Anandamath, Sanyasi resistance, and the Hindu awakening

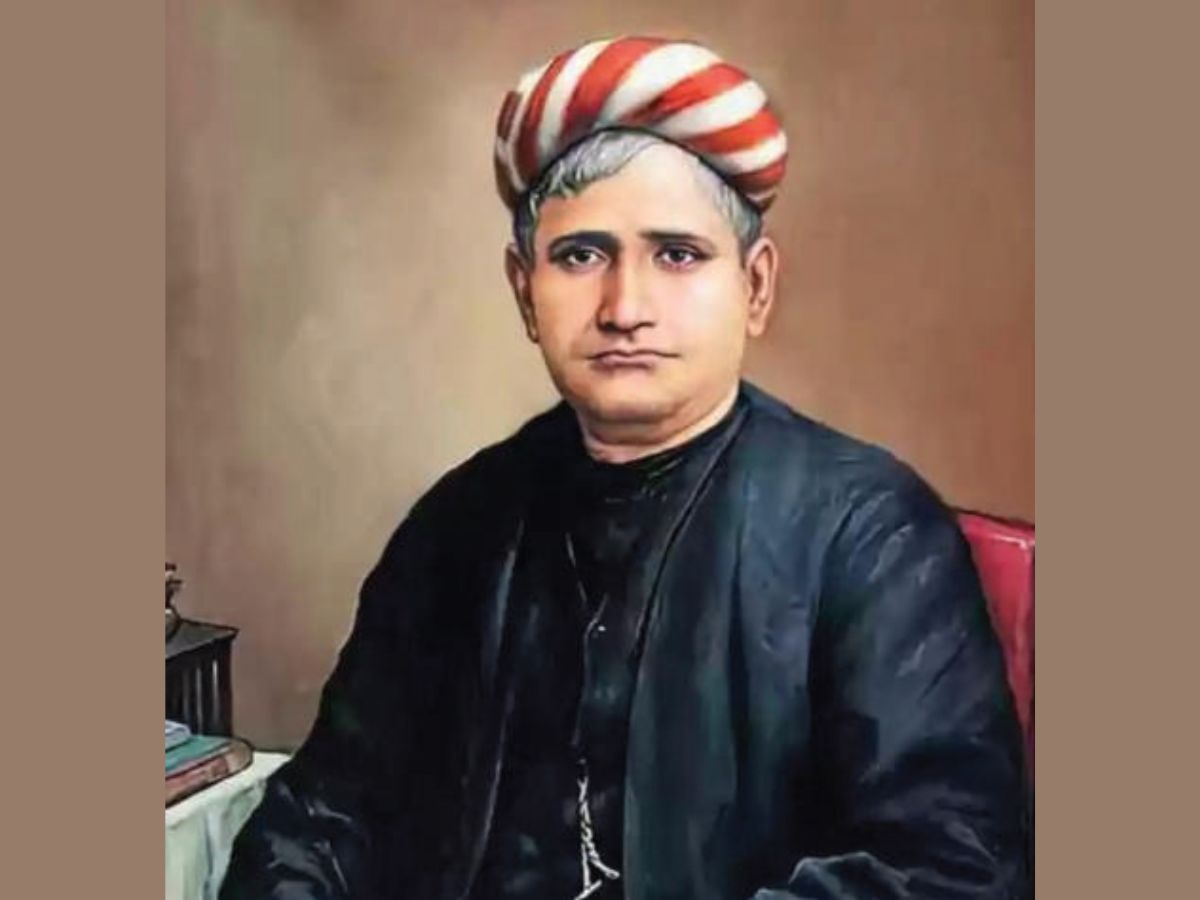

Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay (Image: File)

“Vande Mataram is the modern embodiment of a great cultural tradition," said PM Modi. He underscored that Bankim Chandra composed lines which emphasised that Mother India is both the goddess of knowledge and prosperity, and also the fierce Chandika who wields weapons against enemies.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi recontextualised the relevance of Vande Mataram while celebrating its 150 years since it was written. Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay is too often read narrowly as a nationalist novelist, and his momentous contribution, Vande Mataram, is too conveniently confined to the freedom struggle. Both readings are historically shallow and incomplete.

Bankim was not merely reacting to British colonialism but also responding to a much older and more profound civilisational unease. In this sense, Anandamath was not a political novel in the modern sense, but rather a cultural and spiritual call to awaken a Hindu society that had forgotten how to defend itself. The novel is rooted in the Sanyasi rebellion of the late eighteenth century. These were not imagined revolutionaries or romantic rebels inserted retrospectively into nationalist history. They were warrior-sanyasis—ascetics who took up arms when Hindu religious institutions, pilgrimage networks, and agrarian livelihoods were being systematically disrupted by exploitative revenue systems and political predation. Their resistance was instinctive, civilisational, and defensive, unlike many who assume it as ideological in the modern sense.

More importantly, unlike many contemporary terminologies, it is essential to understand that the warrior-sanyasi was not a colonial invention. Its lineage can be traced back centuries to the Akhara system, traditionally attributed to Adi Shankaracharya. Shankaracharya did not organise monastic orders merely for metaphysical debate. He understood that civilisation survives not only through philosophy but also through discipline, organisation, and the capacity for self-protection. The akharas institutionalised this balance between ascetic restraint and martial readiness.

Seen in this light, the sanyasis of Anandamath are not anomalies or extremists. They are historical continuities. Bankim’s genius lay in recognising this and giving it literary form. His sanyasis are disciplined, detached from personal desire, and bound by duty to the Mother. They are not fighting for political power or personal gain. They are fighting for the survival of a civilisational order that had been steadily eroded.

And it is within this narrative that Vande Mataram must be located. In Anandamath, the song functions unmistakably as a war cry. It is a call to awaken a society lulled into passivity, fractured by internal divisions, and resigned to decline. To restrict Vande Mataram to the freedom struggle alone is to amputate its deeper meaning.

The song was not born in Congress sessions or constitutional debates. It emerged from a Hindu civilisational reawakening taking shape under colonial conditions. This distinction is important because the 19th century was not merely an era of anti-colonial politics. It was a period of intense cultural churn, especially in Bengal. The so-called Bengal Renaissance was not only about reform or Western education, but also about regaining civilisational confidence after centuries of cultural dislocation.

Hindu society was forced to confront an uncomfortable question: how does a civilisation modernise without dissolving itself? Figures as diverse as Raja Rammohun Roy, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, Ramakrishna Paramhans, Vivekananda, and later Aurobindo Ghosh responded to this dilemma in different ways. They disagreed profoundly on method, theology, and reform, but they shared a common concern: Hindu society had lost its self-belief. It needed renewal, not self-erasure.

In here, Bankim’s intervention was neither reformist nor reactionary in the conventional sense. He did not go and argue through treatises or sermons. Instead, he spoke through myth, symbol, and emotion. Where reformers petitioned, and saints preached, Bankim invoked the Mother. The Mother in Vande Mataram is an idea and even an emotion that cannot merely be understood through the label of land or territory. She is culture, she is memory, she is continuity, and she is strength. In fact, she is the civilisation itself, imagined in feminine form.

This invocation is not accidental, as Hindu civilisation has long located moral force and protective power in the feminine. Durga is not passive or ornamental. She is valour, courage, and righteous destruction of evil when restraint fails. By invoking the Mother, Bankim was not appealing to sentimentality but instead calling for resolve. Vande Mataram, hence, does not just describe the Mother. It calls for remembrance, recognition, and rejuvenation of her ideals.

This is precisely why contemporary claims in Indian political discourse that assert the song to be exclusionary turn out to be hollow and atypical. The Mother invoked in Vande Mataram is not a sectarian deity demanding ritual submission. She is the universal civilisational principle that calls people to rise above narrow divisions. And only a half-baked reading would interpret an invocation of the Universal Mother as alienating. The song does not ask what faith one follows, but it does ask whether one recognises the civilisation that sustains them.

Because civilisations are not sustained by procedures. They are sustained by shared symbols that transcend individual belief. To deny this is to misunderstand how societies endure. Vande Mataram belongs to that category of civilisational symbols—older than the modern nation-state, deeper than political slogans, and more enduring than temporary controversies.

It is also essential to recognise that Anandamath and Vande Mataram were products of a time when Hindu society was emerging from prolonged vulnerability. They reflect a defensive assertion, not a desire for domination.

The sanyasi in Bankim’s imagination renounces personal life to serve the Mother. This is not triumphalism, but an admission and acceptance of the sacrifice itself.

In recent years, references to Vande Mataram, akharas, and civilisational memory by India’s political leadership have triggered predictable unease. But such references are better understood as reminders of continuity rather than instruments of coercion. India did not appear suddenly in 1947. It has existed before most modern nation-states existed. The idea of Bharat rests not in some declarations or treaties, but in older moral and cultural foundations. And to acknowledge them is honesty, not regression.

Yet, we need to understand that remembering and honouring our symbols should not mean that we freeze symbols in time. Nor does it mean that we weaponise them in politics. Instead, it is through these symbols, imagery, and works like Anandamath that we spell out truth and meaning by reaching out to historical depths. Anandamath should not be sanitised to fit contemporary comfort, nor should it be demonised to suit ideological hostility. It should be read for what it is: a literary expression of Hindu awakening during a moment of existential uncertainty.

Vande Mataram remains relevant today because it has spoken to something deeper than our political allegiances or individual preferences. It has spoken to our civilisational memory of loss, resistance, renewal, and continuity. It serves as a poignant reminder to society that self-respect precedes freedom, and cultural confidence precedes political assertion. To re-read Bankim honestly is not to retreat into the past but to understand the foundations on which modern India stands.

Because bluntly told, a civilisation that remembers itself clearly does not fear debate, but it only fears amnesia.

Prof Santishree Dhulipudi Pandit is the Vice Chancellor of JNU.