From Gandhi's 1947 warning to today's alliances, Bihar still battles caste and communal ghosts.

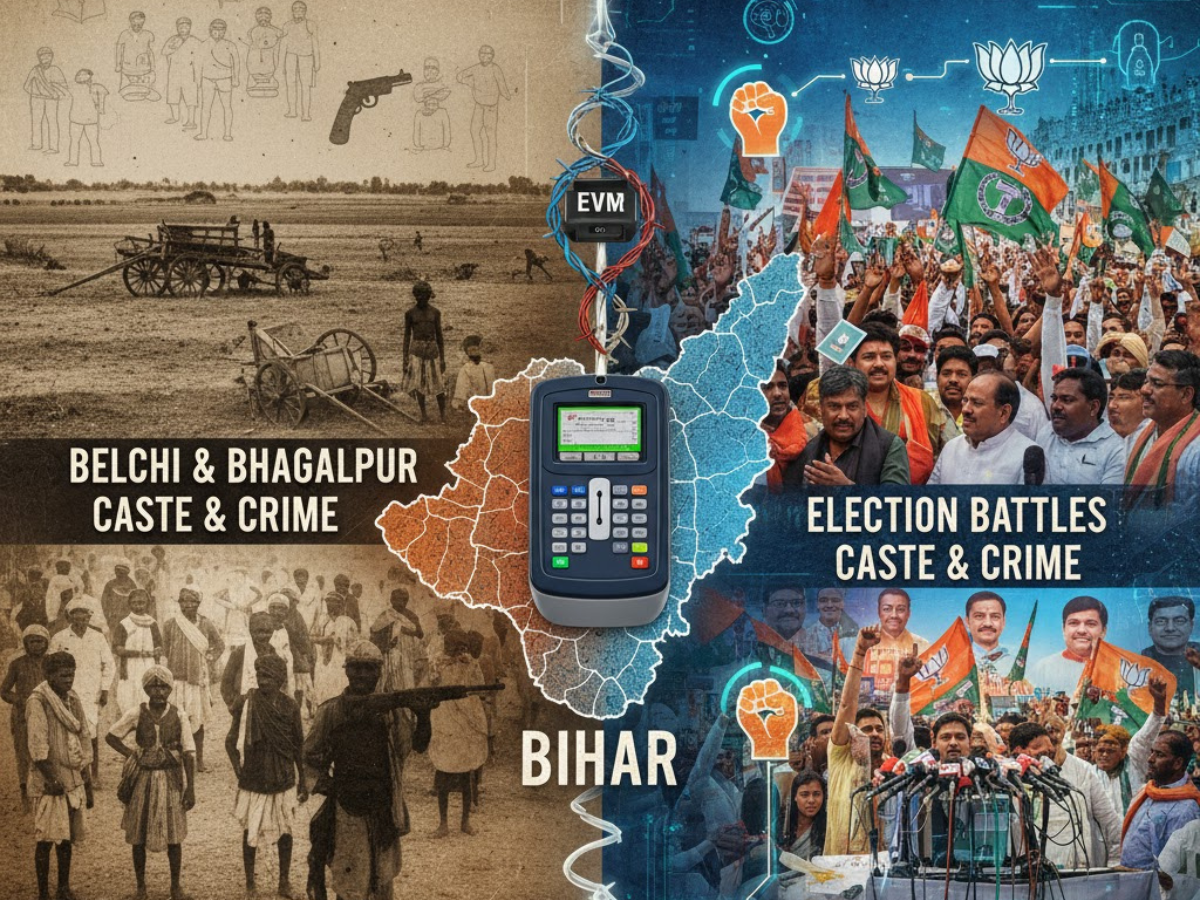

Historical and contemporary Bihar politics: From Belchi and Bhagalpur massacres to today’s election battles, caste and crime continue to shape the state (Photo: File)

NEW DELHI: "Congress has too many cheats today. There is a great wave of deceit. Those suspected of wrongdoing must either leave the Congress or be expelled. Some say there are many goons but we must tell them, we will not fear you, we will keep working. Good people must tell goons, you may kill us, but we won't run away".

These were not the words of any BJP leader, but of Mahatma Gandhi, spoken on March 18, 1947, at Bir village in Masaurhi, Bihar, after the communal riots. Seventy-five years later, Gandhi's words still echo in the political corridors of Bihar a state where caste, crime, and politics remain tightly entwined.

Today, as Bihar gears up for elections, the old question of "control over thugs and rioters" resurfaces once again. RJD leader Tejashwi Yadav, projecting himself as the chief ministerial candidate, and Congress leader Rahul Gandhi have accused Chief Minister Nitish Kumar's government of atrocities against Dalits and minorities. In response, the BJP, while not declaring its own CM face, has stood firmly behind Nitish, campaigning for votes across communities and minorities, while targeting the RJD-Congress alliance.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi, in a sharp counterattack this week, reminded voters that Bihar "will not forget the jungle raj for a hundred years". He termed the opposition bloc not a gathbandhan but a lathbandhan a coalition of criminals since "many of their leaders in Delhi and Bihar are out on bail".

Ironically, Rahul Gandhi's advisers appear to view the issue of Dalit atrocities as electorally advantageous, recalling how Indira Gandhi's 1977 visit to Belchi after a Dalit massacre turned into a political revival moment. However, they seem to forget that between 1970 and 1990, when Congress ruled Bihar, the state saw some of its worst communal riots and caste massacres, including the Bhagalpur riots and mass killings of Dalits in Jehanabad.

As a journalist since 1972, I have witnessed these events closely, interacting with Bihar's chief ministers from Kedar Pandey to Nitish Kumar. During the Bhagalpur riots and the Jehanabad massacres, Congress governments were in power, and as editor of Navbharat Times, our newsroom reported extensively on the horrors.

The Bhagalpur riots of October 1989 lasted for months, claiming over 1,000 lives and displacing thousands most of them Muslims. The riots began during a procession in Parvati and Lodipur areas, escalating into one of India's worst communal conflagrations. Houses were burnt, families were wiped out, and official figures undercounted the true toll. Human rights groups alleged political interference and administrative paralysis.

Judicial inquiries notably the Justice N.N. Singh and Justice Ram Nandan Prasad Commissions later found that the police acted with bias and local officials failed to respond decisively. The riots scarred Bihar's secular image and weakened Congress's standing. In the 1990 assembly elections, the Janata Dal rode the anger against Congress, leading to the rise of Lalu Prasad Yadav, marking a major turning point in the state's caste-driven politics.

The late 1970s were no less turbulent. In May 1977, the Belchi massacre in Nalanda district exposed the brutality of caste violence. Eleven Dalits and backward-class villagers were locked inside a hut and burnt alive by upper-caste Bhumihars amid a land dispute. Indira Gandhi's dramatic visit to Belchi travelling by train, jeep, tractor, and finally elephant through flooded terrain rekindled her political fortunes and symbolized her personal connection with the oppressed.

Through the 1980s, Bihar remained mired in caste conflicts. In Jehanabad and its adjoining regions, land disputes, caste militias, and Naxalite uprisings unleashed cycles of revenge and mass killings. In June-July 1988, a brutal attack near Nomhigarh and Nagwan wiped out several Dalit families. Reports said 19 Harijans were killed. Fingers pointed at local power brokers and political patrons.

These massacres were not random acts of caste hatred; they reflected a deep nexus of politics, power, and land. In many cases, politicians and local strongmen either protected the perpetrators or benefited from the chaos. Several inquiries dragged on for years, ending without justice. Shockingly, even leaders accused of shielding caste killers were rewarded with tickets and positions.

During one informal conversation, President Shankar Dayal Sharma reportedly expressed his anguish to me over the Congress party's protection of such criminal politicians. That anguish summed up the moral crisis of Bihar's politics where caste equations, muscle power, and money often outweighed justice and humanity.

From Gandhi's moral warning in 1947 to today's election slogans, Bihar's political landscape continues to wrestle with the same haunting question: how to control the thugs and rioters who thrive under political patronage. The answer, it seems, still eludes the state and the nation.