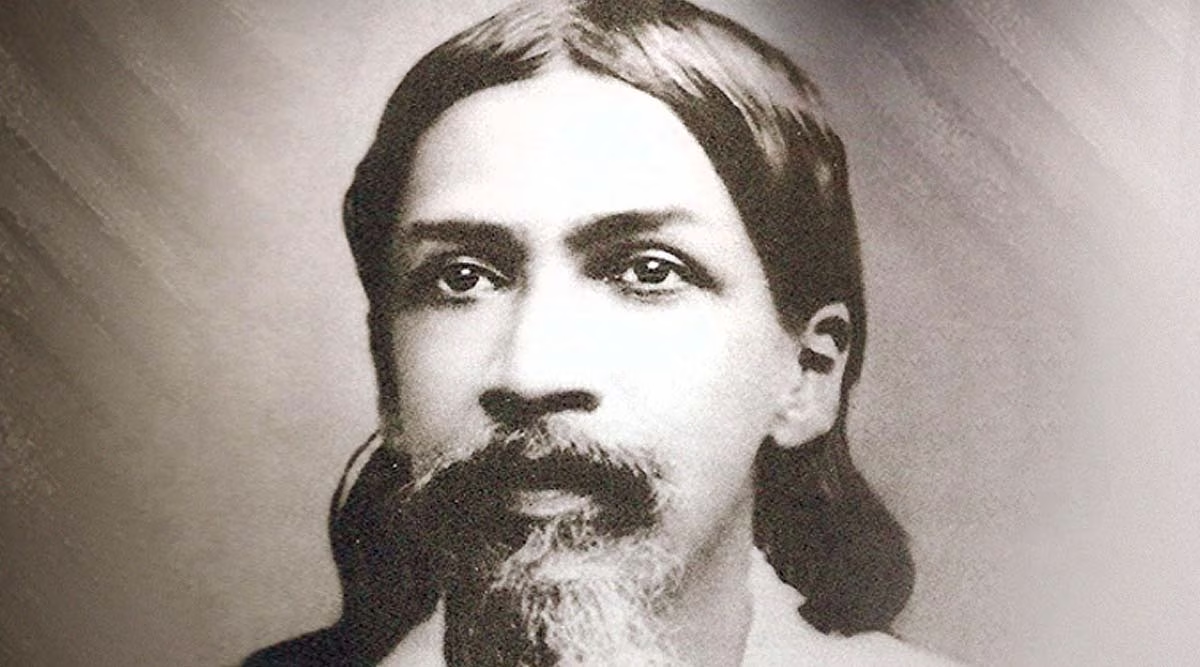

Sri Aurobindo, being part of a long list of personalities, stands apart from them. He was not merely a revolutionary or a nationalist intellectual, but is remembered for his philosophical and visionary insights. He believed that Bharat’s destiny as a nation was tied to the evolution of humanity itself. His idea of “spiritual nationalism” went far beyond the politics of Independence. It was about restoring India’s soul and giving the world a civilizational compass. To read Aurobindo today is to realize that he was way ahead of his time.

He saw that independence, while essential, was only the beginning. Without unity, without dharma, without spiritual grounding, political freedom would be shallow and unfounded. For him, Bharat’s rise was inevitable because it was willed by the “Divine.” Hence, for him, the purpose was not just power but illumination. And for such reasons, we do remember him as the father of spiritual nationalism.

Aurobindo’s greatness gets revealed most clearly after his imprisonment in the Alipore conspiracy case. After he spent a year in solitary confinement (1908-09), reading the Gita and the Upanishads, and undergoing a profound spiritual transformation, Aurobindo emerged as a different person. His return followed the delivery of the Uttarpara speech in May 1909, which must be recalled as a moment that redefined Indian nationalism. In that address, Aurobindo declared that his faith in India’s freedom came not from politics but from a direct spiritual realization.

“When I was in jail,” he said, “I was not only in the company of men but also of God.” He claimed that the Divine had assured him of India’s liberation, as certain as the sun will rise tomorrow. But the speech went beyond prophecy. It placed patriotism on a new foundation: as a form of sadhana. For him, India was not just geography or people, but a living embodiment of Shakti and Sanatana Dharma. This was revolutionary.

Other nationalists invoked religion for moral strength. But to Aurobindo, spirituality was the very essence of nationalism. He warned that if India rose without dharma, it would not be able to survive. It may well again lead India to subjugation through “foreign conquest” and another “invasion.” Independence then had to serve a higher purpose: to remind the world of life’s sacredness and the Divine presence in all beings. The Uttarpara speech was thus not a call for power but for spiritual resurgence. It transformed the vocabulary of nationalism, turning it into a civilizational mission.

Aurobindo’s philosophical project was not a retreat from politics as many Left critics have argued. Rather, it was merely a deepening of his views on nationalism. In Puducherry, over four decades, he developed ideas that remain unmatched in scope: The Life Divine, The Synthesis of Yoga, Essays on the Gita, and Savitri.

At the core was “Integral Yoga” (Purna Yoga), a vision of life where knowledge, action, devotion, and meditation were not separate streams but a single river leading toward the supramental. For him, the goal was not to abandon the world but to transform it by bringing divinity into the texture and sublimity of daily life.

Through his works like The Synthesis of Yoga, where he harmonized centuries of practice into a modern discipline, and through his vision of education, he anticipated a century ago what we today call holistic, valuesbased, and creative pedagogy. These must not remain as side notes but be treated as indicators of Bharat’s philosophical morsel, they would form the very lifeline of a living knowledge system. If IKS is to be more than a cultural slogan, it must give pride of place to thinkers like Aurobindo.

Without him, and without many who bridged tradition and modernity, IKS cannot truly be realized. He demonstrated that Indian knowledge is not about repeating the past but evolving consciousness, individually and collectively. That evolution, as Aurobindo argued, is humanity’s real destiny. To forget him in our curricula and discourses is to weaken the very project of civilizational resurgence.

Why does Aurobindo matter today? Because the challenges that he spoke of, like division, polarization, and materialism, are still here. And arguably intensified. Domestically, his warning about disunity strikes close. He argued that religious and social fractures would cripple India’s rise. Today, caste, community, and ideology often divide us more than they unite us.

For Aurobindo, ‘unity in diversity’ did not mean erasing differences. It meant elevating them toward shared higher ideals. In an India still negotiating its social fabric, his insistence on harmony through dharma is a message we cannot afford to ignore. Globally, Aurobindo’s relevance is even more striking. He envisioned India not as a narrow nation-state but as a civilization with a real mission to embody Sanatana Dharma’s universal spirit, which is openness, inclusivity, and unification.

All of them aimed to guide humanity at a time of crisis. This resonates with India’s role in the G20 presidency, or leadership role in the Global South, where the theme Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam (One Earth, One Family, One Future) echoes Aurobindo’s conviction that nations must cooperate, not compete.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has repeatedly framed India’s rise not in terms of power politics but as a force for harmony and peace—a responsible power. Although adapted to modern diplomacy, this language is deeply Aurobindonian in spirit. Furthermore, even in questions of culture and globalization, Aurobindo was ahead of his time. His call for a “voluntary fusion of cultures” anticipated debates on global interconnectedness.

But unlike the homogenizing pressures of today’s globalization, he envisioned a synthesis that was creative and uplifting. Cultures, he believed, could retain their identities while contributing to a brighter collective future. Finally, at the individual level, his relevance is profound. In an era of social media polarization, mindless consumerism, and widespread anxiety, Aurobindo’s message is that structural reforms are never enough.

True progress begins with the individual striving for discipline, harmony, and higher consciousness. Without inner transformation, outer reforms remain shallow and incomplete. What he offered was a third way: neither escapist spirituality nor unthinking materialism, but a path of integration. His dream of a “divine life on earth” may seem utopian, but it is precisely the kind of compass needed in a fractured world.

In brief, Sri Aurobindo’s legacy rests on three foundations. First, his Uttarpara vision redefined nationalism as a sacred duty and spiritual destiny, lifting it above the ordinary struggles of power. Second, his philosophical contributions, be it Integral Yoga or the evolution of consciousness, offer us a holistic transformation framework. Third, his relevance today is undeniable: in India’s domestic challenges of unity, its educational aspirations under NEP, and its global role through G20 diplomacy and Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam.

To honour Aurobindo is not to place him on a pedestal of history, but to take his ideas seriously today. By incorporating him in IKS, we can perhaps make the first steps to do justice to his contributions. As he argued, independence is merely the first chapter. The greater task lies in realizing his civilizational mission: to unite material progress with spiritual depth and rediscover Sanatan Dharma as a principle of harmony, not dogma. As Bharat rises, the question Aurobindo leaves us with is: rise for what? For power alone, or for illumination? His answer was clear: Bharat must rise not only to be strong, but to be luminous. It should rise as a guide for humanity.

Prof Santishree Dhulipudi Pandit is the Vice Chancellor of JNU.