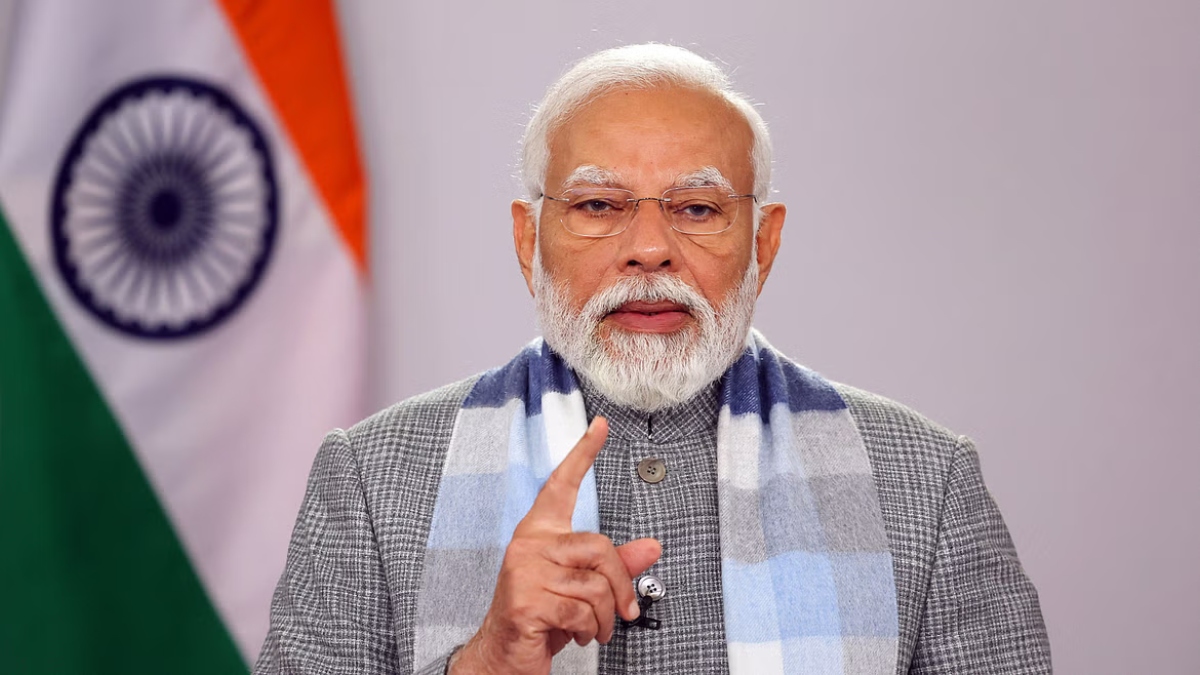

From the time he was sworn in as Prime Minister of India in 2014, PM Narendra Modi has had to navigate geopolitical crosscurrents with dexterity, in the way he had safely navigated political crosscurrents when he was Chief Minister, Gujarat. He needs all that skill now, for the world is witnessing a period of geopolitical war. This is a phrase that has yet to come into common usage, even though geopolitics itself has escaped its earlier obscurity.

When the present writer was invited by Dr M.S. Valiathan, the first Vice-Chancellor of the newly deemed Manipal University, to be the first Professor of Geopolitics in Asia towards the close of 1998, he was initially taken aback. After all, he was not in academics at all but in journalism, in one of the most widely circulated and prestigious publications in the world, the Times of India. After meeting Chancellor Pai and being delighted that he had the same nationalist determination as Dr Valiathan, he accepted and joined in 1999. What we have been witnessing during the present decade is a competition so intense amongst countries as to fit the term.

They are in a state of geopolitical war, a situation evident in the trade, migration and kinetic conflicts going on, as well as challenges such as laboratory-created diseases such as Covid-19. In each, the Prime Minister has shown he is a quick learner, and has handled the situation well. Tariff wars have erupted in a manner not seen for a long time. The leadership in India has been taking remedial action in a quiet manner. At the same time, Indian companies have been working to ensure that they are protected against much of the impact, and part of such remedial action has been the setting up of offshore subsidiaries. Given the geopolitical situation, the risk in depending on active or potential hostile powers for several key imports, thereby providing them with the very surpluses they could deploy in activities by themselves or by other countries hostile to India is obvious.

The trade deficit with China, in particular, needs to be reduced substantially through development of indigenous capability and through securing alternative countries for supplies. The just concluded foreign tour of Prime Minister Modi was a textbook example of such efforts. The visit was very successful in identifying potential alternatives. Now what is needed is to take the next steps and make such changes operative. In the past, India has been characterised by good starts followed by inadequate follow-up.

The HF-24 Marut is a lesson from the past in this regard. Had it not been quietly scuppered by the import lobby, by now India would have been among the largest producers and exporters of aircraft. Shifts in geopolitical currents have made the road ahead a minefield, and it is on such a road that Prime Minister Modi is traversing. Progress has been steady but watchfulness is ever needed. The whole world is watching the journey of India into becoming the third superpower, and friends and partners need to be mobilised to help ensure success.

By 2029, India must change from a net importer into a net exporter, and although the task is difficult, it needs to be attempted.