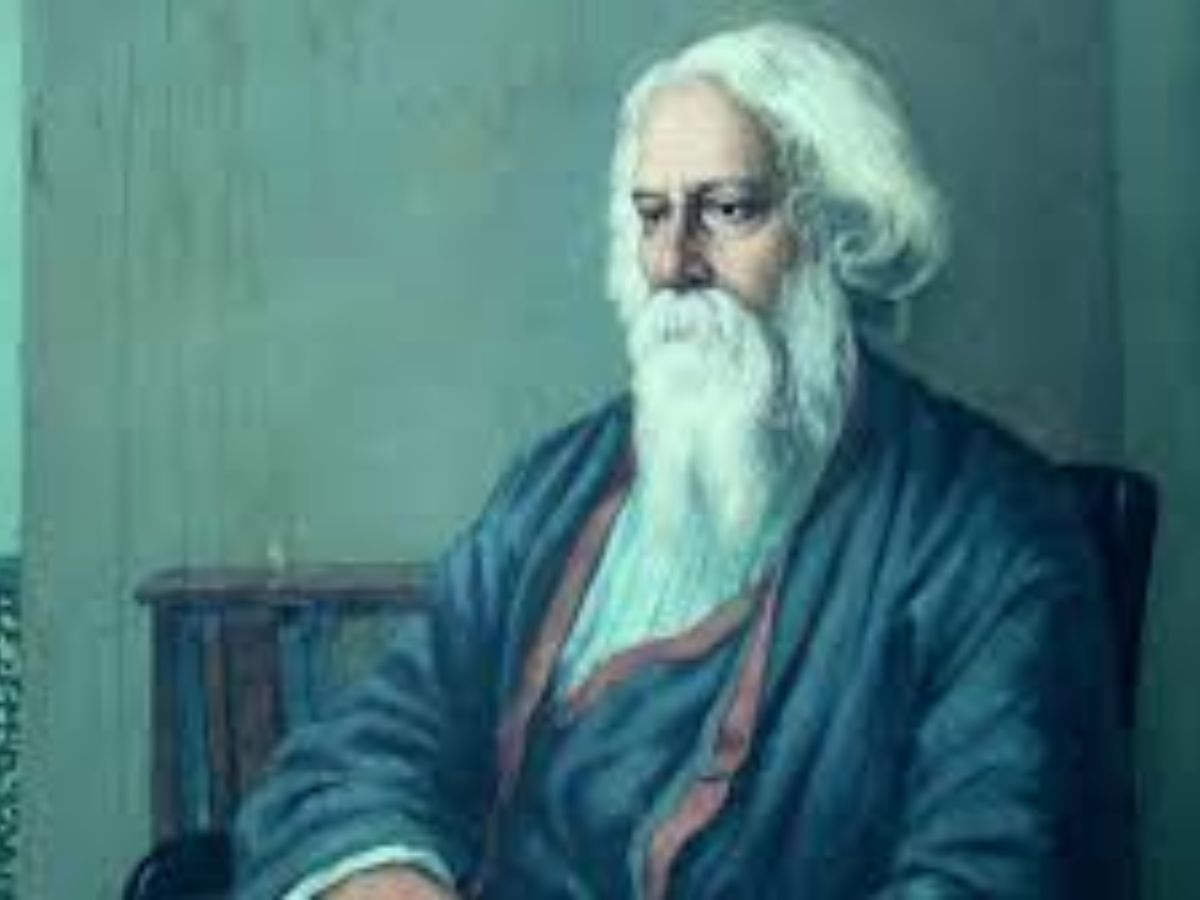

Rabindranath Tagore’s timeless vision of peace resonates powerfully amid today’s global turmoil.

Hingsay unmatto prithw, nityo nitthur dwando; Ghor kutilo pantho taar, lobhojotil bandho.

The world today is wild with the delirium of hatred. The conflicts are cruel and unceasing in anguish. Crooked are its paths, tangled its bonds of greed.

Written in 1927, these words of Rabindranath Tagore echo in the headlines of today. Close to a century later, turbulence continues to surge through the globe, leaving destruction and distress in its wake. Even as leaders propose solutions and seek resolution, peace remains an elusive chimera.

Tagore’s lifetime was marked with unprecedented global violence. He witnessed the horrific impact of two World Wars and lived through the Partition of Bengal in 1905, an event marked by violent sectarian riots. Tagore attributed this ongoing violence to three intersecting forces: the aggressive materialism of modern society; belligerent nationalism; and institutionalized religion.

Tagore believed that the absence of war did not necessarily mean the prevalence of peace; rather, war was the logical consequence of unmediated materialism, of science divorced from spirituality. In an article published in The New York Times in 1916, he wrote, “The war, to my mind, is the outcome of overgrown materialism, of an ideal based on self-interest and not based on harmony. There are differences between capital and labour because both are working in the interest of their own selves—peace is but temporary, and other clashes are bound to come.”

Tagore viewed nationalism as a source of war, especially the First World War. He considered nationalism the political arm of modern industrialised society. In his essay Nationalism, he writes that nationalism was not “a spontaneous self-expression of man as social being” but a political and commercial union of a group of people to maximise their profit and power. In A Cry for Peace, he said, “It is the national and commercial egoism, which is the evil harbinger of war.”

Strongly critical of organised religion, Tagore denounced it as a source of cruelty, oppression and violence. For Tagore, true worship lay outside the realm of ordained religion. In Verse 11 of the Gitanjali, he wrote: “Leave this chanting and singing and telling of beads! Whom dost thou worship in this lonely dark corner of a temple with doors all shut? Open thy eyes and see thy God is not before thee! He is there where the tiller is tilling the hard ground and where the path maker is breaking stones. He is with them in sun and shower, and His garment is covered with dust. Put off thy holy mantle and even like Him come down on the dusty soil!”

Despite what he witnessed in his lifetime, Tagore’s abiding optimism took spiritual shelter and refuge in humanity. His unceasing efforts to bring back peace and harmony through inter-civilizational dialogue and human fraternity were remarked upon by contemporaries such as Bertrand Russell, Albert Einstein, and Romain Rolland.

Tagore promulgated a vision of peace through the cultivation of the ideologies of Ahimsa, or non-violence, and Advaita, or one-identity of the universe. For Tagore, the antidote to violence was to recognise the Universe within the Self and to further recognize the Self within the Other. Blurring the lines between “me” and “you,” Tagore envisioned the creation of a global human community.

In a letter to Charles Andrews, written from Kashmir, India, Tagore wrote: “The first stage towards freedom is the Santam, the true peace, which can be attained by subduing self; the next stage is the Sivam, the true goodness, which is the activity of the soul when self is subdued; and then the Advaitam, the love, the oneness with all and with God. Of course this division is merely logical; these stages, like rays of light, may be simultaneous or divided according to the circumstances, and their order may be altered, such as the Sivam leading to Santam. But all we must know is that the Santam, Sivam, Advaitam, is the only goal for which we live and struggle.”

In his message to the delegates at the World Peace Congress held in Brussels in 1936, Tagore emphatically stated, “We cannot have peace until we deserve it by paying its full price, which is that the strong must cease to be greedy and the weak must learn to be bold.” How will this greed cease? How will this learning come about? It is in this context that we can explore Tagore’s educational project at Santiniketan, Sriniketan, and Viswabharati which were envisioned with the goal of seeking confluence.

Tagore’s philosophy of education was centered on two core principles—Maitri or friendship and freedom. According to Tagore, maitri encompassed inter-related relationships of friendship: relations between cultures, between human beings, and between human beings and nature. For Tagore, the learning environment also needed to embrace freedom—freedom of the mind, body, and spirit such that children could actualize themselves and develop to their full potential. Underlying the idea of freedom was self-restraint through inner realization. Through inculcating a love for art, music, literature, and nature, Tagore envisioned a community of socially responsible learners engaged in the pursuit of serenity and service, enabling a culture of peace while abrogating a culture of violence.

Norwegian sociologist and founder of peace and conflict studies Johan Galtung points out the relational nature of peace and distinguishes between ‘negative peace’ and ‘positive peace’. ‘Negative peace’ refers to the absence of violence. ‘Positive peace’ refers to the restoration of relationships, the creation of social systems that serve the needs of the whole population, and the constructive resolution of conflict. In a world sundered by violence, Tagore’s analysis of its underlying causes is relevant even today. His thoughts on actively working towards peace through education and social reconstruction offer a vision of hope for the future.

Ranu Bhattacharyya is an educator, dancer, Tagore scholar, and author of “Castle in the Classroom.”