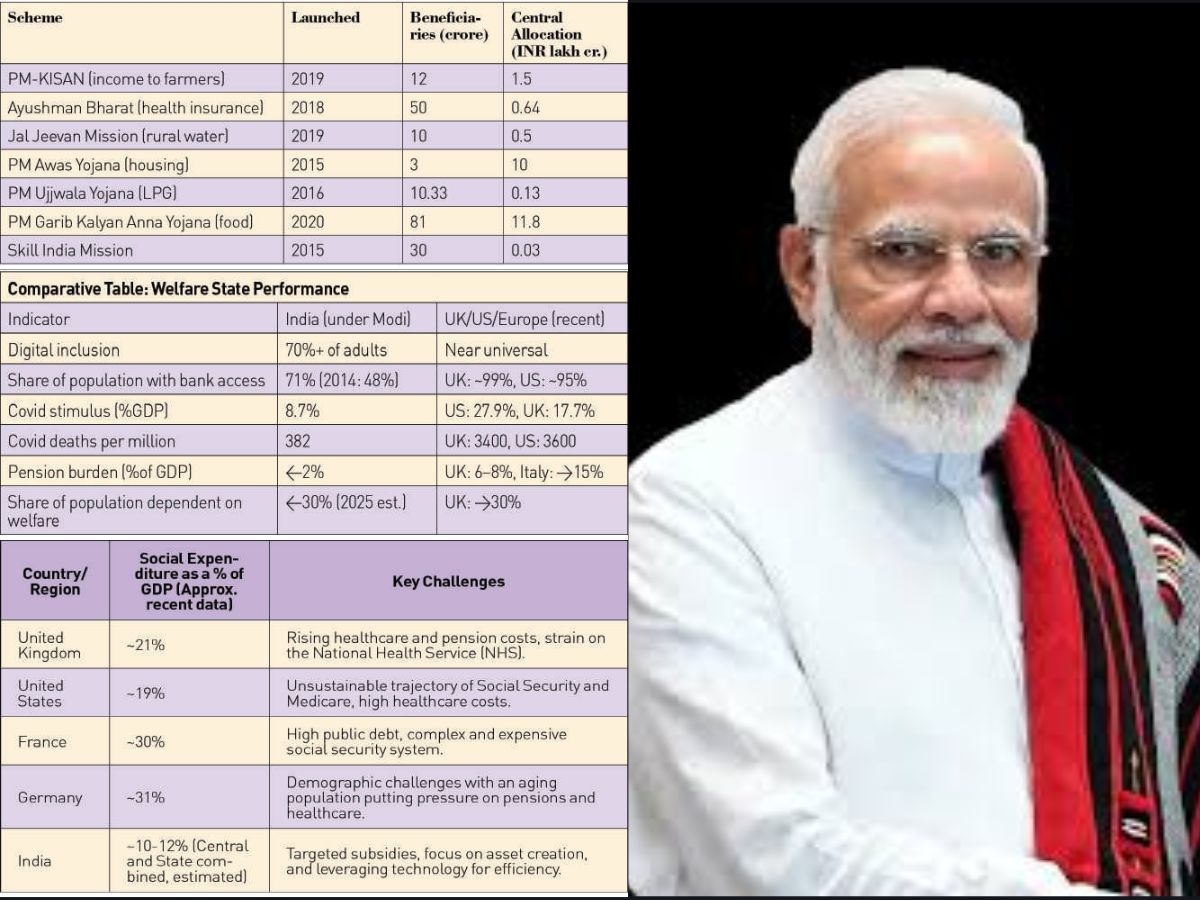

Modi’s government has launched or hugely expanded numerous welfare programs as seen in Table 1. Source: Collated from government websites. Other impactful schemes include the Jan Dhan Yojana: 50+ crore bank accounts opened, deepening financial inclusion, the Pradhan Mantri Suraksha Bima Yojana and the Pradhan Mantri Jeevan Jyoti Bima Yojana which is likely to cross 75 crore insurance enrolments by 2025, the Atal Pension Yojana, Beti Bachao Beti Padhao, Swachh Bharat mission for sanitation, and Eklavya schools for tribal children.

In a definitive move, and unlike many advanced economies that risked massive fiscal overruns during the Covid-19 pandemic, India under Modi combined targeted relief with relatively restrained stimulus. India’s total fiscal stimulus during the pandemic amounted to 8.7% of GDP, sharply below the US (27.9%), UK (~17%), and Japan (~50%). Despite this, India sustained and even expanded the free food distribution scheme (PM Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana), covering 81 crore beneficiaries as the world’s largest such program. Direct income and in-kind transfers helped avoid mass destitution even during lockdowns.

India managed to keep economic growth relatively intact despite global shocks. GDP contraction in 2020-21 was acute (-7.3%), but rebound began soon with consumption and welfare nets cushioning the shock. The structure of spending focused not only on immediate relief but durable expansion of basic services (housing, water, health, insurance, food security). Most dramatically, India has among the world’s lowest per capita Covid-19 death rates. Even broad measures show the difference. Covid deaths per million: ~382 for India, compared to 3,500 for the US, 3,300 for UK, and 2,000 for Germany as of 2025. The gap is vast even taking into account that data reporting standards may vary.

CRISIS OF THE WESTERN WELFARE STATE

The West now faces a very different trajectory. Once the gold standard for welfare, the UK, US, and most of Europe now encounter mounting crises. Britain’s long-term sick and disability claimants are at record highs (2.8 million jobless, 1 in 10 of working age on sickness benefits), with annual spending on health-related benefits up by 44% since 2020; political resistance to reform is acute. The UK’s welfare state has been repeatedly retrenched and “austeritised” since 2010, then saw massive pandemic-era outlays (£30 billion of emergency increases in 2024 alone), but failed to curb rising inequality and dependency. The US struggled with fragmented social safety nets, spiralling pandemic costs, and major gaps in coverage for health and unemployment, which led to social unrest and persistent inequalities.

In many European countries, the combination of aging populations, pension commitments, high structural unemployment and permanent “emergency” outlays post-Covid have rendered welfare spending fiscally unsustainable to a degree not seen in India. Economic recovery in the UK, parts of Europe, and the US post-Covid was dampened by debt burdens and inability to contain welfare outgo beyond public means.

A comparison between the public debt of these countries would show how this situation is set to aggravate. The UK and France show exceptionally high public debt levels relative to GDP, both around 100% debt-to-GDP ratio. The US clocks in at 124%. In comparison, India has a more modest debt-to-GDP ratio at about 80%. India has been meticulously crafting a sustainable and targeted welfare state, whereas many Western economies are grappling with the imminent collapse of their own welfare models.

Decades of universal entitlements, untargeted subsidies, and ever-expanding social security nets have created a fiscal quagmire that is becoming increasingly untenable. The welfare states in the West are characterized by deep financial unsustainability, with decades of promising ever-increasing benefits without commensurate economic growth have led to staggering levels of public debt. The demographic shift towards an aging population further exacerbates this problem, with a shrinking workforce supporting a growing number of retirees.

Large, unwieldy bureaucracies often consume a significant portion of the welfare budget in administrative costs, reducing the amount that reaches the intended beneficiaries. In some cases, generous unemployment and other benefits have been criticized for creating a “welfare trap”, where individuals are better off financially on welfare than in low-paying jobs, leading to a decline in labour force participation.

India, in contrast, has adopted a more financially prudent approach. By leveraging technology for targeted delivery, the Modi government has ensured that the benefits of its welfare schemes reach the deserving without creating an unsustainable fiscal burden. The emphasis has been on empowerment and creating assets – a house, a toilet, a bank account, a gas connection—rather than just providing handouts.

The greatest success of Narendra Modi lies in his audacious and successful effort to revive, strengthen, and expand the Indian welfare state, making it an engine of inclusive growth and a powerful instrument of political mobilization. By embracing technology, ensuring financial prudence, and maintaining a relentless focus on the needs of the poor, he has created a new model of welfarism that stands in sharp contrast to the failing systems of the West.

This has not only improved the lives of millions of Indians but has also forged a new political paradigm, one where good governance and the direct delivery of welfare are the ultimate keys to electoral success. The architect of this new welfare state has not just built schemes; he has built hope, dignity, and a new sense of empowerment for the people of India.

Modi’s greatest achievement as leader is remaking the Indian welfare state into a financially sustainable, inclusive, and effective pillar of national progress, uniquely balancing welfare expansion with fundamental economic discipline. This, far more than ideology or charisma, explains his enduring popularity and India’s burgeoning position in the global economy.

This is not to suggest that the task is over. Not by far. But if he wins in 2029, this would be the main reason.

The author is director of the Jindal India Institute of the O. P. Jindal Global University, and a professor.