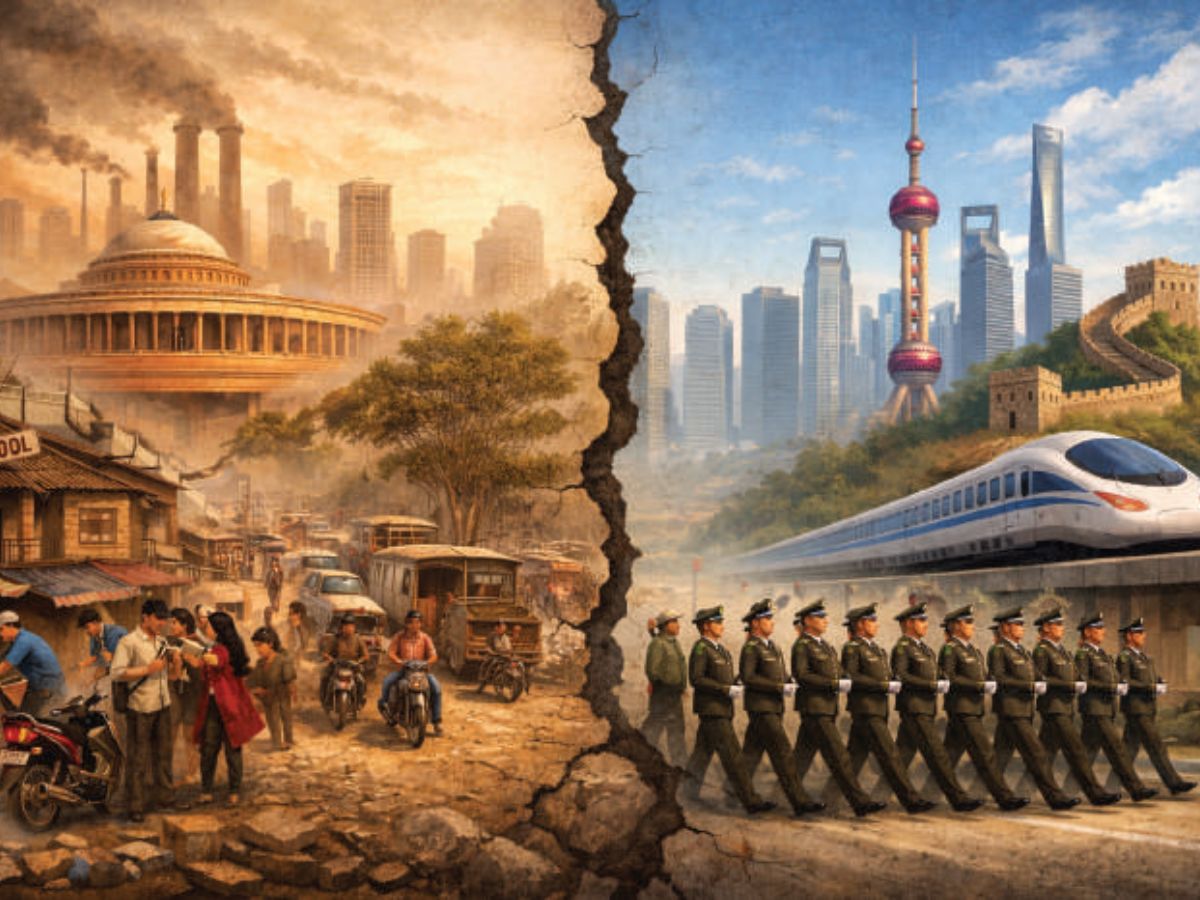

From comparable beginnings, India and China’s economic trajectories sharply diverged over the decades.

Unconscious democracy: Why order eludes India while China surges

Two nations entered the 1990s as poor economies. In fact, India was ahead of China in per capita GDP until the mid-1980s. By 1990, they were roughly equal. Today, the gap is stark. China’s economy stands at around $18-19 trillion; India remains at $4 trillion. The Chinese citizen is five times wealthier. To worsen the contrast, income inequality is lower in China than in India.

On almost all measures of material progress, China is well ahead. The average Chinese worker is two-and-a-half times more productive than the average Indian worker. China spends 2.6 percent of GDP on research and development; India spends around 0.6 percent. Chinese applicants file 16 lakh patent applications a year; India has only recently crossed one lakh. On law and order, India’s murder rate is four times China’s. The education gap may be the most telling. India’s literacy rate hovers around 77 percent; China has achieved near-complete literacy. But even our 77 percent flatters us. Literacy in India often means the ability to sign one’s name, not the ability to read a paragraph and grasp its meaning, not the ability to evaluate a claim against evidence. We count heads, not comprehension.

In 2009, the Programme for International Student Assessment tested both nations. China topped the tables. India’s two-state sample ranked second-last, barely above Kyrgyzstan. Over eighty countries now participate. India has never returned, repeatedly deferring re-entry, including stepping away from the planned 2022 cycle. Rather than confront what the mirror showed, we stopped looking.

On energy and climate, China leads the world in wind, solar, and hydro. Last year, China installed more renewable capacity than more than half of the rest of the world combined. India still builds coal-fired power plants. On infrastructure, manufacturing, state capacity, execution speed: any honest comparison ends the same way.

Consider the countries that climbed dramatically in this same era: Japan, Singapore, Taiwan, South Korea, Malaysia, Indonesia, even Israel. Their policy mixes differed, their politics differed, their histories differed. Yet one foundation keeps appearing: mass schooling that works, literacy that becomes comprehension, and public habits that reward evidence over impulse.

These are not merely economic differences. They describe a civilisational divergence. The usual explanation will not suffice: India chose democracy, China chose authoritarianism. But this framing obscures more than it reveals. Democracy versus authoritarianism is like asking: which disease should I choose? The physician will say: choose health. The real distinction lies elsewhere, between conscious freedom and unconscious freedom. What India has built is an unconscious democracy, where citizens possess the right to choose without the wisdom to choose well. Democracy was never the problem. Unconscious democracy was.

The Mundaka Upanishad speaks of two kinds of knowledge: the lower, which multiplies information, and the higher, which liberates the knower from illusion. Put in non-sectarian terms, the distinction is plain. One kind of education gives skills, data, and employability. Another gives self-knowledge: the ability to watch fear, greed, and identity at work, and not be driven by them.

A democracy providing only the first kind, without the second, will produce citizens who vote from bondage rather than understanding. They have the power to choose but not the light to see by. They can read the ballot but not their own minds.

What we call progress, GDP, infrastructure, innovation, is never purely external. It is driven by something internal. Roads, factories, and ports require order. Order is not merely policing. Order arises from minds that can restrain impulse, honour facts, keep promises, and cooperate beyond tribal identity. The chaos we see outside begins inside.

When higher wisdom is absent, freedom produces noise, not order. The voter who does not understand the vote’s implications, the consumer who cannot distinguish need from manufactured desire, the citizen who mistakes prejudice for principle: all exercise freedom while producing chaos. They choose, but do not know who is choosing. The machinery operates on autopilot. We keep pressing new buttons on the same old machine.

Consider the contradiction haunting every household. The same person demanding accountability as citizen demands indulgence as consumer. The same mind speaking of national progress fills its home with unnecessary purchases. The voter and buyer inhabit one body wanting opposite things: discipline from others, gratification for oneself. On the road we demand rules, yet we jump signals when it suits us. We rage at corruption, yet we normalise small bribes as convenience. We share forwarded certainties, then complain that society has become irrational. The disorder is not only in the system. It is in the one operating it. Until that one asks, “Who am I, and what do I really want?”, no ballot box will save us.

China built enforced collective discipline. External order was imposed where internal order was lacking. The achievements are real and extensive: factories that work, trains that run on time, infrastructure that executes at speed, research that produces patents, and a state apparatus that can mobilise at scale. Enforced discipline has delivered what unconscious freedom could not.

Yet enforced discipline is not the answer. It merely mirrors what unconscious freedom lacks. The Chinese model costs surveillance, suppression, the coercion of speech, and deep vulnerability for minorities. A nation disciplining citizens through fear has not solved unconsciousness. It has frozen it. The citizen under authoritarian control does not awaken; he merely obeys. His greed and fear remain intact, only their expression is regulated. Greed remains greed, even when it builds solar panels. Authoritarianism is not the cure for unconscious democracy. It is a different disease. The answer to partial freedom is not zero freedom. It is complete freedom, which means inner freedom.

And what of our own magnificent Constitution? Article 15, Article 19, Article 21: that entire stretch of fundamental rights ensures no external force can enslave you. The founders gave us protection from emperors, landlords, and priests. But here is what the Constitution cannot do: it cannot protect you from yourself. What if your desires, fears, prejudices, and false identifications keep you in bondage more effectively than any tyrant could? External freedom was given; internal freedom was assumed. That assumption has proven costly.

Fear is internal bondage. Greed is another. Attachment to images of caste, region, religion: chains no law can break. The Constitution can restrain the tyrant outside; it cannot touch the tyrant within. The man not knowing his own mind uses his vote to strengthen prejudice, and believes he is exercising choice. The woman not understanding her desires uses purchasing power to deepen emptiness, and calls it freedom. Freedom given to someone not knowing its meaning becomes a weapon against the self. The prisoner paints his cell in party colours and calls it conviction.

India built temples of higher learning, the IITs, the IIMs, while neglecting the foundation on which temples must stand. A poorly educated population cannot exercise freedom intelligently. It becomes susceptible to manipulation, identity politics, and promises aimed at fear rather than reason. The politician dividing on caste, region, or religion is not an aberration. He is the natural product of a democracy that distributed votes without distributing understanding. A population of children elects whoever promises sweets.

The question “Who am I?”, not as metaphysics but as practical self-inquiry, must enter curricula. The child is born with bondages inherited from family, culture, and biology. If education does not help identify those bondages, what freedom will the adult have? One cannot rely on the family to provide this wisdom; parents often lack it even for themselves. It must be a formal, non-sectarian exploration of the self, alongside rigorous training in reading, reasoning, and evidence. Without such education, we keep producing graduates who can code but cannot think, who can consume but cannot question, who can vote but cannot see.

In a nation of astonishing diversity (linguistic, regional, religious, caste-based) what can hold us together? Not shared mythology, for mythologies differ. Not shared language, for languages multiply. Politicians know this, which is why it is easier to win by dividing than by uniting. Only a shared discipline can unify: facts placed above identity, evidence honoured above emotion, and the courage to revise one’s position when truth demands it.

Those who fought for independence envisioned awakened citizens capable of self-governance in the deepest sense: governance of the self by the self. We achieved freedom’s external apparatus. What remains is inner work. History keeps turning its pages; the reader remains untrained. We upgraded the system while the one operating it remained untouched.

This is the only revolution that has not yet been attempted. India needs not less democracy but democracy beginning within. Teach the child to read, to reason, and to watch the self that wants. When freedom becomes inner reality, when citizens recognise their bondages and begin dissolving them, then external freedom produces the order, progress, and unity that have so far eluded us.

The Constitution gave us the vote. Now we must earn the wisdom to use it.

Acharya Prashant is a teacher, founder of the PrashantAdvait Foundation, and author on wisdom literature.