As the Durand Line crumbles, Pakistan faces a crisis even more severe than what it faced during Op Sindoor. (Image: CeGIT)

Pune: Ever since General Asim Munir (now self-appointed Field Marshal) took over as Army Chief, Pakistan has been engaged in conflict after conflict. A massive public outrage against the Army following the arrest of Imran Khan in May 2023; an exchange of missiles with Iran in January 2024; a crippling four-day conflict with India in May 2025; religious and sectarian violence, and now the open conflict with Afghanistan along the Durand Line, which threatens to extend into a long, bleeding war. Add to this the intensification of the freedom struggle in Balochistan and upheaval in Pakistan Occupied Kashmir. In all this, the Pakistani Army can legitimately claim to have attained victory in only one of its many conflicts—its war against its own people.

The eruption along the Durand Line was something that had to be coming. Waziristan—the rugged mountainous region adjoining Afghanistan in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province—had been on the boil for the past three years with the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), ostensibly supported by the Taliban regime in Afghanistan, gaining virtual control of the tribal area. Pakistan’s decision to deport Afghan refugees staying on its soil for almost a decade had rankled.

Pakistan claimed that TTP cadres crossed the Line to launch attacks and then fled back for sanctuary on the other side. The Taliban claimed that Pakistan harboured members of the ISIS—their bitter rival—on their soil. They also harboured resentment at the policy to relocate the Jaish-e-Mohammed and Lashkar-e Taiba to Khyber Pakhtunkhwa after Indian strikes at their bases in Punjab. All this has been merely in keeping with the Pakistani policy of “good terrorists” and “bad terrorists”. The tensions along the Afghan and Pakistani border had been rising, with increasing exchanges of fire from both sides, and the closure of border crossings. And now the pot was about to boil over.

DISINTEGRATION OF THE DURAND LINE

The trigger for this bout came with a series of attacks on Pakistan security forces in early October, one which killed 11 Pakistani soldiers, including a Lieutenant Colonel and a Major. It was followed almost immediately by a strike on a police training camp at Dera Ismail Khan that claimed seven policemen. This triggered off an Pakistani air attack—ostensibly by F-16 fighters, in Kabul and Paktika Provinces which reportedly targeted the headquarters of the TTP chief Noor Wali Mehsud. The attack killed civilians on the ground, but attained nothing else. Even Mehsud emerged a few days later, unscathed and promising revenge. But that violation led to a violent reaction. The Durand Line virtually erupted all along Khyber Pakhtunkhwa with Pakistani and Afghan troops exchanging small arms and artillery fire, capturing posts on either side, and even rushing tanks to the border.

The Taliban claimed to have killed 59 Pakistani soldiers (Pakistan put the toll at 23, and claimed to have killed 200 Taliban fighters) and captured posts in Spin Boldak, even displaying trousers and rifles of Pakistani soldiers whom they claimed had surrendered. Memes of “93,000 soldiers—Pakistan-1971; Afghanistan-2025” flooded social media, along with photos of captured Pakistani personal and equipment. Perhaps the comparison to the 1971 war may not be so far-fetched after all. Pakistan is indeed facing its greatest existential threat since 1971, and like in 1971, it is a crisis created entirely by its own doing.

To add fuel to the fire, the recent eruption took place at a time when the Afghan foreign minister Amir Khan Muttaqi was in New Delhi for a major reset in Indo-Afghan ties, in which India agreed to reopen its embassy in Kabul and intensify its humanitarian aid. Predictably, it led to accusations within Pakistan that this was, “a proxy war, waged by India.” But, what it merely highlights is the complete failure of Pakistan’s policy of acquiring “strategic depth” through Afghanistan by helping the Taliban come into power in Kabul, both in the late 1990s, and again in 2021. But their hopes of a pliant regime proved to be anything but that. The Taliban proved to be exceptionally independent, refusing to accept external influence and chartering their own course. Their success also gave the impetus for the TTP to intensify its own actions in Waziristan and gradually gain control of the border areas. As their influence expands, perhaps it is Pakistan that could be adding strategic depth to Afghanistan.

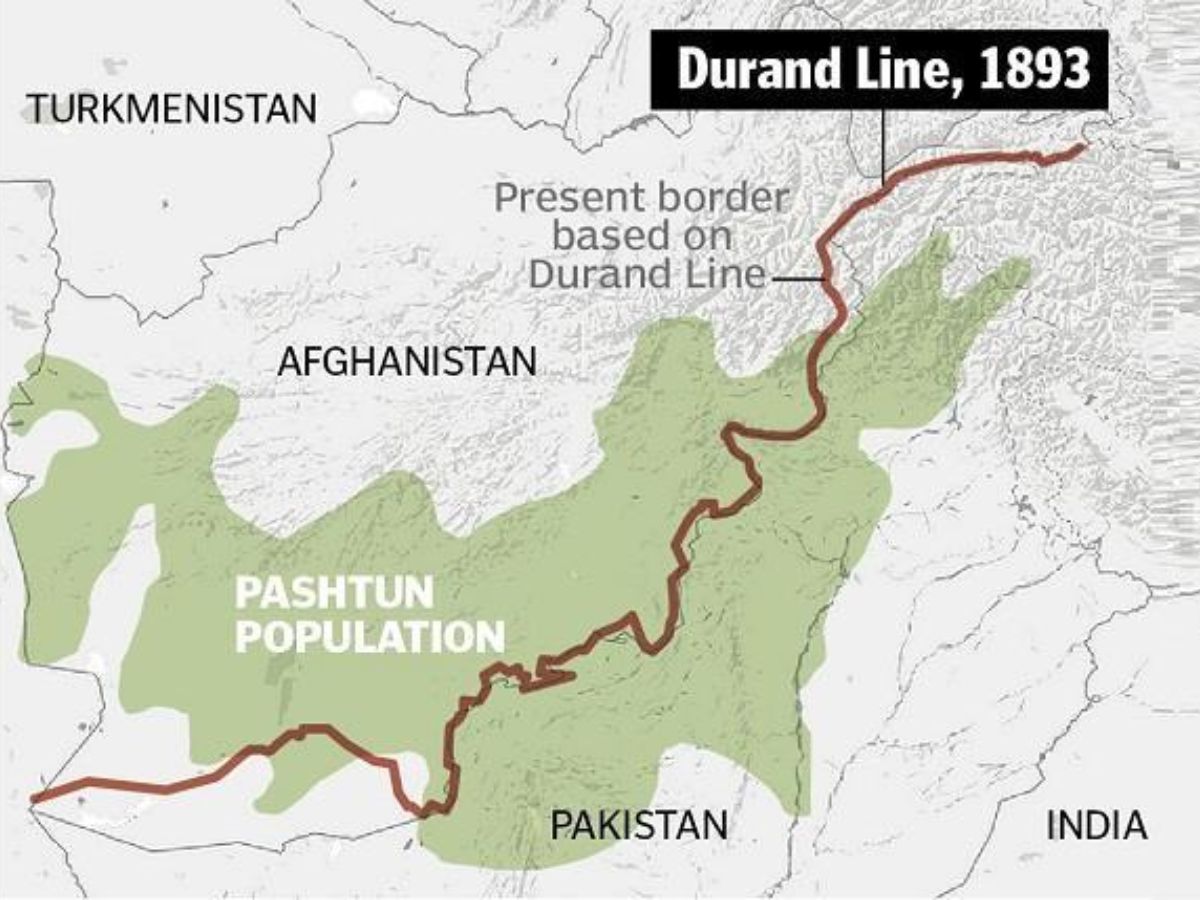

Pakistan has also failed to evaluate its own tortuous history with Afghanistan and the centrality of the Durand Line. The 2,640 kilometres long line separating Afghanistan from Pakistan was drawn by Sir Mortimer Durand in 1893, more to separate the area of influence between British India and Afghanistan, rather than a permanent boundary. It did not take it to consideration the fact that millions of Afghan Pashtuns live east of the line. When Pakistan was created in 1947, Afghanistan opposed its creation and claimed all Pashtun lands in its area, right up to the Indus River—which they claimed was the natural boundary. Hostilities broke out as far back in 1961 and again in the 70s, when successive governments claimed the area of “Pashtunistan”. No Afghan government has ever recognised the Durand Line and perhaps Pakistan hoped that a pliant, grateful Taliban regime would finally do so.

But the Taliban proved even more intractable, not even calling the Durand Line by its name, but referring to it as “The Hypothetical Line.” Merging the Pashtun dominated areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa into Afghanistan is an oft-stated aim and the actions of the TTP are but an extension of it.

India’s policy of patience and providing sustained humanitarian aid to a war-wracked Afghanistan has paid off. Its engagement with the Taliban regime also reflects sensible realpolitik. There is great goodwill towards India for its actions, as opposed to the resentment directed towards Pakistan for its constant interference in Afghan affairs. India needs Afghanistan for connectivity towards Central Asia and the landlocked Afghanistan needs Indian trade—something denied by the hostile Pakistan sandwiched in between. Yet fortunately, in spite of the physical distance, India has managed to bridge the gap quite adroitly. Perhaps, if Chahbahar port gets activated, the connectivity will be further enhanced.

PAKISTAN’S MOMENT OF TRUTH

It has been a rather rude awakening for Pakistan. Its policy of “strategic depth” has given way to fears of “a two-front war”. Its claims of forming an “Islamic NATO” after the signing of a defence pact with Saudi Arabia, has been revealed as hollow. Even its abject subservience to USA has rebounded. For all of Shehbaz Sharif’s blatant flattery of Trump at the Gaza Summit in Egypt, his government had to backtrack on its support to the Gaza Peace Plan, stating that it did not reflect the Palestinian cause adequately. Supporters of the radical religious group, Tehreek-e-Labbaik, began a long march from Lahore to Islamabad to protest at the US embassy and had to be stopped by police firing and force. In all this, the freedom movement in Balochistan is gathering momentum—the Jaffar Express was derailed again last week. There are violent protests in Pakistan Occupied Kashmir, the economy is still based on dole-outs, and Imran Khan continues his harangue against the military rulers, even from jail. It has all the makings of a perfect storm.

As the Durand Line crumbles, Pakistan faces a crisis even more severe than what it faced during Op Sindoor. That was a message by India to show what damage could be inflicted if it did not stop its support for terrorism. Op Tandoor—as some sections of Pakistani media have named it—is more that. The two countries may not enter into a sustained war, but the slow bleed that the TTP can inflict could take an unsustainable toll. The 48-hour ceasefire brokered by Qatar and Saudi Arabia has broken down and at the time of going to print, Pakistan launched fresh airstrikes inside Afghanistan, which killed 3 cricketers, and other civilians on ground, and the TTP too have intensified their actions. A suicide attack by the TTP on a Pakistani post killed seven soldiers—more will undoubtedly follow. It would require the deployment of a major portion of the Pakistani in the rugged terrain there, just to have some measure of control—and tensions with India could tie down its troops even further. They could just lose control and any kind of government influence in the border areas. This will add impetus to the freedom struggle in Balochistan, creating another front for the Pakistani army. And in all this, radical Islam—as propagated by the TTP—could take root and create a religious divide that spreads across all of Pakistan. This holds long-term dangers—even for India, which could also be affected by spreading religious fundamentalism. The world—especially the United States and China would not let a nuclear-armed state go under, and will continue to keep Pakistan afloat. But for how long? Its moment of truth is fast approaching, and the sooner they realise it, the better.

Ajay Singh is an award-winning author of eight books and over 250 articles. He is a regular contributor to The Sunday Guardian.