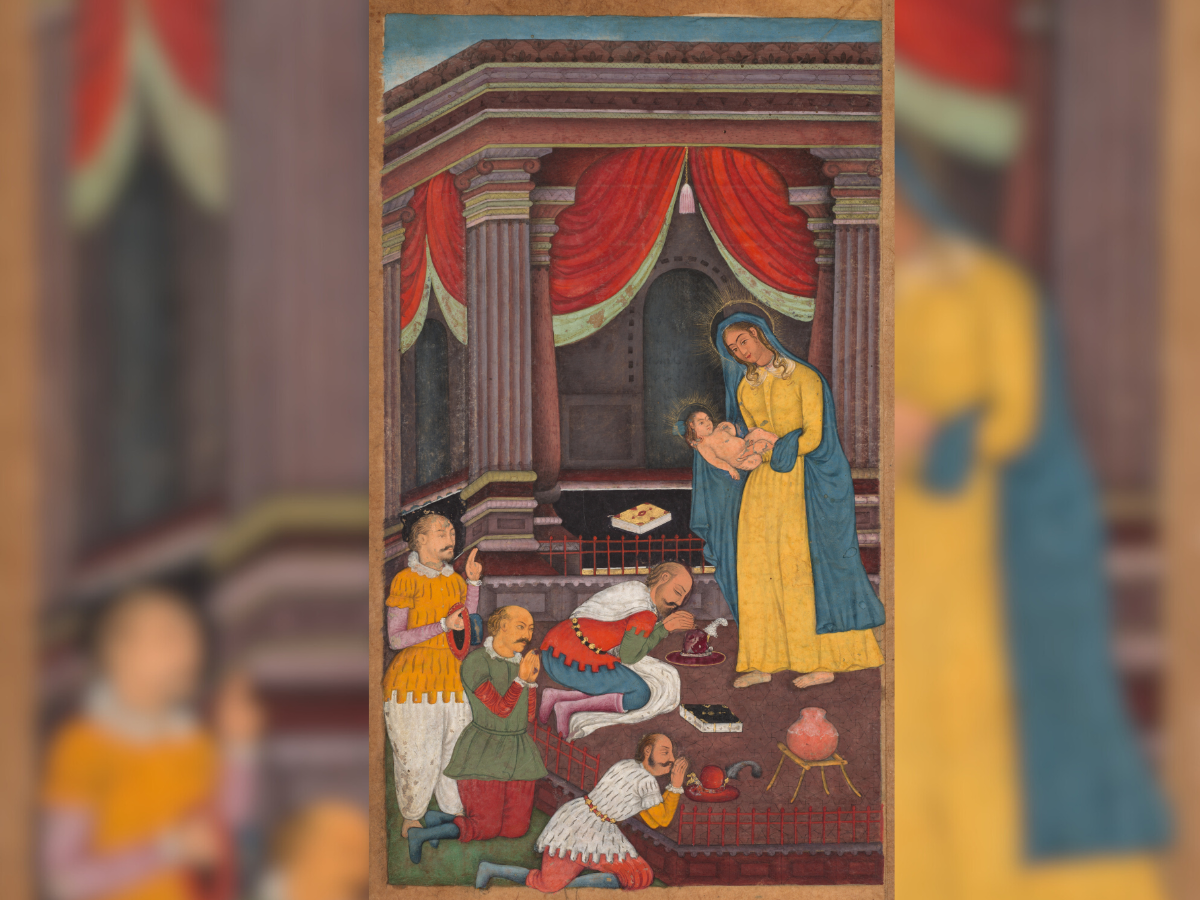

Fig. 2: Unidentified artist, The Madonna and Child, after Durer, early 17th century, watercolor on paper, 12.0 x 7.1 cm (The Royal Collection Trust, London); Fig. 3: Albrecht Dürer, Madonna by the Tree, c. 1513, engraving, 11.7 x 7.4 cm (The Royal Collection Trust, London)

Among the Christian subjects represented in Indian paintings, images of the Virgin and Child are amongst the most popular. From the Mughal imperial ateliers to Rajput courts, this pictorial depiction recurs with a familiarity that suggests more than passing curiosity. Why did this subject, in particular, resonate so strongly with Indian patrons and painters?

Indians have long held a cultural affinity for the image of the mother and divine child. Our lores are shaped around this bond - whether it is Yashoda and Krishna, Maya and the Buddha, or Trishala and Mahavira, the iconography of the nurturing mother occupies a central place in the Indian imagination. Moreover, Mary is revered within Islamic tradition as a model of piety and virtue- and mentioned in the Qur’an more frequently than in the New Testament. Mary, alongside Jesus (Isa), already occupied a respected place within Mughal religious thought.

During the reign of Akbar, Jesuit missionaries, along with European travellers, diplomats, and merchants, brought with them engravings and prints depicting Biblical subjects. These unfamiliar images piqued curiosity and, from the late 1580s, began circulating within the Mughal cultural sphere. These images introduced Mughal artists to Christian iconography—haloes, angels, cherubs, the Madonna, and Christ himself—at a time when Akbar was increasingly interested in learning about other religions and belief systems.

Jesuit sources recount that in 1602 the fathers exhibited, in the chapel in Agra, a lifesize painting of Madonna and Child, which created such a commotion that Emperor Akbar asked them to bring it to his palace for viewing. In his chronicle Relaçam, Father Fernão Guerreiro writes that Akbar came down from his throne, examined the picture closely, and “took off his turban half to show it his deep reverence.” That same year, Akbar commissioned the Jesuit priest Jerome Xavier to compose the Mirat al-quds (Mirror of Holiness), a Life of Christ written specifically for the emperor and illustrated by Mughal artists (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: The Adoration of the Shepherds, from a Mirror of Holiness (Mir’at al-quds) of Father Jerome Xavier, 1602– 4. Mughal The Cleveland Museum of Art

Under Jahangir, the Mughal engagement with Christian imagery took on a more formal and image-centric approach. Jahangir displayed a strong interest in faithful reproductions of European engravings, particularly those depicting Christ, the Virgin, and Christian saints. His insistence on close imitation suggests a belief in the talismanic power of images, valuing them as sacred forms (Bailey, 1998, p.30). This precision led approach is evident in works associated with the so-called Berlin Album of Jahangir, which includes adaptation of Albrecht Dürer’s Virgin under a Tree (1513) (figs. 2 and 3).

Fig. 2: Unidentified artist, The Madonna and Child, after Durer, early 17th century, watercolor on paper, 12.0 x 7.1 cm (The Royal Collection Trust, London); Fig. 3: Albrecht Dürer, Madonna by the Tree, c. 1513, engraving, 11.7 x 7.4 cm (The Royal Collection Trust, London)

This imagery stuck around and continued to be reinterpreted even when the Mughal court had considerably weaker rulers in the 18th century. Taking earlier engravings and paintings as reference, artists at the imperial centre and provincial courts, both took an interest in the subject (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4: Unidentified artist, The Madonna and Child, circa 1760, Awadh, (Private Collection, Delhi)

Christian imagery also reached the Deccan through European prints, despite the absence of documented Jesuit missions to courts such as Ahmadnagar or Bijapur. These interpretations are executed in a distinctly Deccani technique, with figures and forms modelled through confident, rhythmic lines (Fig. 6).

Fig. 7 : Ahmed, son of Shah Muhammad, Mother and Child, 1804, Bikaner, (Private Collection, Delhi)

The Rajput courts mark another stream of how this imagery was reproduced. Among these courts, Bikaner emerged as a particularly important centre for the reinterpretation of Christian subjects. Bikaner artists were long exposed to Mughal culture and models due to the court’s political alliances with the mughal centre, adapted Christian imagery with sensitivity and innovation rather than direct imitation. Paintings and prints may have entered the royal collection through diplomatic exchange, commissions, or war booty.

One of the most compelling examples is the painting we began with; dated 1804 from Bikaner, depicting the Virgin and Child in a thoroughly Indianised form (Fig. 7). Mary stands dressed in a bright green odhni and a purple garment patterned with gold bhuttas, adorned with Indian jewellery, and rendered with black hair rather than the golden hues of European Madonnas. The infant Jesus, having golden hair to show his foreign origins, is similarly assimilated—clothed in Indian dress, wearing a small turban, and holding a rattle.

Brought to India by Jesuit missionaries, the Virgin and Child was adapted and absorbed in India into a form that became familiar and local. As Christmas draws near, these images are a testament to how traditions travel and how beautifully they can belong.

Jayesh Mathur is an architect, independent scholar, and Indian art collector.

Supriya Gandhi is a museum professional and art consultant