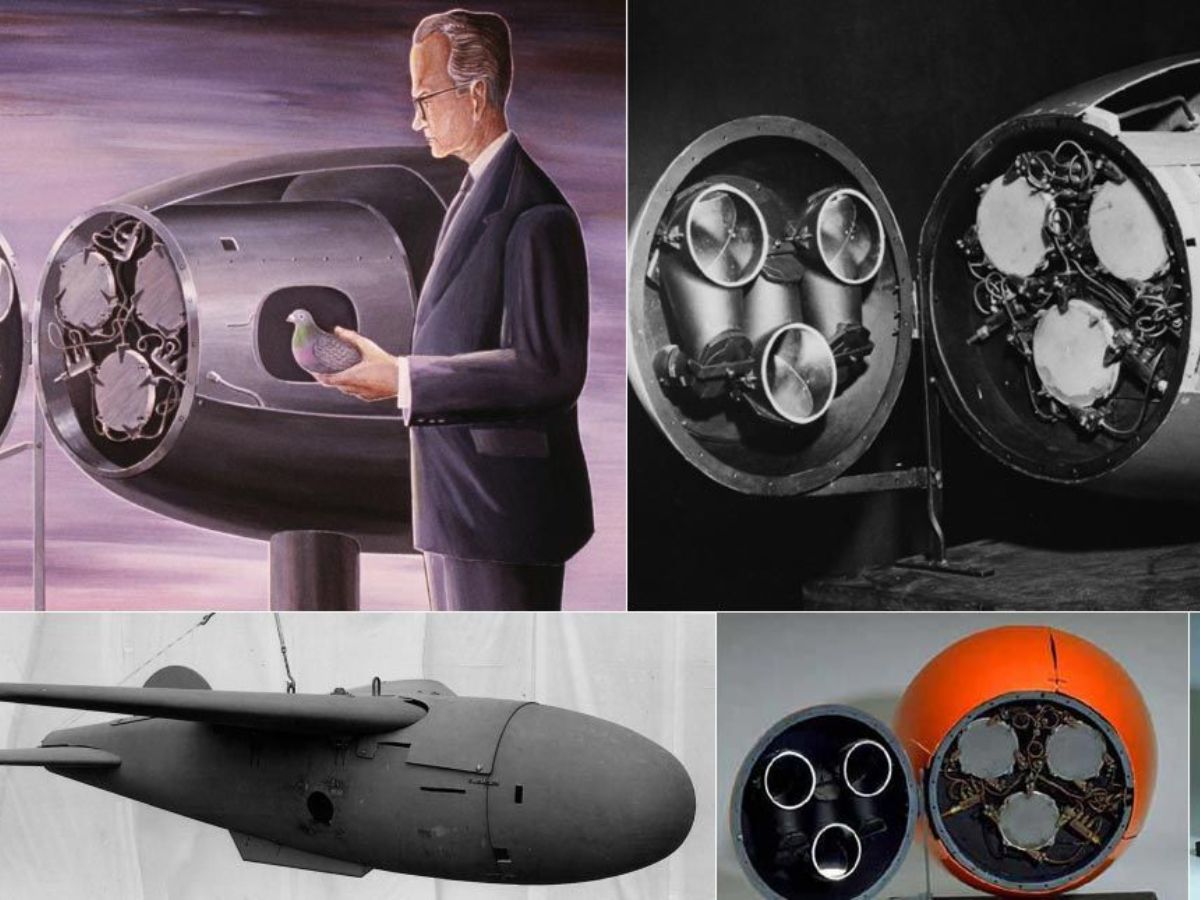

During World War II, the US military funded one of the most absurd experiments in defence research, Project Pigeon. Conceived by the psychologist B.F. Skinner, the idea was to train pigeons to peck at the image of an enemy ship projected inside a missile’s nose cone, thus steering the bomb toward its target. The birds performed flawlessly in trials. Yet the Pentagon balked at trusting a $25,000 warhead to a pigeon. The project was quietly abandoned, ingenious in design, but irrelevant in outcome. It is a story that perfectly captures the perils of mistaking experimentation for impact.

As India begins to invest more heavily in research and frontier technologies, it becomes important how well we can trace what that spending actually achieves. Thousands of projects are financed annually, but few can be traced to products, policies, or patents that transformed markets. A filed patent is not commercialisation. A prototype is not adoption. What India lacks is a theory of change, a system to causally link research inputs to national outcomes, supported by a digital infrastructure that can measure, monitor, and enable course correction.

A credible theory of change begins with five traceable stages, inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes, and impact. Inputs are grants, infrastructure, and talent. Activities encompass experimentation, design, and testing. Outputs are tangible results, papers, patents, standards, prototypes. Outcomes should gauge whether the innovation diffused, reduced import dependence, or generated jobs. Impact captures structural transformation. Has it strengthened sovereignty, competitiveness, or resilience? This causal chain should be the operating code of Indian science policy, not an afterthought in evaluation reports.

At the outset, one must also recognise that failure is intrinsic to scientific progress. To treat every failed hypothesis as a loss is to misunderstand the epistemology of discovery. The value of R&D lies not only in success but in the informational content of failure, the data it generates, the assumptions it tests, the pathways it eliminates. Mature innovation systems institutionalise these learning loops. The real dysfunction arises when failures go unrecorded, unanalysed, and unlearned, when resources vanish without producing either knowledge or capability. The task is to distinguish productive failure that refines understanding from unproductive drift that dissipates value, ensuring even what fails contributes to cumulative national competence.

Globally, R&D programmes follow two distinct pathways of impact. The first produces a product or service, where outcomes are measured through diffusion and economic contribution. The US ARPA-E tracks how many technologies reach markets, how many startups emerge, and how much capital they raise. Horizon Europe measures job creation, firm growth, and investment leverage. The US NIH mandates that every funded clinical trial report downstream health outcomes. The second pathway advances Technology Readiness Levels (TRLs) without immediate commercialisation, where impact lies in capacity-building: new methods, datasets, standards, and trained researchers. The NSF counts new labs and collaborations formed; Horizon Europe monitors human capital and post-project investments as medium-term indicators, and prototypes or demonstrators as short-term outputs.

In India, these pathways are not systematically captured. Patents are logged in one database, citations in another, startups elsewhere. No ministry can answer how much of its R&D budget translates into new products, technologies, or skilled researchers. A dual-pathway framework could fix this. For product-stage projects, track commercialisation, follow-on investment, and mission-linked outcomes such as energy saved or patients reached. For early-stage research, track TRL advancement, human capital created, and infrastructure built. A “Research Impact Dashboard” could integrate these indicators across ministries, linking money spent to capability created.

To operationalise this transformation, India needs a Digital Public Infrastructure for innovation, an “Innovation Stack” (developed by Foundation for Advancing Science & Technology [FAST-India]) that does for research governance what UPI did for payments. Today, managing a grant means navigating PDFs, portals, and paper trails. The Innovation Stack would standardise how grants, reviews, procurement, and reporting are encoded (standards layer), connect agency and institutional systems through open APIs (integration layer), and build atop Aadhaar, DigiLocker, GeM, and Account Aggregator (infrastructure layer). This would turn India’s fragmented R&D ecosystem into an interoperable, algorithmically governed system, enabling instantaneous visibility into fund flows, procurement bottlenecks, and outcome metrics.

Once embedded, the Innovation Stack becomes the plumbing of accountability, transforming opaque discretion into rule-based workflows. Researchers could auto-discover calls for proposals and track grants in real time. Agencies could link funding data with patents, startups, and TRL progression, allowing granular attribution of results. For policymakers, it would finally make R&D measurable, comparable, and optimisable.

India’s R&D policy must now shift from grant disbursal to impact governance. That means evaluating portfolios rather than projects, rewarding outcomes instead of outputs, and shifting from static reporting to dynamic monitoring. When feedback and learning replace ritual compliance, the system will begin to reward what works and reform what doesn’t.

A mature research ecosystem does not simply fund discovery. It converts discovery into national capability. A theory of change, reinforced by a global dual-pathway impact model, guided by a culture of productive failure, and powered by a digital Innovation Stack, can turn India’s scientific expenditure into a genuine instrument of transformation. Otherwise, we might also risk building an innovation missile and letting the pigeons fly it.

Aditya Sinha writes on macroeconomic and geopolitical issues. Aparajita Marwah is a public policy professional.