Bhyrappa’s moral universe extended beyond literature. He saw himself not merely as a storyteller, but as a custodian of civilisational truth.

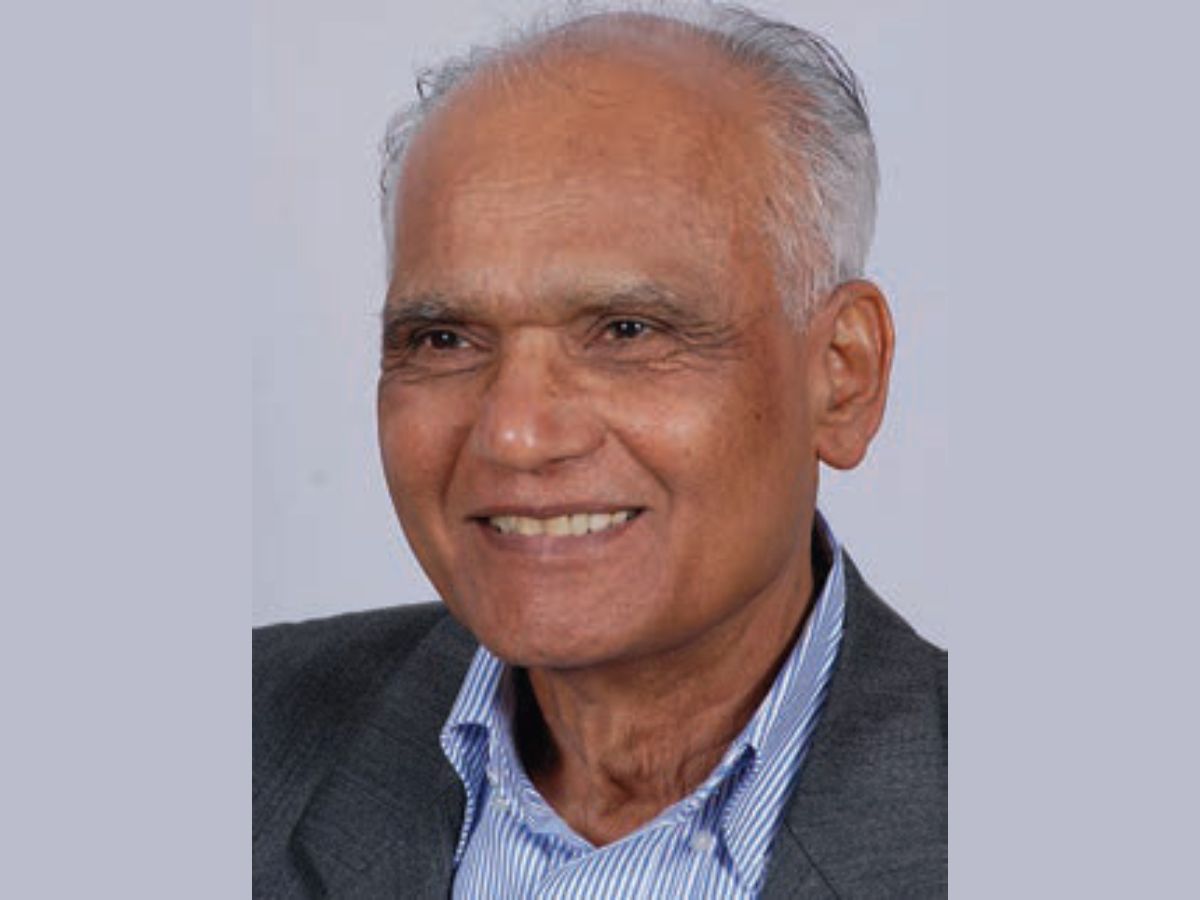

Few people defy time and influence lives with such conviction and clarity that they become a moral compass for generations to come. Santeshivara Lingannaiah Bhyrappa was one such life. His passing at ninety-four is not merely a literary loss but a moment of remembrance of a thinker who stood unbent when conformity was rewarded, who wrote of truth when truth had few friends.

A LIFE OF ADVERSITY

Bhyrappa’s story began far from the clamour of literary salons or intellectual circles. Born in 1931 in the quiet village of Santeshivara in Karnataka’s Hassan district, he tasted loss before he learnt language. The plague claimed his mother and brother; his father, erratic and indifferent, offered little refuge. Education became both refuge and rebellion. He went on to complete his philosophy degree at Mysore University with distinction. He later pursued a doctoral thesis on aesthetics, Satya Mattu Soundarya (Truth and Beauty), a pairing of ideas that defined his intellectual compass throughout his life. Before he became a novelist, Bhyrappa was a teacher. Starting off in Karnataka, later with NCERT in Delhi, and finally at universities in Gujarat and Mysore. For him, teaching was not a profession but a sacred calling, as he believed the transmission of knowledge was a duty, an ethical act that illuminated the world. He combined this moral seriousness with the discipline of a philosopher and the imagination of a writer. This quality was later clearly manifested in his novels.

A PHILOSOPHER NOVELIST

If philosophy grounded Bhyrappa, literature set him free. His novels were not mere stories, but journeys through myth, morality, and the metaphysics of human choice. Across more than two dozen works, he displayed a rare blend of intellectual precision and artistic daring. His early work, Vamshavriksha (The Family Tree), explored the tension between generational duty and social norms, as tested against ideas of individual freedom and personal fulfillment. This theme resonated with the modernizing India of the 1960s. The novel’s cinematic adaptation by B.V. Karanth and Girish Karnad became a landmark in Kannada cinema. Grihabhanga (The Breaking of a Home) tells the story of a woman struggling against her husband and his family in rural India. It was partly autobiographical as it was inspired by his own mother’s life. In all of these stories, Bhyrappa did not sentimentalise pain but treated it as the crucible of self-discovery.

Then came Parva (Epoch) (1979), another notable achievement in intellectual work. It was a radical retelling of the Mahabharata. Here, Bhyrappa reimagined epic heroes as flawed humans wrestling with questions of dharma, power, and fate. It discussed the phenomenon of war in a philosophical sense while also adopting a rational view of war. In such a sense, it was less mythology and more of an intellectual reflection of India’s eternal debate between duty and desire. For such reasons, Parva remains one of the most outstanding literary achievements in modern Indian languages. In Mandra, which won the Saraswati Samman, Bhyrappa drew on Indian classical music to explore the aesthetics of passion and the discipline of art in a story centered on musicians. His other work, Sartha (Caravan) (published in 1998), was a philosophical journey through ancient India that included figures such as Adi Shankaracharya. It was a meditation on the decline of wisdom and the search for renewal. In Tantu (Cords), he examined the erosion of moral values in the post-Independence period and the dark chapter of Indian history, the Emergency. Meanwhile, in Uttarakanda, he reinterpreted the Ramayana through the eyes of Sita. Also referred to as Sita’s “soliloquy,” this work gave voice to Sita, who had long been overlooked by various canonical works.

But it was Aavarana (2007) that became both his lightning rod and his legacy. Ostensibly a story of a Hindu woman who marries a Muslim man and later discovers the layers of historical concealment around her, the novel was, in truth, a searing confrontation with India’s collective amnesia. Its title means “veil,” and Bhyrappa used it as a metaphor for the ideological distortions of Indian history. He wrote with meticulous research and moral urgency, laying bare how truth had been hidden to suit the political fashions of the day. Critics called Aavarana communal, but to readers curious to know India’s past, it was courageous. It went on to become one of the most widely read novels in the Kannada language. It was translated into several languages and sold tens of thousands of copies. But what made it powerful was not polemics but the sincerity of Bhyrappa in refusing to surrender the narrative of India’s past to the guardians of ideology.

All through his career, Bhyrappa steered clear of literary factions and ideological caucuses. The Navya modernists, the Bandaya rebels, and the Dalit movement writers all sought to define Kannada literature through their ideological frames. Bhyrappa belonged to none. He walked alone, guided by his inner compass. This independence made him a target of criticism, but also a beacon for readers who sought intellectual honesty over fashionable slogans. He epitomizes the kind of courage that endures long after applause fades: the lonely courage.

SENTINEL OF CULTURE AND CIVILISATION

Bhyrappa’s moral universe extended beyond literature. He saw himself not merely as a storyteller, but as a custodian of civilisational truth. His engagement with the ideological distortions of history began decades before the term “culture wars” became a public phenomenon. As a member of the National Integration Committee chaired by JNU’s first Vice-Chancellor, G. Parthasarathy, he protested the Left’s attempts to sanitise textbooks and whitewash the record of invasions and cultural suppression. For that dissent, he was replaced by a more pliant scholar. But he never yielded. Long before the Ayodhya debates exposed the fault lines in academia, Bhyrappa had witnessed the machinery of “history fixing” at work, and he did not remain silent; instead, he chose to speak. Aavarana was born of that experience. Through its protagonist’s quest for truth, he exposed how entire generations were taught to distrust their own civilisation. He questioned why temples destroyed were forgotten, why heroes were vilified and invaders romanticised, and why any attempt to reclaim cultural memory was branded as regressive. For him, history was not vengeance, but a pursuit of justice for the truth. He once wrote that “the act of concealing truth is aavarana, and that of projecting untruth is vikshepa.” In those two Sanskrit words lies his lifelong battle to unveil and restore truth.

In an age when speaking of civilisational continuity invited derision, Bhyrappa stood tall. He believed that India’s cultural inheritance was not a relic but a living force. For him, it was too sacred to be mutilated by transient ideologies. He engaged in cultural defence long before it became part of the national conversation. While many intellectuals bent to the prevailing Left-liberal consensus, he held his ground with quiet authority. His works became rallying points for those who sought to reclaim India’s civilisational confidence, the same spirit that now animates efforts under the Indian Knowledge Systems (IKS) movement. In that sense, Bhyrappa was not just a novelist but a harbinger of India’s cultural renaissance.

COURAGE TO BE ALONE

S.L. Bhyrappa lived simply and wrote truthfully. He never sought the comfort of consensus or the refuge of institutions. His readers ranged from professors to ordinary people who adored him not because he said what they wanted to hear, but because he spoke truth while respecting their intelligence. For Bhyrappa, his politics reflected his integrity. He was the rare intellectual who saw beauty as truth and truth as beauty. Both to him were inseparable, indivisible, and sacred. Long before the term “cultural revival” became fashionable, he was its quiet architect. He demonstrated that defending culture is not chauvinism, but instead honouring the past. Bhyrappa stood alone when silence was safer. And because he did, India today stands a little taller, our civilisation a little more self-aware, and a little less ashamed of its truth.

Prof Santishree Dhulipudi Pandit is the Vice Chancellor of JNU.