Perhaps the most troubling consequence lies in what such a trajectory would mean for the Arctic itself. The Arctic is not merely another contested space; it is a planetary regulator of extraordinary importance.

New Delhi: When Donald Trump recently revived the idea of Greenland as a strategic necessity— this time articulated from Iceland—the argument drew upon a deeply ingrained geopolitical instinct: that control of territory still equates to security. Location, leverage and possession were once again presented as reassurance in an unstable world. Maps, it appeared, were expected to do the strategic heavy lifting.

This reasoning echoes Robert Kaplan’s influential thesis in “The Revenge of Geography”—that physical terrain and spatial constraints ultimately reassert themselves over ideology and ambition. Kaplan’s caution against ignoring geography remains relevant. Yet the renewed fixation on Greenland reveals a more contemporary strategic error—not the neglect of geography, but its misapplication. In an era shaped by hypersonic weapons, compressed decision cycles, cognitive warfare and accelerating climate stress, geography alone no longer delivers the security outcomes policymakers assume.

The Greenland debate thus exposes a deeper tension be tween inherited territorial reflexes and the realities of 21st century conflict. It reflects an impulse to seek safety in possession at a moment when power is increasingly determined not by what states occupy, but by how effectively they anticipate disruption, absorb shocks, and shape perception across domains.

Much of the discourse assumes that tighter control over Greenland would automatically enhance the United States homeland security. This assumption deserves closer scrutiny. It is rooted in a 20th century understanding of strategic depth—shaped by predictable ballistic trajectories, fixed early-warning systems and relatively stable escalation dynamics. During the Cold War, forward geography bought time and reassurance. Today, that logic is increasingly misaligned with the character of conflict.

We now operate in an era defined by hypersonic and hypervelocity weapons, manoeuvrable trajectories and severely compressed decision cycles. Threats emerge across domains—space, cyber, undersea and informational—often simultaneously and with minimal warning. In such an environment, fixed geography offers far less protection than it once did. Forward locations and territorial buffers that once provided strategic comfort now yield only marginal advantage against multidirectional threats. Security today flows less from possession of territory and more from resilience: dispersion of assets, redundancy of systems, technological adaptability and—critically—cognitive preparedness. Over-investment in geography risks strategic distraction, drawing attention to static spaces while adversaries exploit non-geographic seams of vulnerability, such as data networks, supply chains and societal cohesion.

This raises an unThis raises an uncomfortable question. Does coercive acquisition or control of Greenland meaningfully improve security, or does it create new vulnerabilities— political, legal and strategic? Geography still matters, but it no longer guarantees insulation. When treated as a substitute for adaptability, it can even become a liability.

Beyond strategic efficacy lies a more fundamental concern: legality and legitimacy. Any coercive move against Greenland would strike at the heart of the international legal order. It would violate the core principles of sovereignty and territorial integrity enshrined in the UN Charter. The prohibition on the threat or use of force against the political independence of states is not a procedural norm; it is the foundation of post-1945 stability. Undermining it weakens the very architecture that prevents power from sliding into arbitrariness.

Even in the absence of open hostilities, coercive territorial assertions blur the line between peace and conflict. They normalise grey-zone behaviour, lower thresholds for escalation and accelerate militarisation. History suggests that such actions rarely remain isolated; they generate precedents that others are quick to exploit.

The repercussions would extend well beyond the Arctic. In Europe, any move perceived as coercive would place severe strain on the unity of the European Union and NATO. Greenland is inseparable from Denmark, a NATO ally. A challenge to its status would test alliance cohesion, credibility and political resolve at a time when unity is already under pressure. Rather than strengthening Western security, such actions could expose fissures and complicate collective decision-making. For NATO, the implications would be particularly stark. The alliance rests not only on shared threats but on shared values. If principles such as sovereignty and consent are applied selectively, NATO risks hollowing out its moral centre—undermining the trust of smaller members whose security depends more on norms than on raw power.

Russia and China would draw their own conclusions. Moscow would view any shift in Arctic norms through a hard-security lens, accelerating its own militarisation of the region. China’s official response to the Greenland debate has emphasised respect for territorial integrity while projecting itself as a “near-Arctic state” engaged in scientific cooperation and climate research. Such narratives, however restrained, reflect a readiness to adapt quickly to any erosion of established norms.

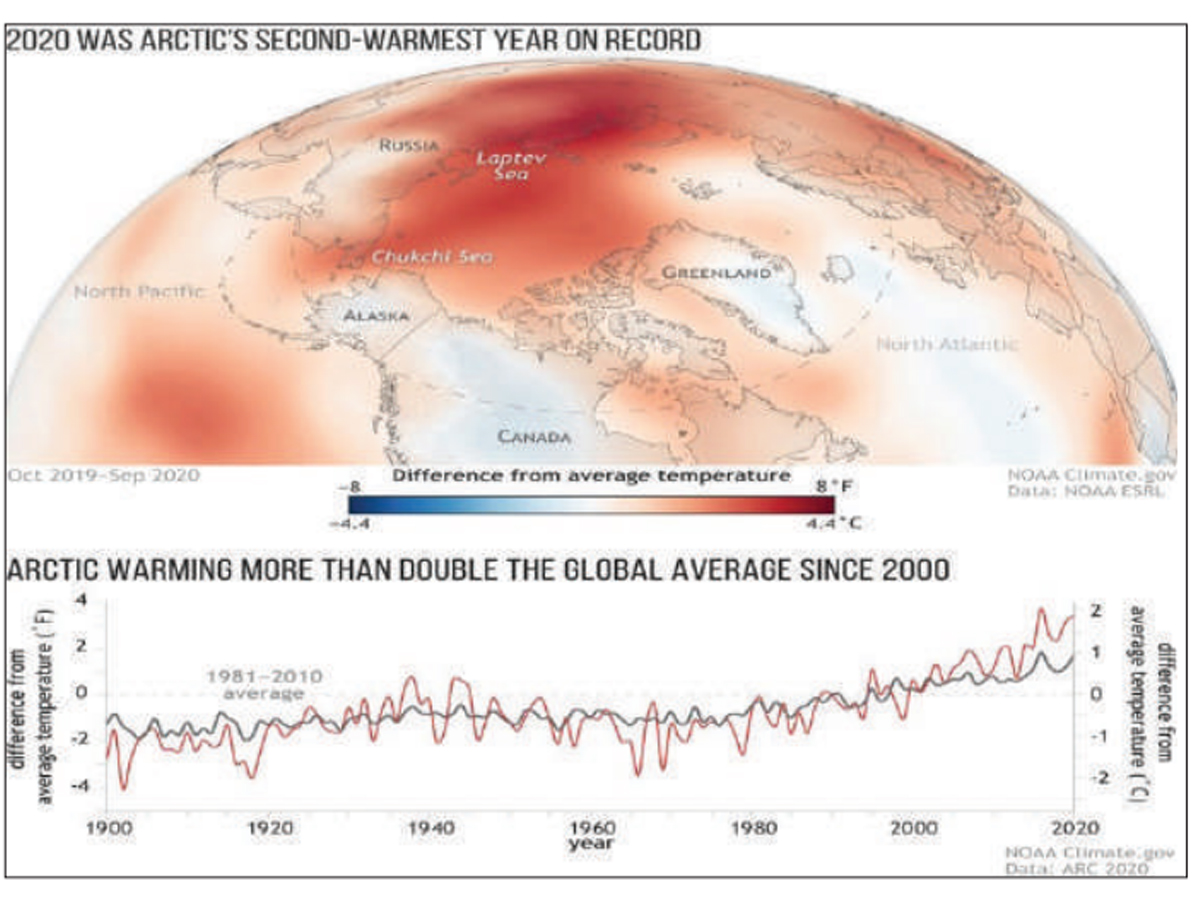

Perhaps the most troubling consequence lies in what such a trajectory would mean for the Arctic itself. The Arctic is not merely another contested space; it is a planetary regulator of extraordinary importance. Warming at nearly three times the global average, the region is undergoing rapid and potentially irreversible transformation. Accelerated ice melt threatens methane release, permafrost degradation and cascading disruptions to global climate systems—classic “grey rhino” risks that are widely recognised yet persistently under-addressed.

Militarising the Arctic under these conditions is strategically myopic. Expanded infrastructure, intensified patrols, and heightened rivalry increase the risk of miscalculation while exacerbating environmental stress in an already fragile ecosystem. The security–insecurity dilemma deepens: actions framed as defensive by one actor are perceived as offensive by others, triggering dynamics that the region—and the planet—can ill afford.

For decades, the Arctic has been governed—unevenly but deliberately—through cooperation, restraint and scientific collaboration. Institutions such as the Arctic Council were designed to prevent zero-sum competition from overwhelming shared interests. Undermining this framework would signal a broader retreat from multilateralism at a time when global governance is already under strain.

What, then, are the lessons for India?

India’s strategic experience offers a sobering counterpoint to territorial romanticism. From Siachen—the world’s highest battlefield— to the enduring consequences of the Shaksgam Valley, ceded by Pakistan to China, India understands both the utility and the limits of geography. Terrain can impose costs, shape behaviour and constrain options—but it cannot, by itself, guarantee security or strategic advantage.

In the 21st century, leadership lies less in controlling ice or rock than in managing fragility—environmental, technological, normative and cognitive. Geography still matters, but only when integrated with resilience, legitimacy and adaptability. Treated in isolation, it becomes a false compass— comforting, familiar, and strategically misleading.

Viewed through this lens, Greenland is not a strategic prize to be seized but a test of strategic maturity. In an age measured in milliseconds, perception cycles and methane thresholds, the true measure of power may lie not in what states can dominate—but in what they have the foresight to govern, the restraint to preserve, and the wisdom to leave undisturbed.

* Maj Gen B.K. Sharma (Retd) is a strategic analyst and former Director General, United Service Institution of India.