SHANGHAI: On 28 August, India and China agreed to roll back their 10-week long military standoff at the tri-junction with Bhutan. The road to “re-normalisation” of relations will be tedious. Doklam crisis exposed the deep-seated mistrust, and mutually harboured negative feelings among sections of the public and elite—especially the media. The Chinese press has been particularly churlish, and dismissive of Indian capabilities and resolve. Given the media’s direct relationship with the state, many Indians took the harsh rhetoric to represent official views. This contrasted with the Indian government’s gravitas and its resistance to growing calls for suspension of talks. Chinese elites, for their part, are stung by what they perceive to be India’s repeated slights, and obstructionism in the full glare of world attention, be it the rejection of Belt Road Initiative, or halting of road-construction activities in border areas. There is no love lost, and it is difficult, under the circumstances, to make the case for engagement.

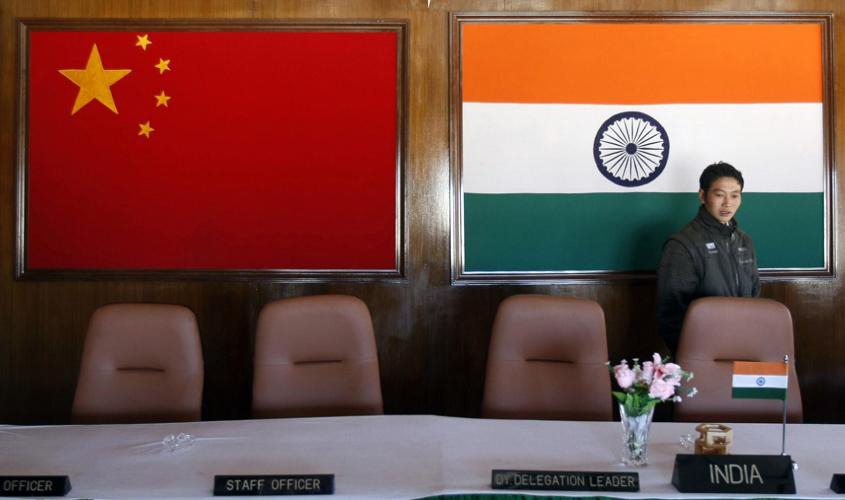

SHANGHAI: On 28 August, India and China agreed to roll back their 10-week long military standoff at the tri-junction with Bhutan. The road to “re-normalisation” of relations will be tedious. Doklam crisis exposed the deep-seated mistrust, and mutually harboured negative feelings among sections of the public and elite—especially the media. The Chinese press has been particularly churlish, and dismissive of Indian capabilities and resolve. Given the media’s direct relationship with the state, many Indians took the harsh rhetoric to represent official views. This contrasted with the Indian government’s gravitas and its resistance to growing calls for suspension of talks. Chinese elites, for their part, are stung by what they perceive to be India’s repeated slights, and obstructionism in the full glare of world attention, be it the rejection of Belt Road Initiative, or halting of road-construction activities in border areas. There is no love lost, and it is difficult, under the circumstances, to make the case for engagement.And yet, there is no option but to engage. It is imperative that we stay on track so as not to derail 30 years of confidence building measures; joint working groups; multi-sectoral cooperation; people to people contact; and multilateral institutionalisation. The Doklam crisis, which pitted two nuclear-armed neighbours face to face, is the strongest argument for continued engagement, rather than for downgrading of relations. The standoff did not escalate to the point of use of firepower, and was resolved after several rounds of discussion and dialogue. Speaking for the Indian side, not only does this honour the professionalism and preparedness of the Indian armed forces, by saving their strength for “last-resort” situations, but this also validates the diplomatic mechanisms already in place. The Chinese side has, correspondingly, stayed the course.

The timing of the stand-down in Doklam is being interpreted by Indian analysts as China’s calculated move to shift the spotlight to Xiamen BRICS Summit; and eventually to the all-important 19th Chinese Communist Party Congress. This is entirely plausible. I venture to add that years of engagement have fine-tuned the Indian government to the subtleties of the “Chinese Way”. Government of India is aware that despite the good cop-bad cop routine, the Government of PRC, its media and its public are not a monolith, and that a responsible major power (as India aspires to be) must tease out all available avenues for engagement. As an Indian living and teaching in China for a decade now, I have had the opportunity to observe the Indian mission in Beijing, and especially in Shanghai. Although the mission is small, relative to China’s strategic importance, it is both impactful and focused. In just under a decade, I have witnessed among Chinese netizens a growing interest and curiosity toward Indian culture and society. Likewise, the Indian community in China is small in numbers, but strong in impact. The Indian business community especially, has built upon the momentum in growing bilateral ties and has ventured to the farthest corners of mainland China seeking trade and investment opportunities.

While the attention has, quite justifiably, been on India’s unfavourable terms of trade, Brand India has several untold success stories to tell. For instance, in an environment where joint ventures (JV) are the norm, the first wholly-owned foreign enterprise (WOFE) in China is an Indian IT education and training company. There is, likewise, a growing demand for Indian cultural products, with yoga and “Bollywood” having captured the imagination of the entire Chinese nation. We have barely scratched the surface of the business, education and cultural possibilities that exist for altering the balance of trade.

Admittedly, the disputed India-China border is long, and the trade gap, wide. However, there are far greater issues that confront us: climate change, public health, food and water security, humanitarian disaster relief, job-creation, terrorism and crime prevention… These are global challenges that require coordinated solutions, possible only if China and India work together. The statistics, though familiar, are still staggering—2.5 billion combined population; shared waterways that sustain all of Asia; millions of “missing girl children” in both countries and the social consequences thereof; a projected youth bulge in India, and an ageing population in China.

As aspiring powers, China and India must continue to refine and readjust their terms of engagement. The hallmark of being a great power is the ability to understand, analyse, and possibly influence situations in a wide geographical area outside of your own. This is not a sinister proposition, but a practical one. From lobbying for mundane issues such as work permits for one’s citizens, or prime slots at airports for one’s national carrier, to weightier goals such as country-specific industrial parks, or speeding up approvals for drugs, what is needed is textured engagement. India has developed this sort of engagement in the Middle East and North America, through government channels, businesses, individuals and NGOs. Such a high quality of engagement is necessary and inevitable if India and China are to grow mutual interests, and to solve common challenges.

Despite 2,500 years of cultural/economic contact by way of Buddhism, ancient silk roads, and present-day SED (strategic and economic dialogue), two of the world’s oldest and attractive civilisations are stuck with unattractive trade deficit and trust deficit. The irony is that there are complementarities in the two economies that we are yet to fully leverage. The Indian side is short of capital goods and infrastructural inputs, for which local production is yet distant, and Western imports too expensive. On the Chinese side, India continues to offer a safe and legally well protected environment for investment, a skilled, dependable workforce, and advances in pharma and services industry that could help solve China’s social challenges. At the international level, China wields clout, given its huge trade surplus and ability to “get things done”. India shows complementary strengths—a strong legal system, goodwill, ability to work in a chaotic environment, under the “constraints” of a democracy, while not being perceived as a threat. The two could well work together to bid for projects in third countries. This seems to be wild optimism, but in fact, there is precedent (MOU inked by ONGC and CNPC for co-operation in the hydrocarbon sector) for such a way forward. The question is not “why engage?”, but “how to engage?”.

Indira P. Ravindran serves on the Faculty of International Relations and Public Affairs at SISU (Shanghai International Studies University) in China.