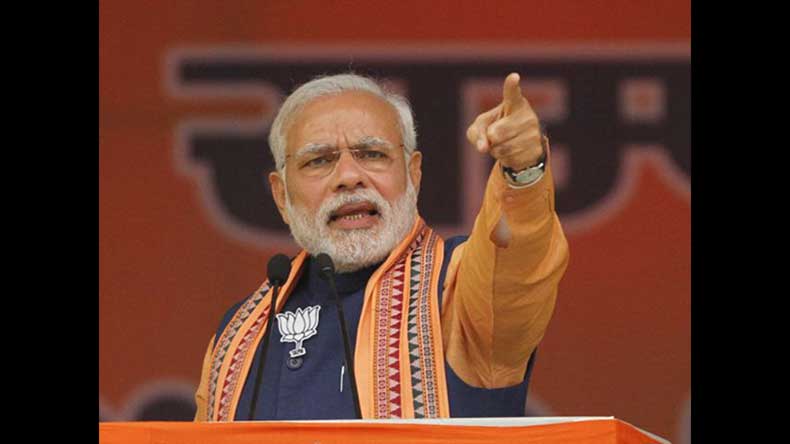

Officials in sync with the objectives of Prime Minister Narendra Damodardas Modi claim that there is global appreciation for his “braving personal unpopularity and the risk of low future seat tallies for the BJP” so as to implement a scheme that he has “had in mind since 26 May 2014”, his first day in office. Given his “methodical mindset”, the substantial and uncontrolled role of the informal economy has occupied much of Modi’s time. Not only does the government not control this vast sector, “it does not even have any idea about its extent and activities”. To the Prime Minister, “such an unregulated sector is akin to the ‘Dark Net’, the shadowy world of the deep internet that is resistant to policing”, an official said. The officials say that from Day One, the Prime Minister has been determined to ensure that all transactions in the economy get recorded, “both for revenue purposes as well as to ensure that anti-national elements do not misuse their access in order to create trouble for citizens”. They point to the Jan Dhan Yojna, PAHAL and MUDRA schemes as being “part of a continuum of activities leading up (to the 8 November currency swap)”. The Prime Minister’s vision is to see “every adult citizen of India have a bank account and access the internet in the palm of his hand”, and he has “worked on a plan to ensure both before 2020”. Early on, PM Modi tasked officials with “working out ways to ensure 100% access to banking and conversion of the informal economy into the formal space”, but by May 2016 as he entered the third year of his term, the Prime Minister was “feeling impatient at the slow progress made and decided to quicken the pace by leading from the front”. Two officials, who were in “complete harmony with the Prime Minister’s desire for speed, were Principal Secretary to the Prime Minister, Nripendra Mishra and National Security Advisor Ajit Doval”. According to the officials spoken to, “both were enthusiastic advocates of the currency swap scheme in internal meetings”, albeit for different reasons. From the outside, finance guru S. Gurumurthy played an “important role in selling the idea (of a lightning currency swap) to the top”. The official reiterated that “none of the bankers consulted expressed any apprehensions about the scheme” and that the RBI leadership was “totally in support of the move, as was the Economic Advisor to the Finance Minister and other officials of the Ministry of Finance”.

A characteristic of the Second Generation NDA Government has been that those from the outside with dissenting or out-of-the-box views have been excluded from participation in the policy process. Official advisory bodies have been few and those created have been both truncated and filled with retirees from service who may be expected to faithfully echo the line taken by the government. According to an official, the Prime Minister is under severe pressure of time and hence unable to meet with as many people outside the bureaucracy as was the case when he was Gujarat Chief Minister. Access to PM Modi is much more difficult (and in most cases impossible) than was access to CM Modi. While a flood of suggestions comes in via the internet, “almost all of this gets dealt with at the junior officer level”, and often these “lack the judgement needed to decide which should get referred to higher ups and even the Prime Minister”. Modi has always shown a willingness to accept new ideas and listen to different voices, that is, provided these gain access to him. “While he lasted, P.N. Haksar as Principal Secretary to Indira Gandhi used to ensure that the PM met at least two or three individuals of strong and contrary views each week. The same needs to take place now”, a former high official said, adding that “the way the currency swap is being implemented in practice shows the weaknesses of our inbred bureaucratic system that listens only to echoes of its own voice from the outside and dismisses the rest as inconsequential or motivated.”

The colonial bureaucracy’s focus on a single objective to the detriment of the overall benefit is illustrated in the continued refusal of the authorities to permit the (free from direct taxes) farm sector to use extinguished currency notes for sale and input purchase. The loss of farm output through wastage and for other reasons as a consequence of the severe liquidity shortage the farm sector has been experiencing since 8 November, is far more than any gain consequent to lesser tax

That several at the apex of the banking pyramid in this country have very limited knowledge of ground reality seems clear from bank officials’ remarks such as “the line outside branches and ATMs is coming down”. This is not because of lack of demand for currency, but a lack of cash in ATMs and in bank branches. Those where there is some cash to dispense are seeing long queues. As for the rural areas, currency supply has been much lower than in the cities, despite the political importance of the rural vote. In UP, Uttarakhand, Punjab and Gujarat, the way in which the currency swap scheme is being implemented is likely to impact voting behaviour substantially. The transport industry is down with trucks idle, while retail business has fallen across the country. Latest by the close of 50 days beginning 8 November 2016, access to cash needs to get restored to pre-8 November levels for the economy to right itself. Any further delay would result in an unimaginable situation very different from that anticipated by Prime Minister Modi when he signed off on the suggestion from some officials that he approve the shock withdrawal of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes. The “reason for the Rs 2,000 notes was to speed up the volume of money supply as these get printed at the same rate as the Rs 100 or Rs 500 notes”, an official claimed, adding that “the level of safety features is the same as in the older versions”.

The total currency in circulation on 30 September was Rs 17 lakh crore, of which 500 and 1,000 rupee notes amounted to 15 lakh crore rupees in value. The Rs 100 notes were 12% in value, the Rs 500 notes 46% and the Rs 1,000 notes 40%. A total of 21 billion notes of 500 and 1,000 were in existence. In the four currency printing presses, only 3 billion notes of all denominations can get printed in a month. Of this, the 6 billion Rs 1,000 notes will get cut down to 3 billion Rs 2,000 notes. Printing Rs 100 notes takes the same time as printing a Rs 2,000 note, and there is a looming shortage of these, as demand has spiked since 8 November. Apart from printing, the average time taken for dispensing to consumers is 36 days, according to an official. The math will show the speed at which the currency shortage can get addressed in a meaningful way. About six months is the minimum, which is why those saying that currency supplies are adequate need to explain their remarks.

The coming week will be a crucial period for the bold scheme announced by Prime Minister Modi. Unless the ground situation improves substantially, economic distress will be unmanageable.

Those whom the Prime Minister has trusted with handling the machinery of government will need to deliver on their promises to him, so that he himself can keep the promise he has made to the people of India, of witnessing a smoothly running and corruption free economy within 50 days of this unprecedented decision. Modi’s bold move will enter the Guinness Book of Records for a single decision affecting the maximum number of people (1. 26 billion) in the shortest possible time (less than four hours). Those who are well-wishers of Prime Minister Modi hope that the team personally chosen and assembled by him will deliver the results expected of a government led by a maestro of the calibre of Narendra Modi.