At a high-profile Delhi launch, M.J. Akbar redefines astrology’s role in Mughal governance.

The book highlights how celestial advice shaped imperial decisions and argues for recognizing civilizational heritage as a key to societal harmony.

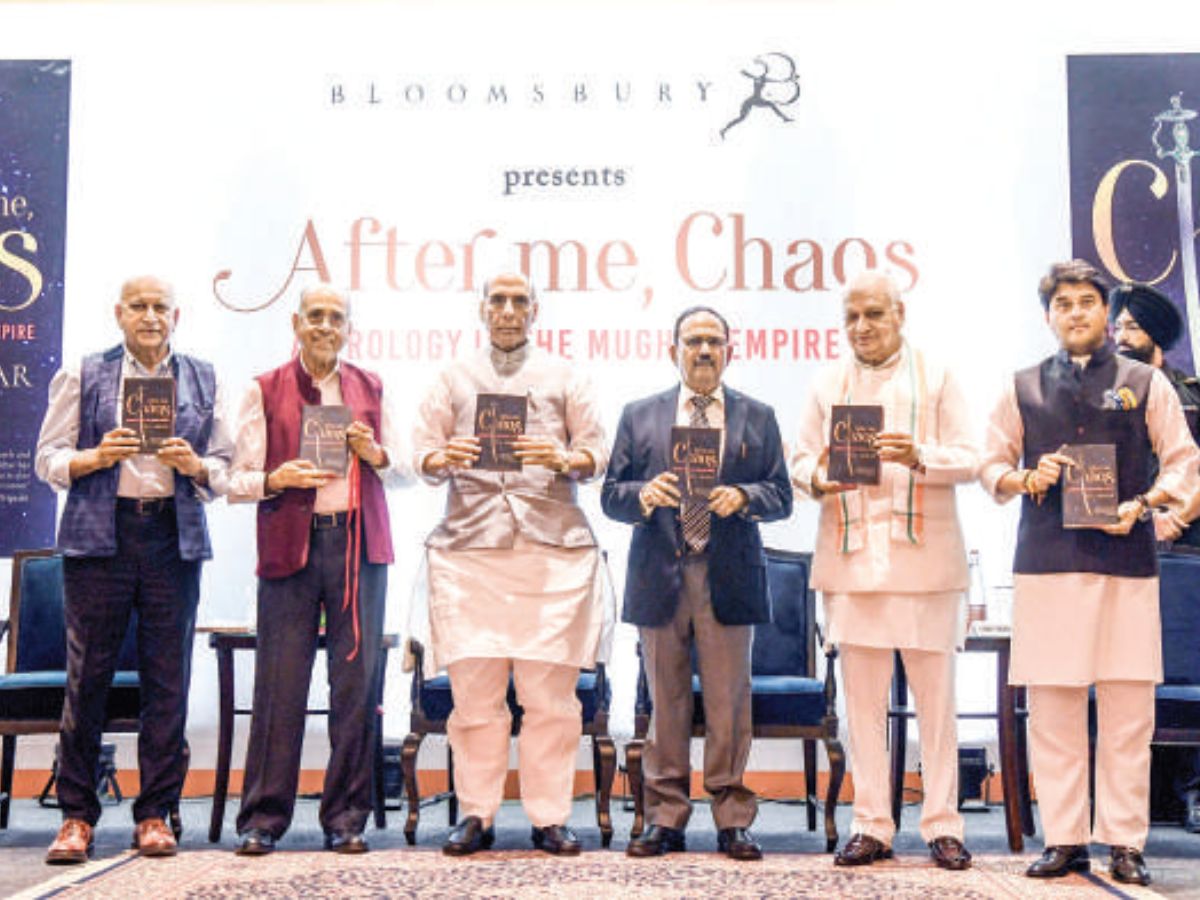

Veteran journalist and former Union minister M.J. Akbar launched his 12th book, After Me, Chaos: Astrology in the Mughal Empire, earlier this week in New Delhi. The event was attended by Defence Minister Rajnath Singh, National Security Adviser Ajit Doval, Union Minister Jyotiraditya Scindia, Bihar Governor Arif Mohammad Khan, and former Principal Secretary to the Prime Minister Nripendra Misra.

Akbar’s latest work challenges conventional historical narratives on astrology, arguing that the Mughal emperors’ deep engagement with it was not a mere personal fascination but a vital part of governance and statecraft. Drawing on original sources such as the Akbarnama and Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri, the book explores how celestial interpretation influenced key imperial decisions—from royal appointments to military campaigns. Akbar traces this tradition to the dynasty’s pre-Islamic cultural roots, linked to the lineage of Genghis Khan. The book sheds light on the intricate interplay between politics, power, and the planets, offering a fresh perspective on how astrology shaped the rise and eventual decline of one of the world’s most powerful empires.

Speaking at the event, NSA Ajit Doval praised the book, describing it as a detailed exploration of how major Mughal decisions were often taken after consulting astrologers. He lauded Akbar’s meticulous research and lucid storytelling. Doval said one of the book’s key revelations is Emperor Akbar’s institutionalisation of astrology in his court through the creation of the post of Jotik Rai—the royal astrologer—a position held for generations by Brahmin scholars from Benares. These astrologers were often lavishly rewarded, sometimes with gold and silver equal to their own weight, underscoring the emperor’s deep reliance on their counsel.

Doval added that M.J. Akbar recounts several pivotal historical moments shaped by astrological advice. When Humayun was a fugitive, receiving his son Akbar’s horoscope rekindled his hope for reclaiming the empire. Years later, Akbar undertook a risky campaign in Kashmir in 1586, guided by his astrologer’s counsel despite opposition from his generals.

At the launch, Rajnath Singh shared a passage from Akbar’s book describing how Emperor Jahangir saw a bullet-shaped comet before Aurangzeb’s birth—an omen he found disturbing. Akbar connects this and another celestial event as metaphors for the fall of Dara Shikoh and Aurangzeb’s rise to power. Despite Aurangzeb’s rigid rule and intolerance, Singh noted, his influence on history remains monumental. The Defence Minister highlighted that Aurangzeb himself had foretold the fate of his empire—a reflection that inspired the book’s title, What Will Happen After Me? Singh said the book not only captures historical detail but also demonstrates the timeless power of astrology. He emphasized the interconnectedness of the universe, likening it to the “butterfly effect,” where even small actions can create vast consequences. “Just as politics needs philosophy,” he said, “science too needs spirituality to remain grounded.”

Recalling India’s ancient wisdom, Singh noted that disciplines like mathematics, astronomy, and astrology—collectively known as Jyotisha—were once viewed as a single branch of knowledge. He cited the example of Lord Buddha, whose horoscope predicted he would become either a great ruler or a spiritual guide—a prophecy that proved true. Concluding his remarks, Singh said astrology honours karma, not luck. Quoting the Bhagavad Gita, he reminded that while the stars may guide, destiny is shaped by one’s actions. Even great sages like Vasishtha, he said, could not change fate, yet their teachings remind us that destiny is not despair—it is a call to act. “Our greatest power,” Singh said, “lies in our karma and in fulfilling it with purpose.”

M.J. Akbar reflected on the intersection of rationality, faith, and astrology, arguing that belief in astrology need not be irrational. He said true progress begins with doubt and an open mind, not denial. “Why should knowledge be limited to what we already comprehend?” he asked, emphasizing that much of the human mind and universe remains unexplored. He traced astrology’s roots to ancient Indian and Jain traditions, highlighting how the Mughals assimilated these ideas into their worldview. Akbar argued that societies acknowledging their civilizational heritage before religion tend to be more harmonious, whereas denying it—as in Pakistan’s case—leads to dysfunction.

He recounted stories showing how belief in planetary influence shaped events, such as prophecies surrounding royal births. Akbar lamented how later rulers like Aurangzeb and colonial powers disrupted India’s cultural unity by dividing history along religious lines. He concluded that India’s strength lies in its civilizational synthesis—the blending of cultures, languages, and philosophies—and urged all communities to rediscover that shared cultural foundation, remembering that culture is older and deeper than religion.