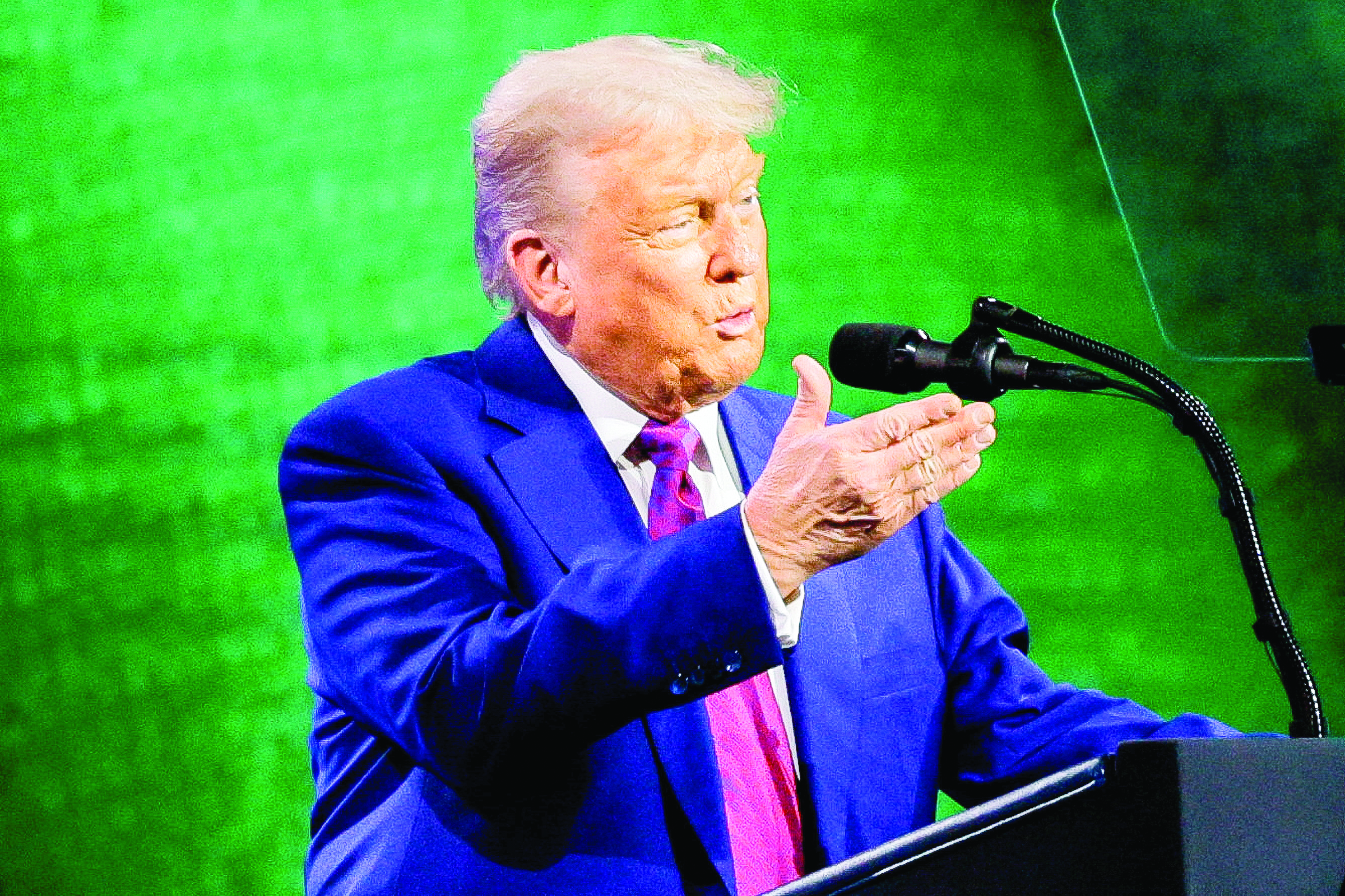

There is little that India can do to check President Donald Trump’s almost daily posts on his own social media app, Truth Social. Through the random thoughts, threats, and occasional executive orders put up there, the site has become the virtual mouthpiece of the Trump 2.0 Administration.

Of much greater significance than this “Trumpian” mode of communication are the actual contents of his mostly stray, half-baked, and only occasionally considered posts. A common characteristic of almost all of them is the reeking mercantilism—the kind that says, “you tell me what you can do for me, and then I will offer what I can do.” Every resultant deal, irrespective of how it is arrived at, is lauded publicly by Trump or his minions.

The situation grew more pronounced when Pakistan, in contrast, credited Trump for the breakthrough and even nominated him for a Nobel Peace Prize for preventing a sharp escalation of the conflict between the two nuclear powers.

To crank up the pressure on Moscow, additional sanctions are being threatened by Trump upon countries continuing to buy Russian oil if Russia does not make peace. Given his marked reluctance to confront China or the EU, India remains the only likely target for this punitive measure.

Going forward, it is imperative for India to not isolate itself from the US or its allies. The national objective of integrating with the global centres of commerce, capital, and technology must remain intact. India needs all these modern factors of production wherever they might be. From time to time, to safeguard its own interests, India would need to counterbalance one so endowed nation against another.

Trump often boasts about his administration’s ability to win big concessions from others. In the case of the BTA with the UK, India had done well to concede on a few red lines. In a similar vein, it must appease Trump by granting him a few such talking points. In non-sensitive agriculture areas, for instance, duty-free imports could be allowed of US apples, almonds, walnuts, soya, and corn oil for producing cleaner fuel. Also, easy import of American spirits like bourbon and Californian wine can be granted.

As of now, the four big suppliers of crude to India are Russia, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. These Middle East nations have held their share in India’s crude imports of four million barrels a day. Till 2024, the discounted Russian crude had come in lieu of purchases from Nigeria, USA, Mexico, Colombia, Ecuador, Gabon, and Congo. Since then, even without any government directive, Russian crude imports have been declining. With increased engagement in sourcing from the US, West Africa, and Latin America, Indian importers are enhancing their energy security and mitigating potential geopolitical risks.