New Delhi: Many theories are swirling between Kathmandu and New Delhi about what caused the sudden, violent overthrow of the Nepalese government, including severe damage to its historic parliament, the Singha Durbar built in 1908.

Was it another incident of a “youth revolution”? Were there deeper factors at play? Who gains from this? And who loses? Were there external parties involved?

These questions have been asked again and again in recent years in the Indian subcontinent, from Sri Lanka in 2022 to Bangladesh in 2024, and perpetually about Pakistan’s regular crises. In some minds, the question also arises why this does not happen in India?

This essay aims to address some of these questions with the overarching argument that, in fact, what is happening in the Indian subcontinent, sometimes referred to as “South Asia”—which is a bit of misnomer because the Indian subcontinent differs in many significant ways from the rest of Asia—is that the frame that was constructed at the end of British rule in the late 1940s is now coming apart.

The “South Asia”, a term popularised by American academics in the 1950s to reflect their own Cold War perspectives with its neat divisions upon which global politics could be played with ease and intrusion, is coming to an end.

A combination of demographic restlessness, civic dissatisfaction, and social media sunlight upon everyday intrigue, a characteristic of the region, has vigorously disturbed the status quo.

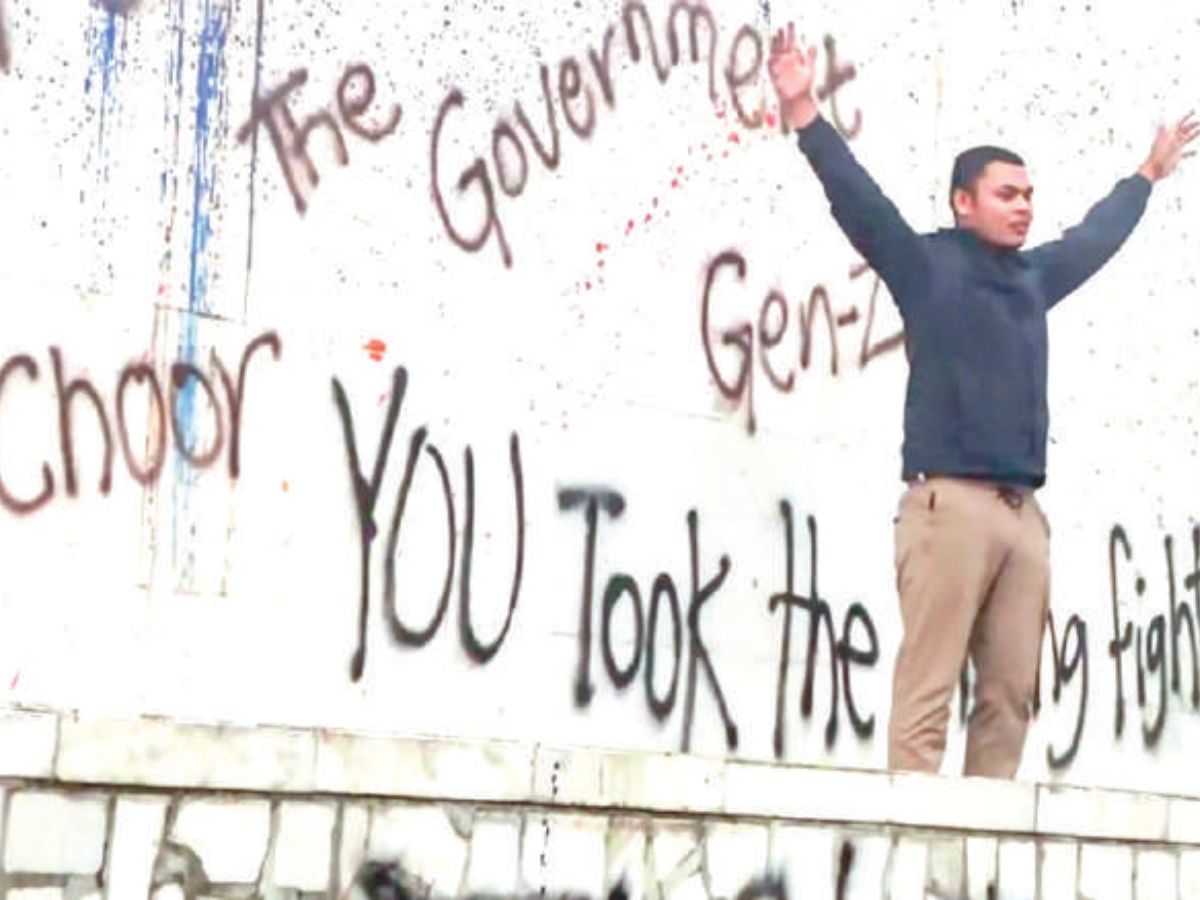

The violent overthrow of Sheikh Hasina’s government in Bangladesh during the “July Revolution” of 2024, the dramatic toppling of the Rajapaksa dynasty in Sri Lanka’s 2022 “Aragalaya,” and the explosive “Gen Z protests” that brought down Nepal’s government in September 2025 are not isolated national crises. They are interconnected seismic shocks along a regional fault line—a line created by the very framework of the post-colonial state system in South Asia.

The current turmoil is the violent, chaotic unwinding of a political tapestry woven not by the subcontinent’s people, but by the British Empire. This colonial framework, designed for extraction and control, is proving fundamentally unsustainable.

The very nature of these nation-states, from their administrative structures to their ethnic divisions and economic vulnerabilities, was a by-product of British colonial policy. Now, after decades of festering internal pressures, the threads of this legacy are snapping, and in their place, a new, uncertain, but potentially more authentic South Asia is emerging.

The British did not merely conquer South Asia; they re-engineered it into a machine for imperial benefit. Through colonial cartography, they drew arbitrary lines on maps that became national borders, severing ancient commercial and cultural links while forcing disparate communities into new, artificial administrative units.

They imposed centralized states, a European concept alien to a region of historically fluid kingdoms. The colonial state’s purpose was explicit: the systematic extraction of wealth. Its institutions—the civil service, the police, the army—were not instruments of public service but of subjugation. This inheritance of a powerful, centralised, and inherently authoritarian state apparatus has been the tragic birthright of post-colonial South Asia.

The “steel frame” of the civil service, for example, was designed to be aloof from the population it governed, perpetuating a chasm between the rulers and the ruled. Police forces were modelled on the Royal Irish Constabulary, a paramilitary force designed to suppress insurrection, not uphold community law.

The economies were rewired; Bengal, once a global textile manufacturing hub, was systematically de-industrialized to consume British-made cloth, its weavers driven into poverty. In Ceylon, the British institutionalized ethnic division through the Colebrooke-Cameron Reforms of 1833, which unified the island but also introduced communal representation in the Legislative Council, appointing members based on race and favouring the Tamil minority for administrative roles, thereby planting the seeds of future conflict.

Even Nepal, which was never formally colonized, was hemmed in by the 1816 Treaty of Sugauli, its borders fixed to suit British India’s strategic anxieties.

The 2024 revolution in Bangladesh is a textbook case of this legacy imploding. The immediate trigger—a High Court verdict reinstating a 30% quota for the descendants of 1971 war veterans in government jobs—was the spark in a powder keg of grievances against a state perceived as corrupt and nepotistic. The student-led protests were met with brutal force by the very institutions of the colonial state: a police force that opened fire on demonstrators, leading to over a thousand deaths, and a ruling party that unleashed its student wing as enforcers.

The violence that ensued was not just a rejection of Sheikh Hasina’s 15-year rule, but a wholesale repudiation of a political system where the state apparatus serves an entrenched elite, a direct continuation of the colonial model. The fury on the streets of Dhaka, fuelled by vast economic inequality despite impressive GDP growth, exposed the failure of a post-colonial state built on an extractive economic foundation.

Similarly, Sri Lanka’s 2022 “Aragalaya” (The Struggle) was a mass uprising born from a complete collapse of the post-colonial social contract. The country’s first-ever sovereign debt default was the culmination of decades of mismanagement, culminating in the Rajapaksa family’s catastrophic policies: reckless tax cuts, a disastrous overnight ban on chemical fertilizers that decimated agriculture, and rampant corruption.

But beneath the immediate economic triggers lay the deeper fractures of the colonial past. The protest movement was remarkable for its multi-ethnic character, temporarily uniting Sinhalese and Tamils who had been pitted against each other for decades by the legacy of British “divide and rule” policies. The storming of the presidential palace was a powerful visual metaphor: the people reclaiming a seat of power that had, since independence, remained disconnected from their realities, operating within a centralized state structure that had proven incapable of resolving the island’s deep-seated ethnic and economic problems.

The 2025 implosion in Nepal, long predicted by observers, followed a similar script. What began as the “Gen Z protests” against a government ban on 26 major social media platforms quickly morphed into a nationwide revolt against the entire political class. The ban was the final insult to a generation steeped in digital connectivity, but their rage was fuelled by tangible grievances: youth unemployment running at 20%, forcing over 2,000 young Nepalis to leave the country every day for work, and the flagrant displays of wealth by the children of politicians—the “Nepo Kids”—on the very platforms the government sought to silence.

The ensuing violence, which saw protestors killed and parliament set ablaze, signified a complete breakdown of trust in a democratic system that had failed to deliver anything but instability and elite enrichment since the monarchy’s abolition.

In an earlier time, strategic interests of Western powers in the Himalayan region, and rapid advance of Chinese investments, intrigue and infrastructure to diminish India’s role in the country, would keep things in a Great Game-esque limbo for an almost infinite amount of time. Clearly, no more.

Across the subcontinent, we are witnessing the systemic failure of the post-colonial state. Its institutions are not merely creaking; they are breaking. Its economies, still caught in dependencies established in the colonial era, are failing to provide for their young, growing populations. The social contract is void. The violence is a symptom of this profound decay—the desperate anger of people denied opportunity, excluded from power, and stripped of hope in the very state that claims to represent them.

But that’s not the only truth. Some have asked, even malevolently, why this kind of “revolution” does not occur in India. There is simple data available to explain that. Such “revolts”, even if wholly organic, which is almost never true, are fuelled less by the extremely poor than by the disaffected aspirational classes.

In India, there has been a consistent betterment of the lives of such classes—for instance, in the last decade as the rank of the Indian economy has risen from 10th to 4th spot, there has been four rounds of tax breaks from a limit of two lakhs rupees to the current 12 lakh rupees. A monthly salary of one lakh rupees was impossibly aspirational for most Indians even a generation ago. That this is now considered too low to even tax is a vital demonstration of what keeps aspirational Indians hopeful.

This is critical because none of the other countries that have gone up in flames in the region, including the nearly perpetually in crisis Pakistan, have any semblance of a real middle class.

During approximately the same period, more than 270 million Indians have escaped extreme poverty and rate has fallen, as estimated by World Bank, from 27.1 per cent to 2.3 per cent. Nepal, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka were going through prolonged and acute economic problems when the violence occurred—on the contrary, in the last quarter the Indian economy defied expectations to grow 7.8 per cent.

This is why India’s Gini Coefficient improved from 28.8 to 25.5 between 2011-23. It is now—according to World Bank estimates—the fourth most equal society in the world. Many Indian social analysts often base arguments on familial memory or anecdotal evidence and are often data-ignorant, therefore their understanding of India is based on how they think about the country in their head rather than an accurate reflection of a very rapidly changing nation of around 1.5 billion people.

There is also a deeper subliminal reason for the relative peace in India that analysts often miss—there is a cultural resurgence, triggered in part by economic prosperity, and in part by a sort of back-to-the-roots identity socio-cultural transition towards a non-Western language of modernity that is now underway in the country. This works to expand both the boundaries of inclusion and aspiration.

Yet, this violent unravelling is not just an end; it is also a convulsive beginning. Out of the chaos, a new South Asia is struggling to be born. The popular uprisings have shattered the aura of invincibility surrounding entrenched political dynasties. They are driven by a digitally-native youth who organize on encrypted apps, bypass state media, and articulate demands for systemic change, not just new leaders.

They are demanding inclusive and accountable governance, rejecting the crony capitalism that has defined their parents’ generation. The unravelling of the British-made tapestry is a painful, bloody, and uncertain process. But it is also a necessary one. The old order, a relic of an imperial past, is dying. The future of South Asia will not be determined by the ghosts of the Raj, but by the aspirations of its people, who are now, for the first time, weaving a tapestry of their own.

Hindol Sengupta is professor of international relations at the Jindal School of International Affairs, and director of the Jindal India Institute, at the O.P. Jindal Global University.