The Official Chinese Historiography presents Tibet joining the mainland in 1951 through a smooth and friendly process. Such a narrative, which has been consistently repeated in textbooks, museums, and diplomatic statements, is based on the claim of long-standing sovereignty of the Chinese dynasties over Tibet. However, a thorough examination of the historical documents, diplomatic exchanges, and local governance not only clarifies the facts but also brings to light aspects that are inconvenient for the official narrative. The story of Tibet’s integration is not the story of the continuation of the Chinese divine right imperial rule but of a twentieth-century occupation which was later justified through the selective use of history and political intimidation.

Imperial Continuity Myth

Beijing’s central claim hinges on conflating the reach of the Mongol Yuan and Manchu Qing empires with modern Chinese statehood. This is a category error. The Yuan and Qing were multiethnic imperial formations that governed through flexible arrangements of suzerainty rather than uniform territorial administration. Tibet under the Yuan was overseen through patron priest relations, not provincial governance, and no Chinese civil administration existed on the plateau. Under the Qing, imperial ambans were stationed in Lhasa, yet Tibet retained its own legal system, taxation, army, and foreign religious networks. Even Qing court documents distinguished Tibet as an outer dependency, not an integrated province comparable to Sichuan or Shaanxi.

By collapsing imperial suzerainty into national sovereignty, the Chinese Communist Party projects a modern nation-state logic backward onto premodern empires. International historians of Inner Asia have long observed that empires governed diversity rather than eliminating it. To claim that Qing oversight equates to Chinese rule is to misunderstand both empire and China itself. It is also to ignore the collapse of Qing authority in 1911, after which Tibet functioned for nearly four decades with its own government, borders, currency, and diplomatic interactions.

Academic Repression

This historical complexity is systematically erased within China’s research ecosystem. Since the 1990s, Tibetan studies have been folded into party-supervised institutions tasked with producing politically correct scholarship. Archival access is restricted, foreign collaboration is tightly monitored and dissenting interpretations are treated as threats to national unity. Chinese scholars who acknowledge Tibet’s de facto independence between 1912 and 1950 face professional marginalisation, while official publications recycle predetermined conclusions.

The result is not scholarship but narrative engineering. Party aligned research centres export glossy monographs and exhibitions that mimic academic form while rejecting academic method. Outside China, these claims struggle under peer review, yet they circulate widely in diplomatic briefings and media outreach. This asymmetry matters. When state power dictates historical truth, the past becomes an instrument of governance rather than a field of inquiry.

Symbols Without Substance

Much of Beijing’s evidentiary case rests on symbolic artefacts. Seals allegedly granted by emperors, tribute missions to imperial courts, and ceremonial titles are presented as proof of sovereignty. This is a profound misreading of premodern diplomacy. Across Asia, tributary exchange functioned as a mechanism of regulated interstate contact, not submission. Kingdoms from Korea to Ryukyu participated in tribute while retaining full internal autonomy and independent foreign relations.

Tibetan envoys travelled to imperial courts as part of this wider diplomatic ecology–often on religious rather than political terms. Tribute was reciprocal. It involved imperial gifts and recognition, not unilateral control. To treat these exchanges as evidence of ownership is akin to claiming that medieval European kingdoms belonged to the papacy because they sought blessings. Symbols conveyed hierarchy, not annexation.

From Agreement to Annexation

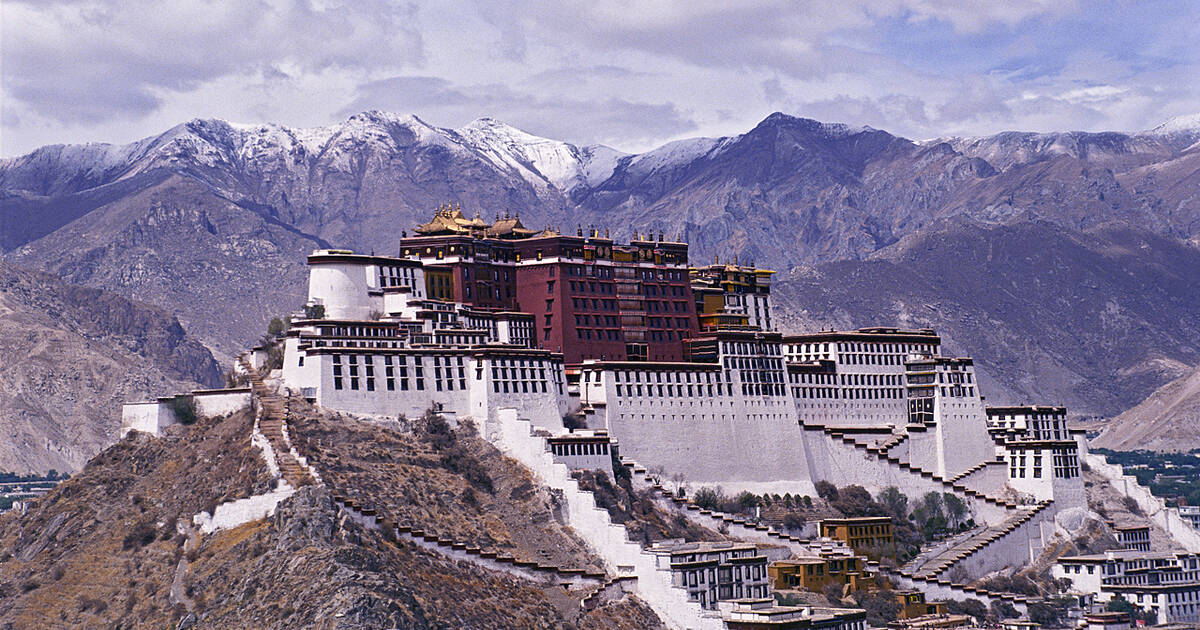

When the People’s Liberation Army entered eastern Tibet in 1950, it did so by force, defeating Tibetan units at Chamdo. The subsequent 1951 agreement was signed under military duress. Tibetan representatives lacked the authority to negotiate sovereignty. Even the document itself promised autonomy, respect for religion and non-interference, commitments soon violated through land reform, political purges and demographic engineering. The peaceful union was peaceful only in propaganda.

The myth of ancient sovereignty serves a present purpose. Beijing, by reframing conquest as reunification, seeks moral legitimacy and legal insulation against international scrutiny. Yet history resists such compression. Tibet was not a lost province returning home but a distinct polity absorbed through power at a moment of imperial transition. Recognising this does not resolve today’s political disputes, but it clarifies them. A durable future for Tibet cannot be built on invented lineage and silenced archives. It requires confronting the past as it was, not as power demands it to be. For policymakers and readers alike, disentangling myth from record is not an academic exercise alone. It shapes international law, minority rights, and the credibility of historical claims used elsewhere. Accepting manufactured continuity today sets a precedent that can justify coercion tomorrow, weakening the norms that protect weaker societies from revisionist pressure worldwide.