While still relatively under-the-radar, this project is already facing the kind of pressures once applied to try and stop India’s nuclear programme. India must not relent.

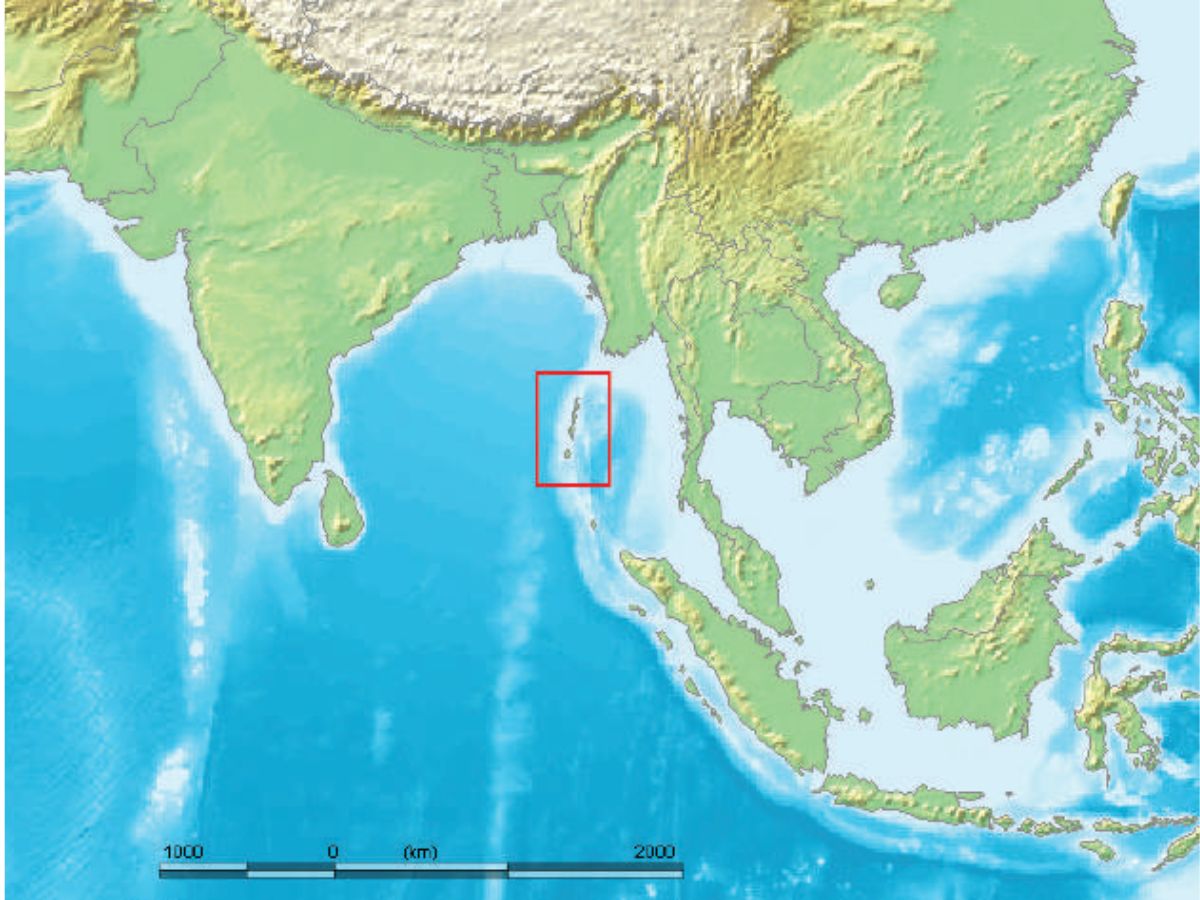

Location of Andaman and Nicobar Islands

The question of who controls which global maritime chokepoints and sea routes has been brought brutally on the table by US President Donald Trump’s demand for a handover of Greenland to American control. As Trump hopes to counter China in the northern sea routes, the crisis in the Bay of Bengal is deepening. Even as India moves ahead with its big Andaman and Nicobar development projects (especially the Great Nicobar Island project), the noise against the project from assorted activists, environmentalists, and even major political players is increasingly reminiscent of the clamour nearly three decades ago against India’s nuclear programme.

STRATEGIC ARCHITECTURE OF GREAT NICOBAR PROJECT

The Great Nicobar Island (GNI) project—conceived by NITI Aayog and launched in 2021—aims to create an International Container Transshipment Terminal (ICTT), a greenfield international airport, a township, and a gas-solar power plant, implemented by ANIIDCO. Strategically, official policy commentary frames this as dual-use infrastructure that can reduce reliance on foreign hubs like Singapore and Colombo while improving India’s ability to monitor sea lanes near the Malacca, Sunda, and Lombok Straits. The wider Andaman & Nicobar posture is anchored by the Andaman and Nicobar Command (ANC), India’s only tri-service theatre command, alongside bases such as INS Baaz and INS Utkrosh that expand surveillance and operational reach in the eastern Indian Ocean.

A major base-plus-port complex in the Nicobars changes peacetime “maritime geography” into wartime leverage: it strengthens India’s capacity to observe, track, and potentially interdict movements through approaches to the Strait of Malacca—one of the world’s busiest maritime chokepoints—thereby sharpening great-power threat perceptions. Indian strategic writing also notes that fortifying the ANC can intensify grey-zone competition and raise the spectre of blockade logics, which is exactly the sort of scenario competitors plan against in the Indo-Pacific.

Add to this a practical constraint: the archipelago’s ecological fragility and the GNI project’s environmental/tribal controversy create multiple handles (litigation, activism, international scrutiny, standards-based finance constraints) that can be amplified externally to slow or delegitimise the build-out. From Beijing’s perspective, stronger Indian air and naval reach in the Nicobars tightens the strategic environment around China’s energy and trade flows that pass near Malacca, deepening China’s long-running vulnerability to chokepoint pressure in a crisis. Indian policy commentary explicitly links Great Nicobar’s location to monitoring vital sea lanes and responding to rising presence of China and other navies in the Indian Ocean Region, signalling that the project has a balancing function—not only an economic one.

That combination—capability plus declared intent—makes it rational for China to lean into countervailing moves (surveillance, undersea presence, influence campaigns, competitive port access in the region) that would turn the project into an enduring strategic contest. The Andaman and Nicobar geography intersects with India’s sea boundaries in the Bay of Bengal neighbourhood, and Indian commentary notes the islands’ proximity to multiple regional maritime frontiers (including Bangladesh) and their role as a “first line of maritime defence.”

For Pakistan, any Indian shift toward an “unsinkable aircraft carrier” posture in the east adds to India’s ability to shape maritime domain awareness and power projection across the wider Indian Ocean strategic theatre, encouraging Pakistan to coordinate narratives and diplomatic positions that frame the build-up as destabilising. An “unsinkable aircraft carrier” refers to a land-based territory, typically an island or archipelago, leveraged as a fixed, durable platform for projecting air and naval power, much like a mobile aircraft carrier but immune to sinking.

For Bangladesh, the more likely friction point is not direct military competition but the politics of regional balance: Dhaka will be sensitive to anything that looks like coercive control of Bay of Bengal sea space, even if India frames it as counter-piracy, anti-trafficking, and sea-lane security. Separately, the most credible “American” constraint is often indirect: environmental and indigenous-rights scrutiny (including in global civil society and standards-driven capital) can constrain timelines and reputations—exactly because the islands are described as a globally significant biodiversity zone with vulnerable indigenous communities.

The maritime geography of the 21st century is increasingly defined by the transition of remote archipelagos from peripheral territories into central nodes of power projection. The Andaman and Nicobar Islands (ANI), a chain of 836 islands and islets stretching over 700 kilometres from Landfall Island in the north to Indira Point in the south, represent the most critical component of India’s nascent maritime grand strategy. Long termed “neglected maritime terrain,” these islands are now the site of the $10 billion Great Nicobar Island (GNI) Development Project—a mega-infrastructure initiative designed to integrate commercial transshipment, civil aviation, and tri-service military command. However, the strategic elevation of the ANI has catalysed a profound geopolitical reaction.

The GNI project, launched in 2021 under the aegis of NITI Aayog, is far more than a conventional infrastructure build-out; it is a force multiplier providing a permanent forward vantage point over one of the world’s most congested maritime chokepoints. The project’s placement at the southernmost tip of the archipelago positions it at the mouth of the Malacca Strait, through which approximately 25% of global maritime trade and 80% of China’s imported crude oil pass annually.

The development is structured around four primary pillars, each designed to function in a dual-use capacity, blending commercial viability with strategic depth. The International Container Transhipment Terminal (ICTT) at Galathea Bay is envisioned to rival the throughput of Singapore and Colombo, allowing India to capture cargo that is currently handled at foreign ports. By establishing a hub for ultra-large container vessels, India intends to achieve a level of maritime sovereignty that reduces its dependence on the logistical chains of potentially adversarial or unstable neighbours.

The military dimension is equally ambitious. The Andaman and Nicobar Command (ANC), established in 2001 as India’s only integrated tri-service command, is currently undergoing a massive upgrade to its airfields, jetties, and surveillance assets. The extension of runways at naval air stations like INS Baaz and INS Kohassa is specifically designed to accommodate long-range maritime patrol aircraft such as the P-8I Poseidon and advanced fighter jets. The second-order implication of this build-out is the creation of a persistent surveillance arc extending 1,200 kilometres from the mainland, covering the Preparis Channel, the Ten-Degree Channel, and the Six-Degree Channel.

KEEPING CHINA AT BAY

China views the fortification of the Great Nicobar as a direct threat to its national security, as it effectively places a “gatekeeper” at the entrance to the Malacca Strait. Beijing’s response has evolved from diplomatic protests to a sophisticated strategy of maritime encroachment, hybrid warfare, and underwater data collection intended to neutralize the Indian advantage. A primary mechanism of Chinese interference is the deployment of research vessels and survey ships across the Indian Ocean Region (IOR). Vessels like the Yuan Wang 5, Shi Yan 6, and Lan Hai 101 are officially designated for marine scientific research, yet their instrumentation—including advanced telemetry, bathymetric sensors, and acoustic processors—serves clear military purposes. In late 2025, the IOR witnessed one of the densest clusters of Chinese survey activity, with as many as five vessels active simultaneously near Indian missile test trajectories and strategic naval corridors.

The strategic prize for Beijing is data. High-resolution mapping of the ocean floor, salinity gradients, and thermoclines is essential for modelling the underwater environment to enhance the stealth of next-generation Type 096 SSBNs. By identifying acoustic channels and natural sound amplifiers, the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) aims to develop routes that allow its submarines to bypass the ANC’s surveillance sensors. Furthermore, Chinese survey ships have been observed lingering in regions where India has issued Notices to Airmen (NOTAM) for missile tests, likely to gather telemetry and acoustic signatures of Indian submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) like the K-4.

Beyond the sea, China has leveraged its “String of Pearls” strategy to establish logistical footholds that encircle the ANI. The reported development of signals intelligence facilities on Myanmar’s Coco Islands, located just 55 kilometres north of the Andaman chain, provides Beijing with a direct window into Indian naval movements. This proximity creates a persistent surveillance challenge for the ANC, forcing India to divert resources toward the northern reaches of the archipelago rather than concentrating solely on the southern chokepoints.

The strategic landscape of the Bay of Bengal underwent a dramatic transformation following the ouster of Sheikh Hasina in August 2024. Under the interim government of Muhammad Yunus, Bangladesh’s posture toward India has shifted from security cooperation to strategic recalibration, moving closer to a China-Pakistan-Bangladesh convergence that directly pressures India’s eastern maritime and land corridors. In this, perhaps the most significant development in 2025 has been the re-entry of Pakistan into the Bay of Bengal security space. For the first time in over 50 years, a Pakistan Navy frigate, PNS Saif, docked at Chattogram for a goodwill visit in November 2025. This was not an isolated event but part of a structured renewal of defence ties, including training cooperation and potential procurement of JF-17 Thunder aircraft from Pakistan.

The US has long sought military access to the ANI, viewing them as a pivotal strategic asset for monitoring the entry and exit points of the Indian Ocean. American strategists argue that the islands would be most valuable in the context of a broad coalition defending the maritime commons, often implying that Indian unilateral control is insufficient to deter a rising China. However, India remains deeply cautious of allowing a foreign superpower to establish a footprint on its most sensitive territory. The memory of colonialism and a commitment to strategic autonomy drive New Delhi’s preference for being a Net Security Provider on its own terms, rather than a junior partner in a US-led blockade of the Malacca Strait. The US push for integrating Indian sensors into the Fish Hook sound surveillance system (SOSUS) and gaining logistics access at ANI bases has frequently met with resistance from an Indian security establishment wary of Western-style militarism.

The GNI project is currently facing a sophisticated campaign of lawfare—the use of legal and environmental frameworks to stall or prevent infrastructure development. This opposition, while often framed around legitimate ecological and indigenous concerns, is increasingly perceived as a tool used by external forces to prevent the militarisation of the island, and to stop India from utilising and securing a critical domain. What happens next is probably rather than a single dramatic clash, the more probable flashpoint is a slow-burn competition: constant intelligence collection, legal-environmental obstruction, narrative warfare, and calibrated shows of force around sea lanes and island approaches. This will be intensified by physical risk: the Nicobar region’s seismic and tsunami exposure raises the cost of any large fixed infrastructure and increases crisis instability if a disaster intersects with strategic competition (evacuations, HADR operations, and military deployments happening simultaneously). The net effect is that the Great Nicobar/Andaman build-out becomes a permanent “contestable asset”—valuable enough to build, but also valuable enough for rivals to try to delay, discredit, survey, or operationally offset.

Hindol Sengupta is professor of international relations, and director of the India institute, at O. P. Jindal Global University