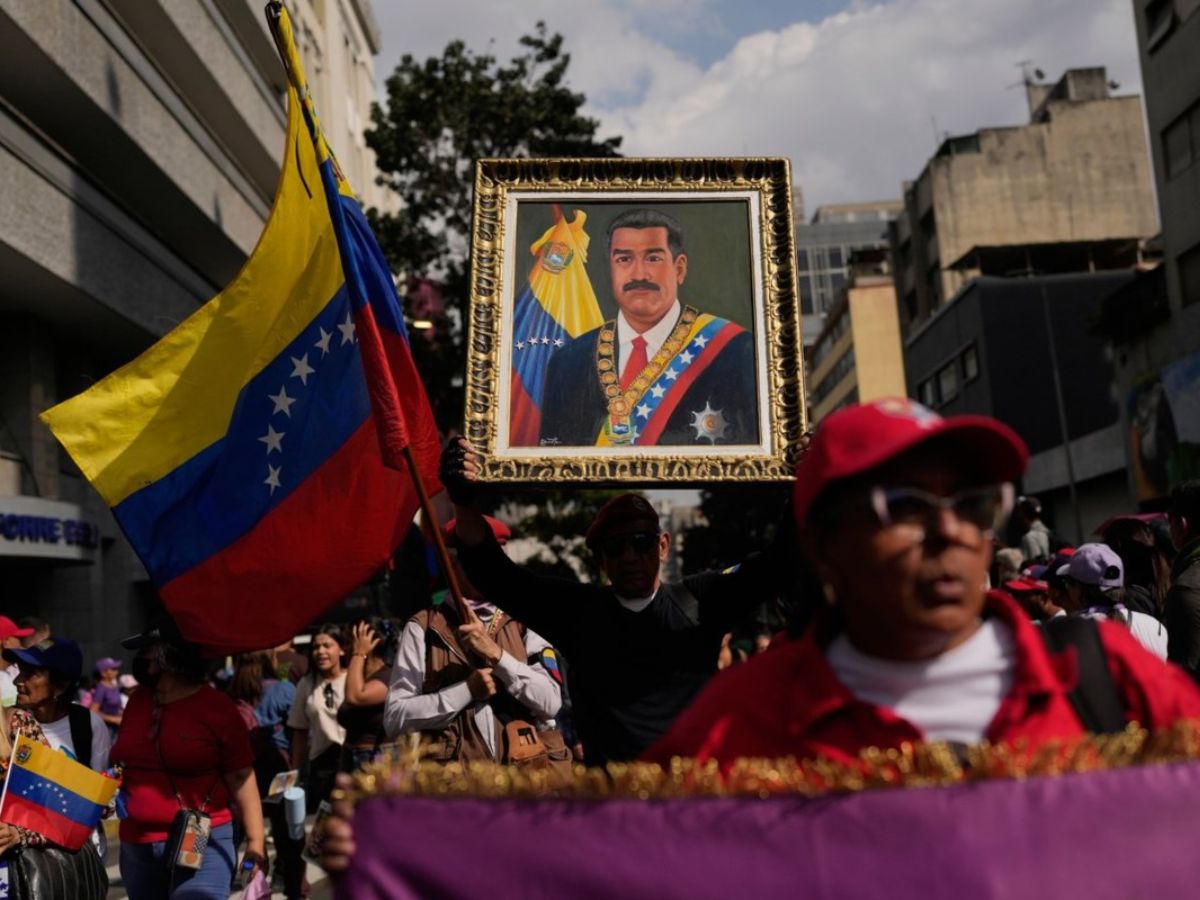

Is this the end of the rulesbased order? Or should we ask if this is the end of the illusion that the world ever truly operated under a rules-based system? The recent US intervention in Venezuela should be read less as an aberration and more as a declaration. Regime change, coercive intervention, and strategic engineering of sovereign states did not begin in the 21st century, but are being perfected through technological advancements and media (and social media) narratives.

Since World War II, regime change through coups, assassinations, proxy conflicts, and direct military interventions have been routine instruments of power. What is different now is not the act itself, but the absence of discomfort in using them. Power no longer feels compelled to justify itself at length. It acts, and the world adjusts. Europe issues statements. Institutions issue reminders. Markets respond, and life moves on.

This is not a rules-based order because that presupposes certain rules that apply to all. And this system today is not adhering to any. If anything, it is implementing them depending on convenience. World politics today has turned into an arena that is hierarchical, unequal, and increasingly brazen about it. When a major power decides that its interests are sufficiently vital, rules become decorative. International law is acknowledged in passing, if at all. And then, all rules are sidestepped. The possibility that Greenland could be next is no joke or provocation, but as many commentators put it, a matter of time. Geography, resources, and leverage matter more than precedent. Who needs principles when strategic advantage is on the table?

Energy security sits at the core of this recalibration by the US. Strip away the rhetoric, and what remains is a hard, yet unsentimental logic. Control over energy is control over the tempo of economic, military, diplomatic, and even cultural trends. If the US succeeds in exerting decisive influence over Venezuela’s largest proven oil reserves (which it is likely to do), then, by extension, it will have enduring benefits. Because such control reduces vulnerability elsewhere and enables insulation against shocks in the Persian Gulf.

Let’s not forget, energy is not just fuel but also a leverage. It determines who can endure prolonged conflict and who cannot, who can absorb escalation and who must de-escalate. Access to heavy crude under friendly control reshapes calculations far beyond Latin America. It affects postures in the Middle East, negotiations with rivals, and the stability of global markets. It reinforces the dollar’s centrality in energy trade and, by extension, the financial architecture that underwrites American power.

In this sense, Venezuela is not the story but merely a demonstration. This is why the episode matters. It establishes a precedent that economic pressure, political engineering, and force can be combined to restructure sovereign states when the strategic payoff is sufficiently high. The vocabulary of democracy then becomes secondary. And the power becomes primary. Once such a precedent is set openly, others will learn from it, either to emulate it or to guard against it.

Nonetheless, power is a double-edged sword. Entanglements have costs as prolonged engagement drains political capital, stretches military and economic resources, and narrows room for manoeuvre elsewhere. If pressure hardens into protracted instability, the very flexibility that energy control promises may erode.

This pattern is visible across theatres, be it the Russia-Ukraine War or Iran in the Middle East. These incidents have already demonstrated how quickly energy considerations reorder moral hierarchies. Principles were loudly proclaimed by many European political elites, but when it came to dependencies, they were quietly managed or hushed up. Europe discovered, belatedly, that values do not heat homes or power factories. The resulting scramble, sanctions alongside exemptions, denunciations alongside recalibrations, exposed the gap between rhetoric and reality. Energy did not disappear from geopolitics but ended up reasserting itself as the axis around which choices revolved.

The same duplicity marks Western engagement elsewhere. European states that lecture others on restraint and norms have a long record of intervention, from Iraq to Libya, undertaken with confidence and little accountability. Today, some of those same states criticise countries like India for purchasing Russian oil, even as they continue to benefit indirectly from global energy flows, including refined products processed through Indian infrastructure. The circle is completed quietly, while the sermon continues to be loudly aired on international platforms.

Meanwhile, India, protecting its security interests against the brutal terrorist attack in Pahalgam last year, was viewed as a disruption of peace by the West. The preaching and pontification started well before India carried out Operation Sindoor to assert deterrence against the terrorists operating from and through the support of the Pakistani state. Yet, when the UK and France send arms to Ukraine, they are not considered disrupting or fuelling the fire.

Then there are examples like Canada, whose posture fits neatly into this pattern. For some time now, Canada has claimed the moral high ground while undermining India’s legitimate security concerns by offering space, legitimacy, or silence to extremist elements hostile to Indian sovereignty. When India asserts its right to protect its citizens, it is accused of excess. When major Western powers act decisively to neutralise perceived threats abroad, it is framed as a responsibility. The difference is not in the act, but in “who” performs it.

For India, this moment demands sobriety, not sentimentality. The lesson is not that principles are irrelevant, but that principles without power invite vulnerability. India cannot afford naivety in an era where energy, territory, security, and coercion are once again openly weaponised. Strategic autonomy requires the capacity to defend interests unflinchingly, whether those interests concern energy security, territorial integrity, or the safety of Indian citizens targeted by terrorism.

India does not have a historical record of invading others to reorder societies or extract resources. Its strategic culture has been shaped by endurance, negotiation, balance, and inclusivity in governance. This should not be understood as passivity, but rather as the ability to calibrate one’s actions. Moving ahead, India will need to defend itself firmly, decisively, and without apology when its interests are threatened. But it need not dress that defence in civilisational superiority or moral absolutism. There is a difference between “being strong” and “being hegemonic”. There is a difference between deterrence and domination.

Energy security will increasingly test this balance. As competition intensifies, pressure to align, isolate, or conform will grow. India’s challenge is to diversify without dependency, engage without subordination, and build resilience without provoking unnecessary confrontation. This requires investment, strategic patience, and clarity about red lines. It also requires resisting the moral blackmail that often accompanies geopolitical competition.

The liberal order did not collapse because it was attacked. It collapsed because it was selectively applied. Venezuela, Ukraine, Greenland, Iraq, and Libya are all chapters of the same story. Power was never absent, only masked. That mask has now slipped. What replaces it will not be gentler, only clearer that the age of pretence is over. The world has entered a phase where power speaks plainly, and institutions struggle to keep up. In such a moment, the task for states like India is neither to moralise nor to retreat, but to adapt without losing themselves. Strength must be real. Restraint must be intentional. Principles must be lived, not preached.

History has returned, not as tragedy or farce, but as a painful reminder. The question is not whether states will act in their interests. They will, but whether they can do so without pushing the system toward exhaustion. India’s opportunity lies precisely in navigating this tension: to be strong without being reckless, autonomous without being isolated, and powerful without becoming what it has never been.

What January 2026 has done so far is not to rupture global politics, but to strip it of its contradictions. The language of norms, ethics, and institutional restraint has finally fallen away. It has revealed a familiar and uncomfortable truth: global politics has returned to a state of brute force and realpolitik. “Might is Right” has again become an operating principle of international politics.

-

Prof Santishree Dhulipudi Pandit is the Vice Chancellor of JNU.