When Indians today think of medieval history, they think of the Mughals. The entire period has been reduced to them, as if no other kings, no other civilizations, no other achievements existed in those centuries. This is not an accident. It is the outcome of decades of selective history-writing, where Mughal grandeur was glorified, their cruelty sugar-coated, and their failures whitewashed, while rulers from other parts of the country were either erased or buried under the weight of colonial and leftist constructs. This distortion has left generations of Indians misinformed about their own past and robbed them of the confidence that comes from knowing the full breadth of civilizational achievements. To correct this imbalance, it is necessary to revisit figures like Raja Marthanda Varma of Travancore, whose reign shows us a different story of medieval India: one of resilience, strength, and vision.

THE LOST LEGACY

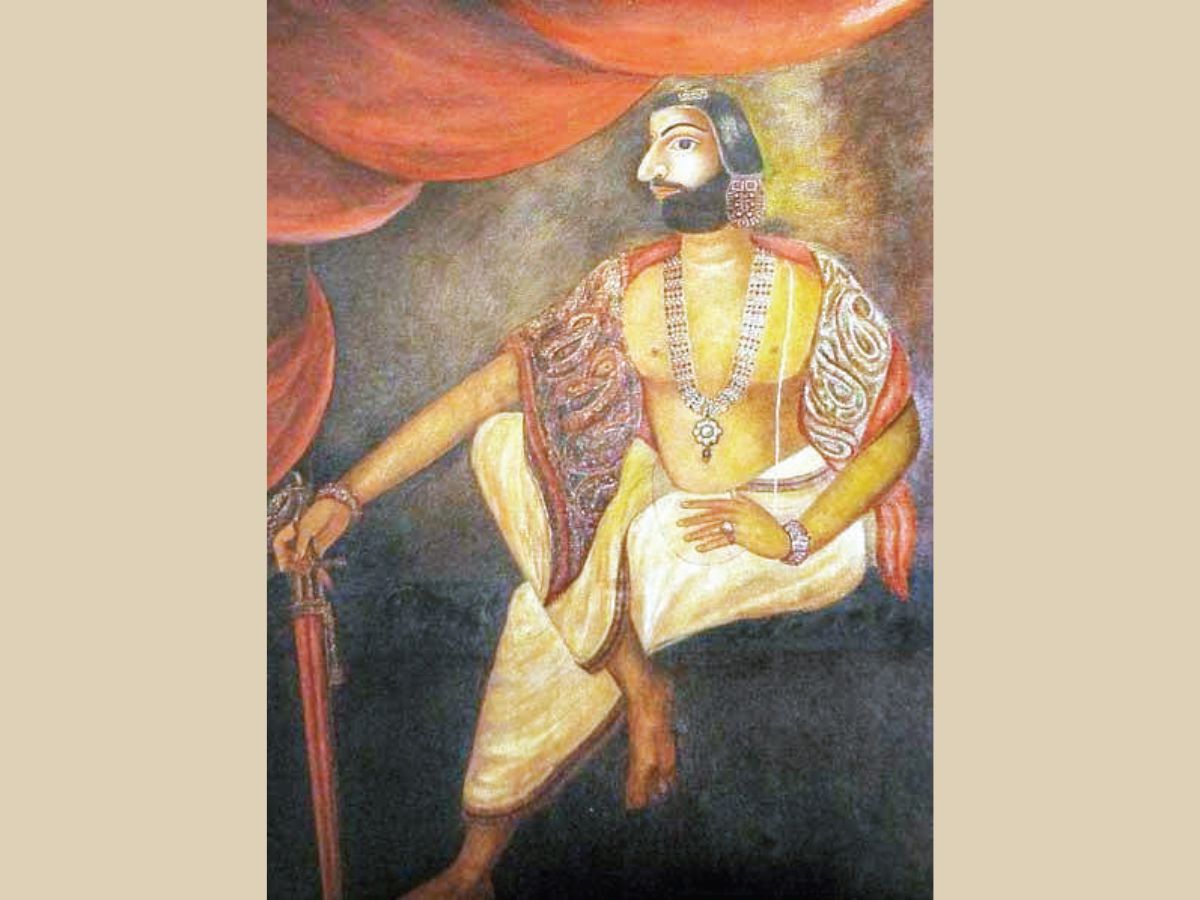

Anizham Thirunal Marthanda Varma (1706-1758) hardly finds a mention in the mainstream narratives of India’s past. And yet, he was the monarch who, in 1741, defeated the Dutch East India Company at the Battle of Colachel. It was the first time an Asian ruler decisively defeated a European colonial power. It was a victory that not only ended Dutch ambitions in India but also proved that Indians could fight and win against colonial invaders. Still, school textbooks remain silent about him, continuing instead with endless chapters on the Mughals. The consequence is that Indians grow up believing their ancestors were forever defeated, their kings incapable, and their kingdoms fragile.

This is the deeper problem of historical teaching in India. The deliberate overemphasis on Mughal rule has created the impression that the medieval period was only about their palaces and patronage. What is left unsaid is their destruction of temples, their imposition of religious taxes, their violent campaigns against native traditions, and the humiliations inflicted on local populations. By glorifying the Mughals and erasing regional kings like Marthanda Varma, leftist historians did not just distort facts, but they also weakened India’s civilizational memory. It is no surprise then that so many Indians remain underconfident about their own history, unsure of what their ancestors achieved. The first step in correcting this is to tell the stories of those like Marthanda Varma, who refused to bow before either feudal rivals or foreign colonizers, and who built something enduring out of chaos.

ACHIEVEMENTS OF A VISIONARY RULER

When Marthanda Varma inherited the throne of Venad in 1729, the state was in disarray. Feuding nobles, known as the Ettuveetil Pillamar, exercised more power than the king himself. Foreign companies like the Dutch meddled in local politics, extracting privileges and squeezing rulers into submission. In such a climate, many rulers gave in. Marthanda Varma did not. He dismantled the power of the local aristocracy with iron resolve, centralised authority, and declared that the crown alone would rule.

His military reforms were equally striking. He revived Kalaris in villages, expanded the Travancore army into a formidable standing force, and fortified his kingdom with the Travancore Lines. The Battle of Colachel showed the fruit of this vision. The Dutch arrived overconfident, sure that their guns and European discipline would overwhelm an Indian force. What they met instead was a disciplined Travancore army that cut off supplies, struck with precision, and forced the Dutch into an unconditional surrender. The scene of Admiral Eustachius De Lannoy offering his sword to Marthanda Varma stands as one of the most symbolic moments in Indian history: a European commander bowing to an Indian king. Far from killing him, Varma made him his general and used his expertise to modernize his forces. It was pragmatism at its best, combining local strength with acquired knowledge.

But Marthanda Varma’s achievements were not limited to the battlefield. He reorganized land administration, introduced state monopolies on pepper and other spices, and broke the European chokehold on trade. This economic vision gave Travancore financial muscle and stability. He also patronized the arts and literature, making Thiruvananthapuram a vibrant cultural centre. His reign produced poets like Kunchan Nambiar and Ramapurathu Warrier, and the grandeur of the Padmanabhaswamy Temple as we know it today owes much to his vision. In 1750, he went a step further and dedicated his entire kingdom to Lord Padmanabha. From then on, he ruled not as a sovereign but as Padmanabha Dasa, the servant of the deity. This act removed dynastic claims and vested sovereignty in faith, creating a unique political order rooted in devotion but functioning with pragmatism. It brought legitimacy, unity, and continuity that outlived him and strengthened Travancore for decades to come. In such a sense, a line aptly captures Varma’s achievement best: “The Indian king who threatened to invade Europe.”

RECLAIMING LEADERS FOR CONTEMPORARY INDIA

Why is all this important today? Because history is not just about the past; it is about how we imagine ourselves as a people. India is a federal and diverse nation where language, caste, and region often divide political discourse. Yet, how can we expect to bridge these divides if we do not know one another’s histories? A student in Delhi may never hear of Marthanda Varma; someone in Tamil Nadu may know little of Lachit Borphukan in Assam; someone in Rajasthan may not be taught about Rani Abbakka, who fought the Portuguese. Without this knowledge, India remains fragmented in its memory, unable to build a cohesive narrative of pride.

This is why the inclusion of figures like Marthanda Varma in our curriculum is vital. It is not only about correcting academic distortions but about fostering a deeper unity. When children learn that rulers from different corners of India stood up against foreign powers, built strong states, and preserved culture, they develop a sense of shared strength. It is through such integrated knowledge systems that we can build the confidence needed for Viksit Bharat.

Moreover, Marthanda Varma’s story is not just about resistance but also about vision. He showed that India’s rulers could defeat Europeans long before the British consolidated power. He demonstrated that strong administration, economic foresight, and cultural patronage could go hand in hand. And, like Shivaji on the western coast, he built a naval and military capacity rooted in indigenous traditions. These are lessons India must reclaim, not just to balance textbooks but to remind ourselves that our ancestors were not merely victims but victors.

Marthanda Varma’s life teaches us that resistance to colonialism began long before 1857, that regional kings could outthink and outfight Europeans, and that India’s knowledge systems were capable of producing rulers of vision and strength.

If India is to march towards Viksit Bharat, it must do so with the confidence of a people who know their past in full, not a past curated to glorify invaders but one that celebrates those who built, fought, and endured. Rediscovering Marthanda Varma is therefore not just an academic exercise but a national necessity.

Prof Santishree Dhulipudi Pandit is the Vice Chancellor of JNU.