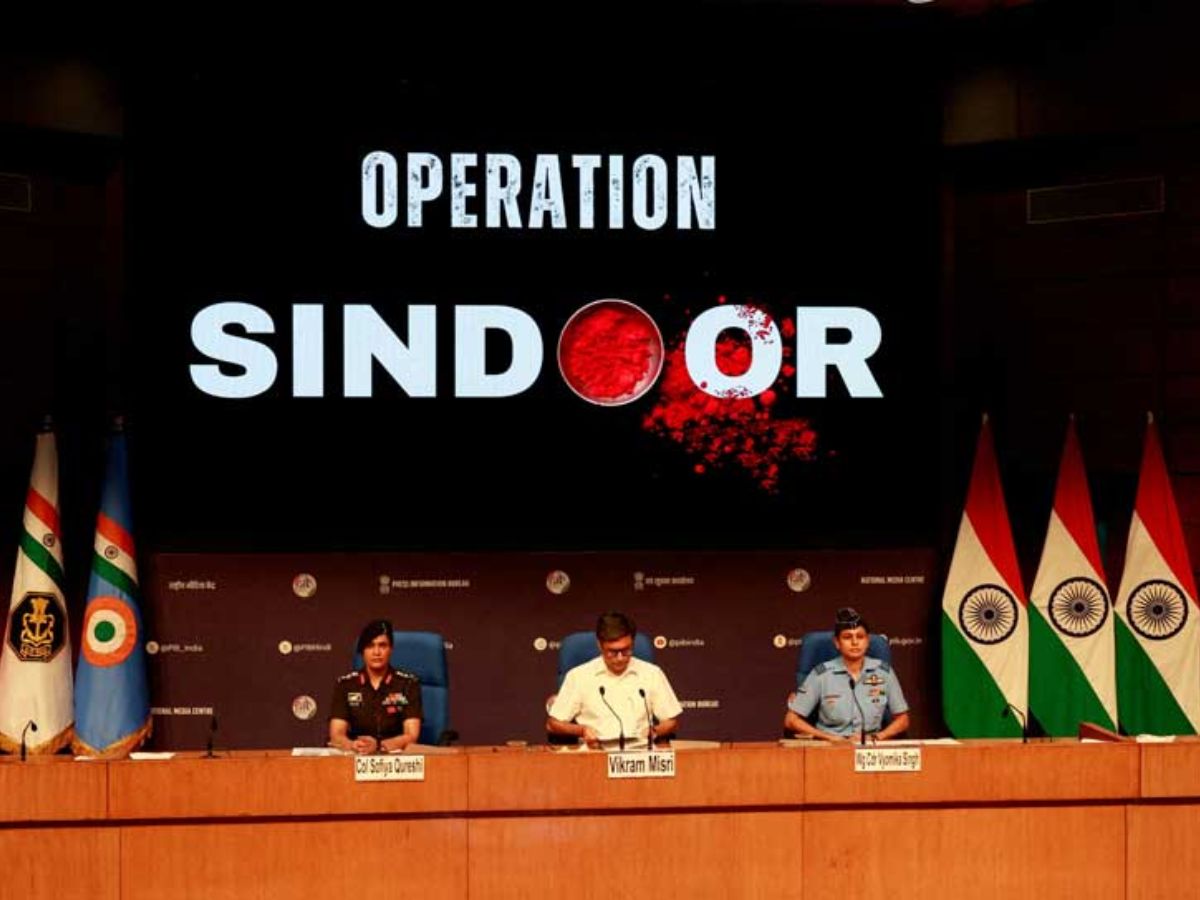

New Delhi: A section within India’s security establishment is pressing for urgent reforms in strategic communication after Operation Sindoor exposed weaknesses that allowed Pakistan to gain the upper hand in the contest of narratives. While the military operation was executed with precision and achieved its strategic objectives, the information war that followed told a very different story. Pakistan’s account dominated international coverage, while India was left playing catch-up.

This gap has been particularly troubling because India already maintains at least two dedicated verticals inside the defence system whose sole mandate is strategic communication. In practice, these structures did not deliver when tested, officials told The Sunday Guardian. Similarly, the National Security Council, which could have coordinated messaging across services and ministries, was not involved in the exercise. Whatever impact was achieved came through the top political leadership using its own informal setup. Without a defined authority, there was no accountability. Since no single official or institution was responsible, no one bore the burden of results. Officials say this vacuum was one reason fake and imaginary news spread unchecked, causing irreparable damage to the credibility of Indian electronic media at the global level.

Pakistan, by contrast, worked from a single playbook. Its Directorate General of Inter-Services Public Relations (DGISPR) functioned as the authoritative voice, issuing timely on-record briefings to both domestic and foreign media. The DGISPR line was reinforced by Pakistan’s defence and foreign ministers, who repeatedly engaged with international journalists. Claims that the Pahalgam attack was a “false flag,” that India had suffered heavy losses, and that Rafale fighter jets had been downed, quickly gained traction abroad. Global headlines reflected those points, often overshadowing India’s assertion that multiple terror headquarters and Pakistani military installations had been struck.

India’s approach looked hesitant and fragmented. Press conferences in Delhi were organised only after claims and counter-claims had already taken hold, and even then, they were guarded affairs with a narrow pool of invitees. This restrictive format fed the perception that India was unwilling or unable to speak openly, while Pakistan’s frequent briefings appeared more confident. International correspondents later complained they received little or no structured briefing from Indian authorities, and some were criticised for “not showing India’s side of the story.” As one foreign reporter remarked, “You cannot expect us to reflect your position if you don’t even tell us what it is.”

The credibility deficit was compounded by India’s own television media, which enjoys limited trust abroad. Loud monologues by a few TV anchors did not substitute for authoritative official statements, and in their absence Pakistan’s version of events filled the vacuum. Much of the information flow within India itself was informal. For example, much of the news emerged through WhatsApp groups run by a few journalists and informally supported by defence officials. Updates circulated there, leaving those inside the groups better informed while most foreign correspondents were left with no official channel at all.

Those who were a part of the groups had something to fall back on for information, mostly had to rely on their own personal contacts to file stories. At the same time, officers shared details with journalists based on personal preference, producing contradictions instead of clarity. The result was not a unified message but a patchwork of fragments.

Compounding the problem was a misplaced belief within sections of the establishment that India’s claims would be taken at face value internationally, an official told The Sunday Guardian. Officials assumed that simply stating or repeating a position would be enough to convince foreign governments and media. But no evidence or dossiers were presented to substantiate India’s case, while Pakistan had its counter-narrative backed by material ready to circulate. The imbalance was obvious: one side arrived with prepared exhibits, the other relied on assertion.

Against this backdrop, the decision to formally recognise officials and reward them for their “excellent work” in handling communication during Sindoor has raised questions. Insiders point out that the commendations reflected individual effort under pressure, not systemic success. For many, the recognition despite failure highlights a deeper flaw: a system where accountability is diffused and outcomes matter less than appearances. As one official admitted, “We won the operation, but we lost the telling of it and yet no one was held accountable.”

“Was there any single authority where journalists could reach out to check on the authenticity of information in a fast-moving development? The answer to this will reveal what is broken that needs to be mended,” another official commented.

The concern now is not only retrospective but prospective. Voices within the establishment warn that unless reforms are introduced, India is bound to repeat these mistakes in future crises. Proposals now being discussed centre on creating a unified messaging mechanism, empowered to brief in real time, rebut rumours before they harden, and address both domestic and international audiences with credibility. Crucially, advocates argue, such a body should not be staffed only on the basis of military rank or years of service, but should also draw on communication professionals, analysts and outside experts.

“When the next war-like situation arises, a dedicated body must be there—one that can be held accountable and recognised on the basis of results,” an official involved in the review said.

Operation Sindoor demonstrated India’s operational capability, but also revealed the fragility of its narrative preparedness. Without accountability, evidence-based messaging and professional expertise, adversaries will continue to shape the story of who prevailed—and India will continue to risk strategic victories being overshadowed by someone else’s telling.