China’s $8.5 billion Pakistan package raises questions over delivery and intent.

China’s $8.5 billion CPEC 2.0 package for Pakistan combines MoUs and project pledges, reflecting cautious investment amid delays, security concerns, and economic challenges.

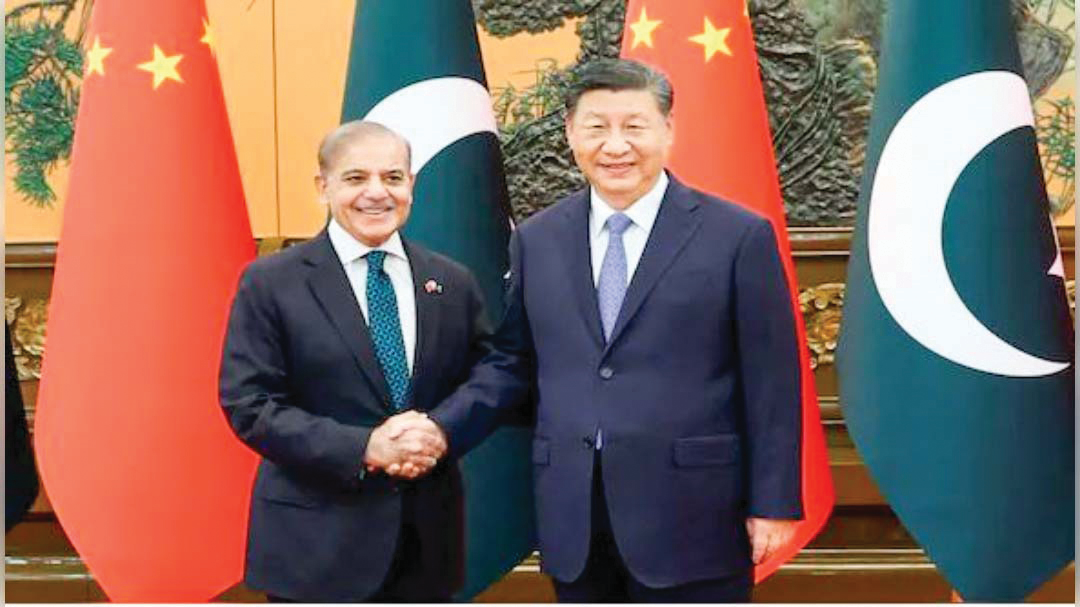

New Delhi: While Pakistan’s media, lawmakers and ministers hailed Beijing’s $8.5 billion package announced in the first week of September as proof that the China Pakistan “iron brotherhood” remains intact, regional observers say the sum and the accompanying Five-Year Action Plan (2025–2029) amount more to a calibrated set of pledges and MoUs than the kind of unconditional, economy-reordering investment once projected.

Islamabad presented the package as the core of a “CPEC 2.0,” describing cooperation across infra structure, energy, industrial zones, digital economy, climate, education and even space technology. Domestic officials emphasised headline projects such as an upgraded ML-1 rail corridor, Khunjerab Pass works and further development at Gwadar.

But observers with access to details said that the $8.5 billion reported in Pakistani statements is largely composed of memoranda of understanding, project commitments and joint venture pledges — roughly split in public reporting into headline MoUs and a smaller tranche of firm joint-venture financing — rather than a single, immediate cash transfer that would suddenly alter Pakistan’s balance sheet.

That distinction, analysts told The Sunday Guardian, matters for any assessment of what Beijing has actually put on the table and how quickly projects will move from paper to construction. The 2025–29 plan sits atop more than a decade of China’s public and private pledges to Pakistan under CPEC and the broader Belt and Road Initiative. Early project tallies and government statements listed CPEC’s potential scope in the tens of billions — much of which still remains in pipe lines and under “envisioned project value.”

When measured by realised outbound direct investment and years of disbursed project finance, the cumulative, actual flows look substantially smaller than the headline aggregates, sources noted.

China’s formal stock of direct investment in Pakistan remains modest relative to the oft-quoted CPEC valuations, and annual outbound investment flows into Pakistan in recent years have been measured in the low hundreds of millions of dollars rather than billions. “In short, promised project scope has not translated into continuous, large-scale investment that would re wire Pakistan’s productive economy,” an official who tracks the trade figures for an international agency said. A senior official with an international funding agency told The Sunday Guardian that implementation problems help explain the gap between promise and delivery.

“Flagship projects have been repeatedly delayed, repriced, re-scoped or stalled. The ML-1 railway — long billed as a transformative backbone project — was repeatedly renegotiated and its cost estimates revised in public reporting (estimates shifted from near $9–10 billion toward a smaller financing package as plans were adjusted), illustrating the difficulty of converting planning into fast execution in a country like Pakistan,” she noted.

Quoting conversations with Chinese analysts, she said they privately acknowledge growing concern in Beijing that repeated delays, mounting security costs and Pakistan’s fiscal weaknesses risk turning promised projects into what one described as a “strategic sinkhole.” The analysts stressed that while China will not abandon CPEC, the pattern of limited returns has already led Beijing to slow disbursements, rely on MoUs and demand stricter guarantees before moving ahead.

The ML-1, or Main Line-1, is Pakistan’s most important railway corridor. It stretches about 1,872 kilometres from Karachi and Port Qasim on the Arabian Sea through Hyderabad, Lahore, Rawalpindi and Peshawar up to the Torkham border with Afghanistan. It carries the bulk of Pakistan Railways’ freight and passenger traffic.

Under CPEC, ML-1 was designated the flagship infra structure project, with plans to double-track and electrify the line, modernise signalling and raise speeds for passenger trains to around 160 km/h. Original cost estimates hovered near $9–10 billion, though subsequent revisions trimmed the scale. However, its repeated delays have become shorthand for the gap between CPEC’s promises and delivery.

Similarly, Gwadar’s port, touted as a future regional transshipment hub, has underperformed commercial expectations: ship calls, cargo throughput and the cluster of industrial activity originally envisioned have remained below the levels that would justify the earlier ambitions, Indian officials monitoring the project noted. Energy sector investments have produced power capacity, but circular debt, tariff shortfalls and off-taker risk have frequently reduced the projects’ fiscal and commercial viability. Security risks — including several deadly attacks on Chinese personnel — have raised the operational cost of projects and forced Beijing to press Islamabad for enhanced protection measures and guarantees.

Analysts say such recurring security burdens erode project economics. Islamabad’s frequent attempt to link these attacks to India has not drawn the support it expected from Beijing, given the lack of concrete evidence. That gap in sympathy, observers add, helps explain why Islamabad has turned to Washington, dangling rare earths and oil as incentives for the Trump administration.

“When Beijing isn’t as accommodating on issues of security, financing and political cover, Islamabad dangles strategic carrots to Washington to regain leverage. It is not something new and is a standard practise that they seem to have mastered,” the official quoted above said. Taken together, these operational frictions — delayed delivery, fiscal strain, security overhead and administrative bottlenecks — have materially reduced the rate of return and strategic payoff Beijing might have hoped to extract, observers in Delhi said.

The economic pattern of the relationship has been instructive. Bilateral trade has grown and China is now Pakistan’s largest trading partner by volume, but the balance has been heavily tilted in China’s favour, trade analysts pointed out. Pakistan’s exports to China remain limited in value and technological complexity while Chinese manufactured goods and equipment have flooded Pakistani markets.

That trade profile increases commercial ties but does not equate to the technology transfer, industrial upgrading or export-led growth for Pakistan that would have delivered reciprocal, large-scale returns to China in the form of new, resilient export corridors or trusted manufacturing bases.

Where Beijing sought integrated industrial zones and export hubs powered by Chinese capital and technology, the reality has been a slower, more limited pattern of project-by-project investment and a concentration of Chinese commercial benefits rather than the widespread industrial transformation once promised, a security analyst based in Delhi noted. Pakistan’s macroeconomic fragility compounds the problem. Recurrent balance-of-payments crises have forced Islamabad to stitch together support from multiple sources — IMF stabilisation programmes, roll overs and deposits from Gulf partners, ad hoc rescheduling by bilateral creditors and occasional Chinese financing or short-term support.

Despite large headline pledges under CPEC, Pakistan continues to rely on traditional external buffers. That reliance undercuts the narrative that China has become a single, unconditional financial backstop, officials based in Dubai, who monitor the developments, told The Sunday Guardian.

Washington has remained a consistent element in Pakistan’s strategic and financial orchestra. Over decades the United States has provided military assistance, training, security cooperation, development aid and emergency support. In the post 2001 era, those military-to military channels revived, both openly in equipment sustainment and quietly in counter-terrorism coordination — something which has not gone unnoticed in Beijing.

Islamabad’s repeated outreach to Washington — seeking political space, financial backing or diplomatic cover — is part of a long-standing pattern in which Pakistan alternates and layers patrons to manage vulnerability. China’s role has therefore always been only one element in a broader portfolio of external relationships that Islamabad leverages.

That pattern — Pakistan asking for more, other partners periodically stepping in, and Beijing absorbing the political and security costs of projects — has shaped Chinese strategic thinking. For many in Beijing, Pakistan remains useful in tactical terms: a geographic outlet to the Arabian Sea through Gwadar, a partner that complicates Indian calculations, and a theatre in which China can project influence on Pakistan’s western flank. But those tactical returns have limits.

“The ceiling is evident in the mismatch between the headline financial valuations and the sum of durable economic payoffs: limited market scale, low absorptive capacity, a persistent fiscal drag and elevated implementation risk,” a former diplomat, whose last posting was in a South Asian country, said.

By contrast, India presents a different calculus for China — a far larger market, a more diversified manufacturing base, and potentially more economically rewarding supply-chain integration if political barriers could be eased.

That comparative assessment lies at the heart of Beijing’s recent diplomatic posture: rather than treating Pakistan and India as an indivisible package, Chinese policy has tilted toward “de-hyphenation,” managing each relationship on its own terms.

“We are witnessing some level of de-hyphenation. Beijing is keeping Pakistan within a managed strategic orbit and selectively advancing projects that secure logistics and access, while simultaneously testing avenues with New Delhi as this could yield much larger, long-term economic returns for China. Diplomatic signals in 2024–2025 — quiet contacts, restrained rhetoric and careful economic outreach — illustrate Beijing’s interest in preserving room to manoeuvre toward New Delhi without severing ties to Islamabad,” the official quoted above observed.

That shift in tone and tactic is practical: it allows Beijing to avoid letting commitments to Pakistan become an anchor that excludes a larger strategic prize.

For Islamabad, the announcement delivers immediate political and rhetorical value, and it sustains priority lines of cooperation that keep projects moving.

“If the empirical question is whether CPEC and BRI have produced the returns Beijing originally envisioned from Pakistan, the evidence points to an outcome short of that benchmark,” the official with the international funding agency said.

The correct characterisation, she said, is mixed: CPEC/BRI generated strategic and infrastructural assets for China, but they have not — on available evidence — translated into the comprehensive economic transformation or reciprocal industrial upgrading in Pakistan that once animated Chinese ambitions.

That mixed result helps ex plain why Pakistan continues to pursue a multipolar external policy, repeatedly reaching out to Washington, Riyadh and other capitals even as it courts Beijing, and why Beijing now calibrates its ambitions: sustain what is useful, demand clearer implementation and keep the door open for higher-value engagement elsewhere, observers in Delhi said.