In China’s media landscape, censorship often works silently. Editors, guided by “stability” directives, routinely soften stories or erase key details before publication.

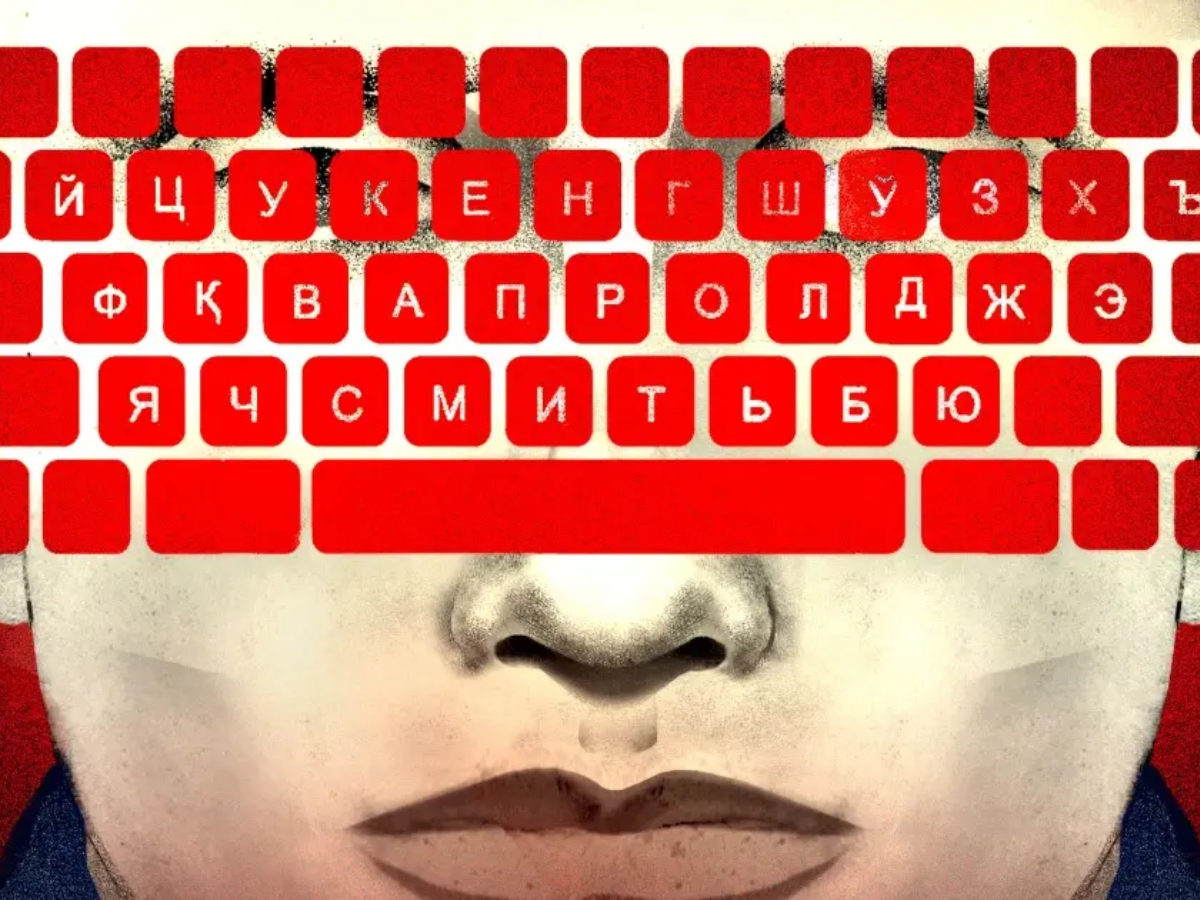

In China’s media landscape, censorship often works silently. Editors, guided by “stability” directives, routinely soften stories or erase key details before publication. (Image Credit: Human Rights Watch)

Every Chinese editor knows the drill. A story is ready to go—on a factory fire, a county protest or a hospital scandal and then a short “guidance” note lands in the newsroom chat--“Do not hype. Use only official releases. Promote stability.” Pages are reshuffled, verbs softened and the most revealing paragraph disappears. The public never sees the missing lines. In today’s China, the most powerful form of censorship is not the dramatic takedown, it is the quiet decision to publish less, later, or not at all. Reporters call it “self-discipline,” and it is a system, not a quirk—taught by propaganda authorities, reinforced by platform rules and policed by risk. As Reporters Without Borders has documented, the Party’s propaganda department issues daily instructions that media are expected to follow “to the letter,” or face sanctions.

This “self-discipline” is not vague etiquette. It rests on long-standing directives that rank topics by sensitivity and prescribe tone, placement and even vocabulary. Earlier guidance circulated by the Central Propaganda Department required strict control of disasters, accidents, and “extreme events,” reserving major incidents for central outlets and barring outside media from “extra-territorial reporting.” The logic is that the closer a story comes to collective grief or anger, the tighter the gate.

What readers experience downstream often looks like silence without visible force. That is by design. On social platforms, “ghost deletion” and invisible filtering mean a post may appear to publish but never truly circulates, or it vanishes after a brief window when few have seen it. Empirical studies of Weibo show that most deletions occur within minutes to hours, with roughly 90% gone within a day. Citizen Lab’s tests on WeChat have detailed real-time, automatic filtering of images and keywords, including for users outside mainland China. The effect is to discourage reporting at the source--why risk your press card for a story that platform rules will smother before it reaches an audience?

The same pattern governs headline writing and story framing. Editors learn to avoid “political incorrectness” not just in conclusions but in cues—adjectives that imply official culpability, verbs that suggest cover-ups, nouns that connect local mishaps to national policy. Freedom House has chronicled how news aggregators were instructed not to “hype” sensitive subjects and to use “super algorithms” that push Xi Jinping–era themes to the top of feeds. You can still write a piece, but if it contradicts the designed mood, it sinks.

Two beats make the logic especially visible--entertainment and disasters. In 2021 the broadcasting regulator and allied agencies moved to rein in celebrity culture—ordering platforms to curb “idol worship,” banning “effeminate men” from TV, and tightening control of talent shows. It was framed as cultural hygiene, but it also standardized what kinds of faces and stories could dominate screens. When a sector is told to be “healthy,” it learns to pre-emptively prune anything that might later be ruled unhealthy.

Disaster reporting shows how omission works when lives are at stake. During the deadly Henan floods of July 2021, foreign and Chinese outlets documented pressure on coverage and hostility toward independent reporting; watchdogs noted leaked directives warning media not to use “exaggeratedly sorrowful” tones or unauthorized figures. Separate official reviews later found that local authorities had “deliberately” hidden deaths. The net result for Chinese journalists is a chilling message: if tragedy cannot be told fully, it is safer to tell less—or nothing.

Investigative journalism has been squeezed most of all. Freedom House’s assessment is plain: state controls and economic pressure have “stifled high-quality reporting,” and probes are often permitted only after authorities open a case, stripping journalism of its watchdog role and rewriting it as a post-hoc explainer. Even when a newsroom gathers evidence, the calculus of risk—licenses, lawsuits, platform takedowns—pushes editors toward features, profiles, and harmless explainers, leaving hard accountability to wither.

A brief anecdote captures the atmosphere. After a bus crash, a city paper prepares a sober front-page story: driver overtime, faulty maintenance records, survivor accounts. As the press time nears, an instruction arrives: “Use Xinhua copy; avoid speculation; emphasize rescue and unity.” The editor swaps in agency text, moves the investigative graf to paragraph twelve, and trims the witness quotes. The headline becomes “Swift Response After Tragic Accident.” The most important facts still exist in a reporter’s notebook. They simply never make it to print.

China’s media scholars have a term for this system: “guidance of public opinion,” the doctrine that news must steer sentiment to protect Party authority. The China Media Project’s dictionary is blunt about the operational meaning: reject news “not in the interest of the Party,” prevent the spread of trends at odds with its aims, and ensure “unerring guidance” by respecting propaganda discipline. Under such rules, omission is not a failure of courage; it is the workflow.

Seen end-to-end, the pipeline is seamless. The propaganda apparatus prescribes tone and scope, platforms enforce invisible limits, editors internalise the red lines and reporters learn that “political incorrectness” can cost accreditation or freedom. What the public sees is calm—no spikes, no scandals, no messy debates—because the spikes have been sanded off upstream. The truth doesn’t have to be loudly denied if it can be quietly starved of oxygen.

This is why “self-censorship” understates the problem. It is not merely personal caution; it is a system that teaches omission as best practice and rewards those who master it. In today’s China, the loudest evidence of control is often the quietest: the blank space where a necessary sentence should have been, the vanished post no one noticed, the headline that avoids saying who failed and why.

(Aritra Banerjee is a defence and strategic affairs columnist)