US move to ban BLA seen as linked to rare earth scramble in Balochistan; report highlights mineral wealth, geopolitics and local resistance.

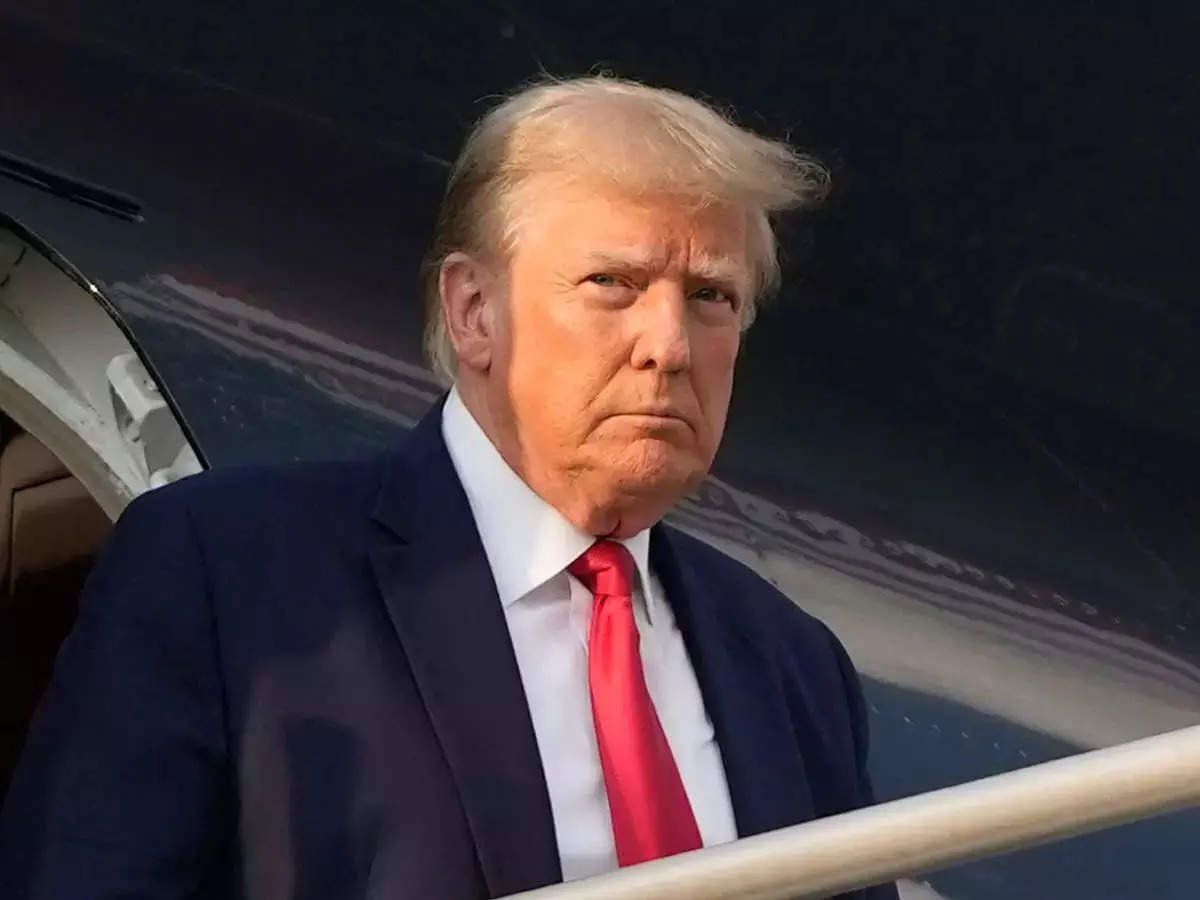

Former US President Donald Trump’s move to ban BLA seen as a strategic step to secure rare earth minerals in Balochistan amid US–China rivalry

New Delhi: The latest pro-Pakistan steps taken by Washington, including the designation of the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA) as a terrorist organization earlier this month, are likely linked to the scramble for rare earth minerals buried beneath the deserts and mountains of Balochistan, as per a recently released report by local groups.

By designating the BLA as a terrorist organization, freezing its assets and criminalizing its support networks, something which Pakistan had been pushing for long, the United States has effectively cleared the ground for American companies to invest in one of the world’s richest but most unstable mineral frontiers.

A 74 page report, "Rare Earth Minerals and Copper Reserves in Balochistan (Report No. ER01/2025)", compiled by independent local investigators identified as “Giajaim” team, has detailed how the province’s mineral wealth is now at the center of global competition between the United States and China, with the Baloch themselves rejecting all extraction without their consent.

The group, whose name in the Balochi language refers to the search for hidden truths, has said that isan autonomous institution that collects and analyzes security and economic data on Balochistan.

Its purpose, according to the authors, is to provide accurate information so readers can understand both national and regional developments in a wider perspective.

The report draws on multiple credible sources and is not an academic exercise.

The document opens with a stark statement that while Balochistan holds vast reserves of copper, gold and rare earth elements, the Baloch nation is consistently excluded from decision-making and categorically rejects externally imposed projects.

It goes on to explain why these resources matter. Rare earths, a group of seventeen elements including neodymium, dysprosium and yttrium, are described as the “oil of the twenty-first century,” indispensable for smartphones, electric vehicles, renewable energy, missile systems and advanced medical technology. Copper, too, is portrayed as strategic: each wind turbine needs up to seven tons, while solar and electric grids depend heavily on copper wiring.

Balochistan’s own geology is mapped in detail in the publication.

The ophiolite belts of Muslim Bagh and Khuzdar may host heavy rare earths, coastal sands could contain monazite, and early surveys in Chagai suggest both granite and metamorphic rocks may carry valuable deposits. Together with copper reserves estimated at 6.5 billion tons including the massive Reko Diq and Saindak deposits the province’s subsoil places it among the richest mineral regions in the world. Yet, as the report underlines, most of these resources remain underdeveloped or exported at prices far below the global average, with negligible benefit to local people.

While China has long held the advantage in this field, Washington is now moving in swiftly. Beijing has invested heavily in Balochistan through the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor and the Saindak copper-gold mine.

But insurgent attacks have slowed progress and created openings for rivals.

The report tracks how the United States has stepped in over the past two years: President Donald Trump elevated minerals to a priority sector in 2024; American officials attended Pakistan’s Minerals Investment Forum in 2025; and new trade agreements signed this summer reduced tariffs and gave U.S. firms access to Balochistan’s oil and mineral projects.

The August 2025 decision by Trump administration to outlaw the BLA, as per the report, is more about creating stability for investment rather than counterterrorism, thereby clearing the ground for American companies to operate in the region.

The narrative places these moves in the context of wider geopolitical maneuvering. Washington is seeking to diversify supply chains away from China, secure critical inputs for its defense and technology sectors, and offer Islamabad an economic lifeline at a moment of debt and political instability.

For Pakistan’s leadership, minerals are presented as a solution to chronic economic woes. Army chief Asim Munir in August called Balochistan’s rare earth “treasures” a path to debt relief, while Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif has promised that no raw materials will be exported, insisting foreign companies process minerals locally.

Yet behind the fanfare, the report stresses the persistence of old grievances. Balochistan contributes less than 5 percent of Pakistan’s GDP despite supplying 40 percent of its gas; royalties from Sui have long bypassed the province; and communities living atop copper and gold fields remain among the poorest in the country.

Critics cited in the report contend that foreign investors, from Barrick Gold to prospective U.S. partners, have chosen to ignore issues like enforced disappearances, extrajudicial killings that the locals have been facing in pursuit of resource access.

The report’s contributors, who include journalists, analysts, and investors such as John Zadeh of Discovery Alert and Canadian journalist Lital Khaikin, emphasize that minerals have become a battlefield of narratives as well as resources.

Articles inside trace how China achieved dominance through decades of planning and environmental sacrifices, how the U.S. is seeking alternatives from Australia to Africa, and how Pakistan now figures in Trump’s quest for global mineral security after Ukraine.