The unprecedented, undiplomatic assault by one founder member on another fellow member doesn’t augur well for G-20. Unlike UNSC, in G-20, no one has a veto power.

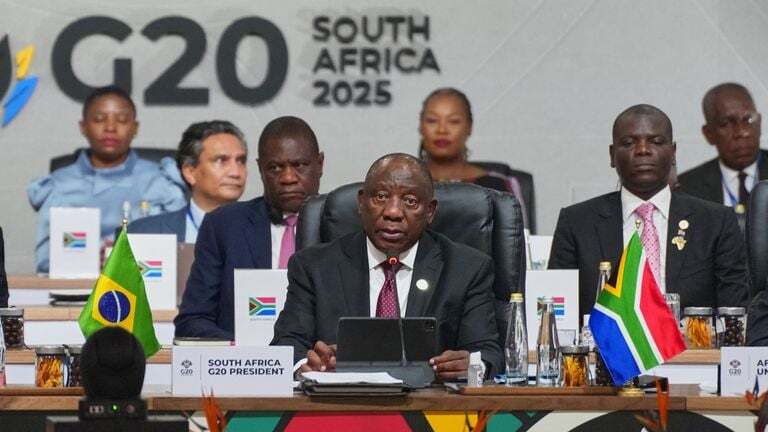

G20 Johannesburg summit ends in consensus but faces turbulence after sharp US criticism of South Africa’s presidency (Photo: File)

NEW DELHI: Born in 1999 in the aftermath of Asian financial crises of 1997-98 to address economic and financial stability in the world, initially comprising the finance ministers and governors of central banks but subsequently raised to the level of the head of state or government by the US in 2009 following the financial crises of 2007-2008, presently accounting for 85% of global GDP, 75% of global trade and 2/3 of the world population, G-20 has covered a long distance. The idea behind its foundation was the realization that major global crisis can’t be solved by the developed countries alone without co-opting emerging economies. Presently, its membership includes 19 countries: G-7 and countries from Asia, Africa, Latin America and the Middle East, selected probably by the size of the GDP, EU and AU admitted at G-20 2023 Summit in Delhi. It’s the only organisation of its kind which brings the developed and developing countries on the same platform and runs without a permanent secretariat; its presidency rotates and the Troika: the past, the present and the incoming president maintain continuity; its decisions are taken on the basis of consensus.

As the presidency rotates and there is no veto power vested in any member, it provides a degree of prominence, visibility and opportunity to the current president to steer the discourse and flag issues which are relevant to it and its region. Over the years, its agenda has expanded and included trade, climate change, sustainable development, energy, environment, agriculture, health, terrorism, corruption, women empowerment, and raging international conflicts like Ukraine and Gaza, besides the original financial economic issues. While this phenomenon provides an opportunity to draw attention to global commons and discuss issues which impact many countries and regions, it also introduces potential for disagreements and controversies which makes it much more difficult to reach a consensus.

The first ever G-20 Summit in Africa, the fourth by a developing country after Indonesia, India and Brazil was held in Johannesburg on November 22-23 and has managed the Leaders’ Declaration by consensus in spite of its boycott by the US and absence of the Presidents of Russia, China, Argentina, Mexico and Indonesia. The Declaration flagged climate and energy transition, underlining the need of tripling renewable energy capacity by 2030, doubling energy efficiency and mobilising higher public and private funds for energy transition; developing countries need US$ 5.8-5.9 trillion before 2030 for meeting climate finance and climate resilience. Declaration asks for the provision of electricity for 300 million Africans. Keeping in mind indebtedness in Africa, the declaration stresses debt reforms and access to affordable and sustainable finance. The Summit acknowledged Africa’s role in extraction, value addition and promotion of rare earth and critical minerals supporting green industrialisation and manufacturing partnerships.

South Africa introduced the Ubuntu Initiative inspired by “I am because we are” philosophy, which aims global cooperation through an African lens. It reaffirms right to food and supports African farmers and wants AI and Digital Inclusion in Africa. The Declaration also demands the reforms of the UN Security Council to make it more representative and reflect today’s realities rather than remain mired in the world of 1945.

PM Modi’s six proposals: Africa Skill multiplier programme which proposes to train 1 million African trainers in the next 10 years, establishment of a Global Traditional Knowledge Repository, Global Healthcare Response Team, Creation of the Critical Minerals Circulatory Initiative, Initiative to Counter Drug-Terror Nexus and Open Satellite Data Partnership were received positively as was his exhortation for greater collective action to combat climate change and strengthening food security.

But the Summit’s much publicised claims were dismissed by a frontal attack by the US President on the South African President Cyril Ramaphosa for prosecuting White Afrikaners violently (in the Oval Office last month, in Ramaphosa’s presence, he had called it a genocide) and not handing over the gavel of the Summit to the officer of the American embassy at the closing session and weaponizing its presidency by passing the Leaders’ Declaration without USA’s participation. He went on to declare that South Africa wasn’t fit to be a member of any organisation and he would not invite South Africa to the Next G-20 Summit in Florida next year. Adding salt to injury, he added that he was stopping all payments and subsidies to South Africa and reiterating tariffs of 30% on South African exports.

This unprecedented, undiplomatic assault by one founder member on another fellow member doesn’t augur well for G-20. Unlike UNSC, in G-20, no one has a veto power irrespective of the size of one’s economy nor has anyone been vested with the authority to expel any member. But if he sticks to what he has said and doesn’t invite Ramaphosa, what can other members do? Plead with him to reconsider his decision and extend an invitation to South Africa? He might demur but insist that Ramaphosa take strict action against officers who might have been guilty of high-handed action against White Afrikaners? It’s shadow boxing. Basically, he is doing this as a retaliation to South African accusations in ICJ against Israel of committing genocide in Gaza.

If he doesn’t backtrack, some members might threaten not to attend the Florida Summit or send very low-level representatives. But G-7 members will not abstain. Saudi Arabia, South Korea and Turkey are unlikely to go against Trump. A lot will depend on what stand China takes. Brazil is most likely to stand by South Africa. And it will put India in a difficult spot; still struggling to sign the BTA with the US and trying to get the 25% punitive tariff for importing Russian oil lifted, it will be least inclined to annoy Trump at this juncture. But keeping in mind India’s historic relations with South Africa and having stressed the ideal of Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam and pursued the theme of One Earth One Family and One Future, India should come to South Africa’s defence. The whole idea of disallowing a member to attend a Summit is undemocratic and runs counter to the spirit of G-20.

But having withdrawn from the Paris Climate Agreement and WHO and having little love lost for the WTO, after trashing BRICS and putting Quad in a limbo, pushing the G-20 into a battle zone of developed vs developing countries, unless it sings to his tunes, shouldn’t be a big deal for DJT.

Surendra Kumar is a retired ambassador of India.