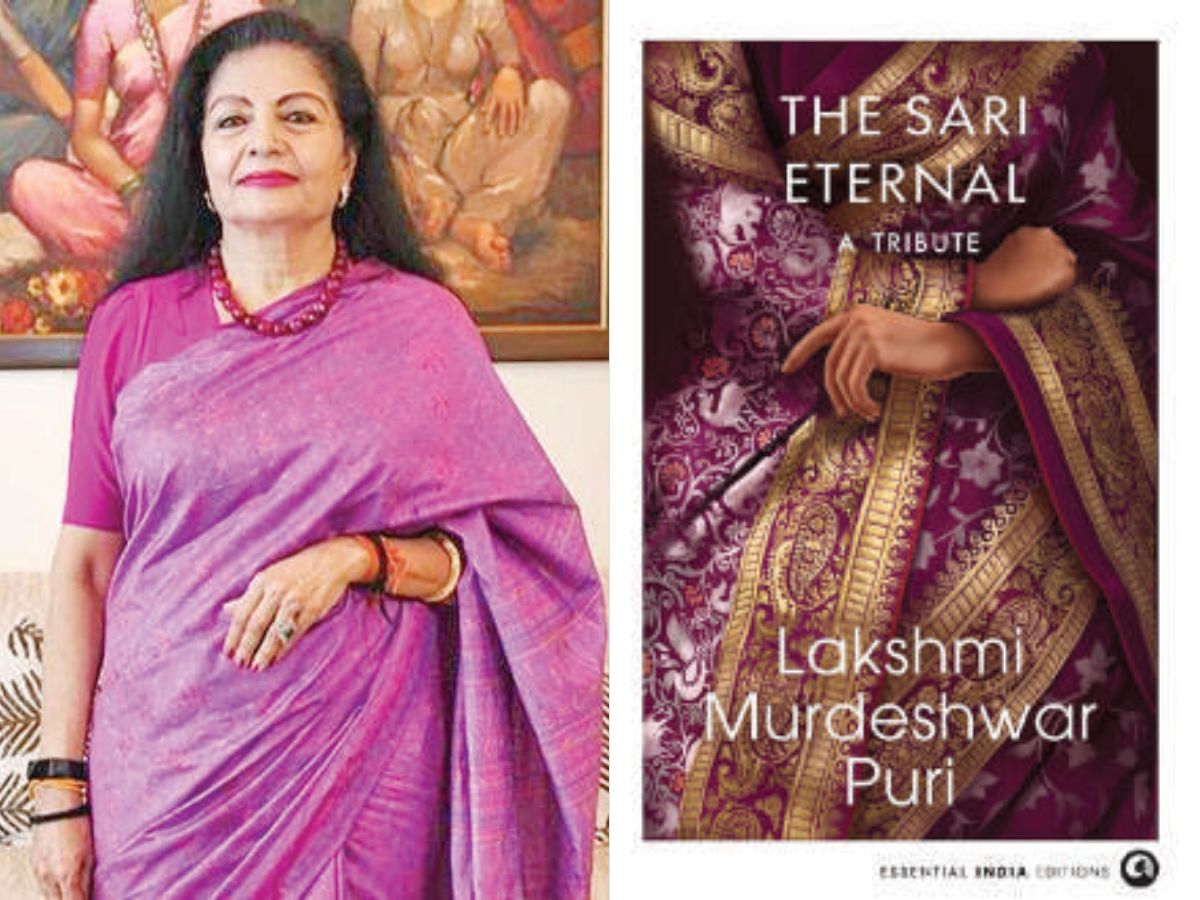

In her just released book, ‘The Sari Eternal’, the sari, for Lakshmi Puri, becomes a visual language, quiet yet assertive, through which India’s civilisational continuity is represented on global platforms.

Lakshmi Puri in a sari.

‘The Sari Eternal” is a dazzling gem—easy to hold, elegantly designed and finely chiselled, the book reflects the writer herself. Lakshmi Puri has written a personalised memoir of her own love affair with the sari: she has dared to encapsulate the vast universe of the sari in the palm of a book. It is a soaring ode and a tribute to it as much as a fervent and seductive invitation to Gen Z to take it into the future with confidence and aplomb. It is divided into chapters, each complete in itself.

It is the reflective afterword that captures the essence of the book. Each chapter functions as an independent, engrossing, meditation, yet together they form a continuous drape of memory, culture, and meaning.

This is definitely not the first book on the sari, nor is it the most definitive. Authors like Rta Kapur Chisti, Mukulika Banerjee, Jasleen Dhamija, Ritu Kumar, Malvika Singh, and Vandana Bhandari, among others, have written extensively on the subject. Rta Kapur Chisti’s “Saris of India” is a landmark work that meticulously documents drapes, techniques, and regional practices. Malvika Singh’s writings engage with the sari as a cultural and aesthetic statement, often within broader discussions of Indian identity and craft. Vandana Bhandari’s work foregrounds textile history and design evolution.

Yet “The Sari Eternal” occupies a markedly different register. In contrast to the other works, “The Sari Eternal” is neither classificatory nor analytical in the conventional sense; it is experiential, telling the story of the sari as only she can. Puri does not map the sari, she inhabits it. This isn’t an academic book on the six yards of textiles. There is mention of the many kinds of weaves, styles or materials used for the sari. It is evident that Laksmi took a conscious decision to create and share her own trajectory in writing this book. Her authority lies in memory, embodiment, and lived continuity rather than taxonomy.

From her personal engagement with the sari to creating her professional persona as a diplomat attired in the intricate warp and weft of the many threads and the subsequent tapestry woven to create the plural identity of the very diverse cultural landscape of India—for Puri, the sari becomes a visual language, quiet yet assertive, through which India’s civilisational continuity is represented on global platforms.

The book consists of six chapters: Sari Love, The Sari Eternal, The Sacred and the Mundane, The Sari in Epics and Classical Literature, The Bollywood Effect and The Future of the Sari. From the foreword of the book, each chapter reveals a new layer of emotional, historical, sacred, cinematic, poetic or speculative, while remaining grounded in personal narrative. Lakshmi begins by saying, “The sari. This unstitched river of fabric that winds around my body is not clothing; it is a second skin for me. I live in it, and it makes me whole, aesthetically and spiritually!” What a beautiful way to begin.

Puri’s engagement with the sari began with her mother, who had an overwhelming influence on her, who herself was a proud and loyal wearer of the sari. The sari, also a second skin to her mother. Through this inheritance, the sari becomes a vessel of tradition passed down not simply as fabric, but as value and worldview. The first chapter is entirely devoted to Lakshmi Puri’s personal relationship with the sari, her memories, her intimacy with the garment, and the way it has shaped her sense of self.

In the second chapter, Lakshmi Puri anchors the sari within a civilisational continuum by drawing upon ancient textual references, including the Vedic period, to different kinds of regional saris like Kanjivaram. The chapter is consciously anecdotal, allowing personal memory to serve as a bridge which makes the history surface organically through experience.

In the Sacred and the Mundane, Puri examines the sari as a sacred cloth through references to the Devi Suktam and the idea of feminine cosmic energy. She reads the sari through the symbolism of the Tridevi—Lakshmi, Saraswati, and Durga—positioning it as a sacred aavaran that simultaneously belongs to ritual space and everyday life. In doing so, the sari becomes a site where the divine feminine finds material expression.

The sacred rivers are envisioned as sari wearing Goddesses as are other elements of nature. She traces the evolution of the concept and vision of Bharat Mata in her sari-clad avatara too, pointing out how real life heroes have kept faith with and been empowered by the sari in different realms—queens, generals, social reformers, political, corporate and media leaders.

The chapter on epics and classical literature extends this inquiry into textual and visual culture, tracing the sari’s presence in myth and art, where it functions as both material and metaphor, signifying modesty, power, fertility, and sovereignty.

The Bollywood Effect examines the role of Indian cinema—both Hindi and that created by Satyajit Ray—in shaping popular imagination, showing how film transformed the sari into an enduring icon of desire, nationalism, nostalgia,, purpose and glamour.

The last chapter is reflective and forward-looking, engaging with questions of sustainability and modern identity, and envisioning the sari not as a relic, but as a living form capable of reinvention without losing its roots.

Throughout the book, Lakshmi brings together the tradition and modernity of fabric, culture, and apparel. She reflects on identity and on how the sari continues to function as an emblem or the iconography of the Indian woman: from Goddesses such as Lakshmi and Saraswati draped in saris, to Raja Ravi Varma’s paintings, and finally to her own mother’s lived experience, who only stopped wearing the nine yard sari when she came to Delhi at the age of fortyfive.

The movement from the personal to the historical, from anecdote to sacred reference, creates a cultural reading of the sari that is intimate and enticing, distinct from any other approach to the subject of textiles.

Dr Alka Pande is art historian, author & curator.