Over 2,500 years ago, the kingdom of Magadha in the Gangetic plains rose to prominence by embracing new technology. Magadha had iron ore deposits and smiths, enabling better tools and weapons. Iron axes cleared dense jungles for farms, yielding agricultural surpluses. Iron swords and elephants gave Magadha a military edge. Magadha’s society was relatively unorthodox and inclusive for its time, which made it more receptive to innovation and expansion than more rigid neighbours. An open-minded culture combined with superior know-how allowed this once minor mahajanapada to defeat older oligarchies and build one of ancient India’s first empires. The lesson? A civilization that welcomes new techniques and ideas—rather than clinging to old habits—gains a decisive advantage.

Congratulations to Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt, winners of the 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics for their work explaining how innovation and “creative destruction” drive economic growth. Their research shows that new ideas—technological and otherwise—spur new products and methods which replace old ones, lifting living standards. They warn that progress cannot be taken for granted: stagnation, not growth, has been the historical norm, and only by defending the conditions that allow innovation can we avoid slipping back.

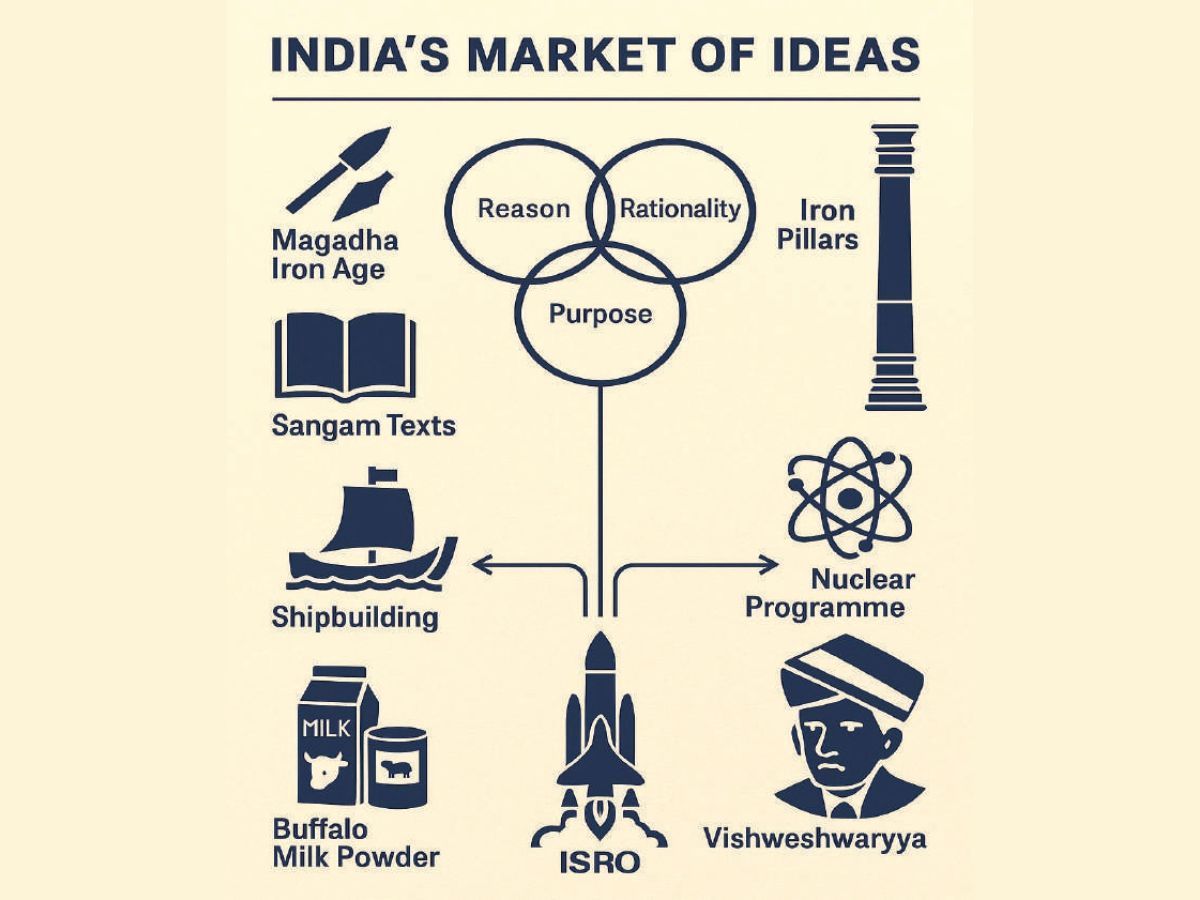

This insight holds relevance for India. Our future prosperity hinges on cultivating a “market of ideas”—a free, competitive arena in every field from economics and engineering to media and the arts—on dismantling the oligarchies and monopolies that smother fresh thinking.

What exactly is a “market of ideas,” and why does it matter? Mokyr’s historical work illustrates that Europe’s rapid progress since the Enlightenment was no accident—it emerged from an open intellectual culture often called the Republic of Letters, a kind of competitive marketplace for ideas. In this arena, no authority could unilaterally silence a new theory and no “inviolable idea” existed—no belief was beyond challenge. Just as economic theory tells us free entry yields better outcomes than monopoly, the free entry of new thinkers and dissenting ideas produces a more salutary result than enforced orthodoxy. When thinkers are free to “propose theories, facts, observations” and compete to persuade others, knowledge advances and society reaps the rewards in technology and prosperity.

Oligarchies and monopolies—whether in business, politics, or culture—act as high walls around this marketplace. They choke off the competition of ideas. In a healthy economy, new firms continually rise and old ones fall. This churn isn’t chaos; it’s vitality. Each incumbent’s success motivates challengers with even better ideas to “climb to the top of the ladder”, unseating yesterday’s winners. The cycle drives progress. But if incumbents entrench themselves, using power to block newcomers, the cycle breaks—innovation slows and society stagnates.

Aghion himself, in accepting the prize, cautioned against allowing giant firms to dominate. “Some superstar firms may end up dominating everything and inhibiting potential entry of new innovators. So how can we make sure that today’s innovators will not stifle future entry and innovation?” he asks. The Nobel Laureate’s message echoes the ideals of the Enlightenment—reason, openness, and the courage to upend old ways. Mokyr’s work identifies openness to change as a key prerequisite for sustained growth.

Why? Because every innovation threatens someone’s privilege. New technology creates winners and losers, and those who stand to lose will try to block change if they can. In Europe, the Enlightenment eroded the ability of privileged guilds and lords to halt progress. Parliament and public debate made it harder for any one faction to declare an idea off-limits. This institutional openness meant inventors and entrepreneurs could freely experiment, knowing that vested interests would find it harder to crush their nascent innovations. “A society open to change” removed a major barrier to growth.

The Sangam literature, composed by poets of diverse backgrounds, paints a picture of an Indian society engaged with the wider world. To this day, in Delhi, a 1,600-year-old iron pillar stands untouched by rust, defying the entropy of time. Forged in the Gupta era around 400 CE, this pillar’s corrosion resistance is not magic but the result of advanced metallurgy—a precise high-phosphorus iron mix and a skilful forging technique. The pillar, likely a celebratory column of victory, also hints at something deeper: iron in India was not a craft secret locked up by guilds; it became widespread practical knowledge.

Progress comes from openness—to new technology, to foreign contact, to challenges against tradition—and stagnation sets in under closed, insular, or monopolistic conditions. When India’s culture has been liberal and venturesome, we have been world leaders; when we’ve yielded to inward-looking orthodoxy or let a few elites dictate the boundaries of thought, we’ve fallen behind. Openness and competition in ideas are not just relics of ancient glory; they are alive in modern India’s successes—often despite resistance from the status quo.

Consider two examples. Not long after Independence, India faced a challenge in infant nutrition. Against scepticism, scientists and industrialists pioneered a method to produce high-quality baby milk powder from buffalo milk, a world first. Would such an idea emerge in a system dominated by a few big foreign multinationals or hidebound bureaucrats? It emerged because a culture of scientific freedom was fostered—a legacy of visionaries like M. Visvesvaraya and Homi Bhabha who believed India could do original R&D. We must continue to protect and expand that freedom for innovators, so that propositional ideas (the fundamental scientific insights Mokyr talks about) are generated here, not just prescriptive knowhow borrowed from abroad.

Too often, India has been content to scale up formulas handed down from the developed world, without investing in our own bluesky research—a symptom of intellectual complacency and deference to authority. In the 1960s, our scientists hauled parts of the first rockets on bicycles and bullock carts. Fast forward to 2023: India became the first country to land near the Moon’s south pole. ISRO’s story is creative destruction in action: old assumptions about “a poor country can’t do space” were destroyed by evidence of what is possible.

We must demand that the same openness and vision apply in other spheres—let new startups challenge giant firms without unfair hurdles, let new artists and writers challenge Bollywood formulas and political taboos, let young policy thinkers challenge entrenched ‘expert’ dogmas.

The thread running through all these tales—from ancient Magadha to modern Moon missions—is liberty. By liberty, we mean the freedom for individuals to think, speak, experiment, and enterprise without fear of undue sanction or domination. A market of ideas cannot function if an overlord can shut down the dissenters and upstarts at will. Where new ideas threaten old powers, the old powers often fight back—but enlightened societies choose to back the ideas over the privileges.

Our policymakers should aim to be enablers of the new. That means pruning away needless regulations, patronage networks that shield incumbents from competition. It means ensuring our education system encourages questioning. It means celebrating the iconoclasts, risk-takers rather than safe, status-quo followers.

With more freedom and less fear, India’s tryst with destiny can yet become a triumphant reality—a lesson that runs through the theme of the Bhagavad Gita as well.

Pooja Arora is Assistant Professor, Jindal School of International Affairs.