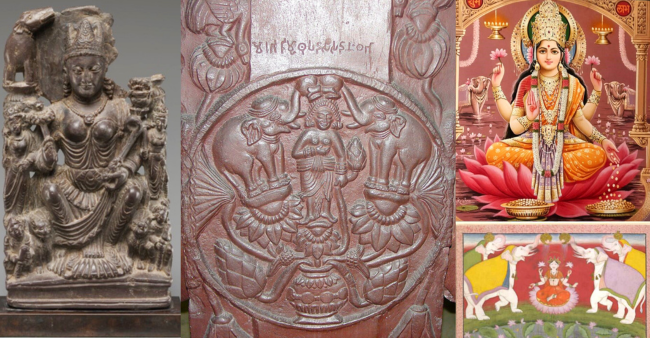

The most familiar image of Goddess Lakshmi is of the serene deity, seated or standing on a lotus, holding lotuses in her hands. Her lower hand, in the varada mudra, bestowing gold coins while she is flanked by two elephants on either side. This depiction, rooted in early iconography, was popularized by oleographs and calendar art and is especially prominent during Lakshmi Puja. As Deepawali approaches, it is time again to get ready to welcome Lakshmi into our homes. In this festive spirit, let’s explore the myriad representations of the Goddess and how they have evolved through the centuries.

The earliest mentions of the Goddess are found in Yajurveda (1200–900 BCE), wherein Sri and Lakshmi as identified as distinct deities. However, a later appendix of the Rig-Veda, introduces the hymn Sri-Sukta which identifies Sri and Lakshmi as one and the same goddess. The attributes of the Goddess mentioned in the hymn expand on her connection to fertility, childbirth, abundant harvest and her role in sustaining the natural world. Significant features of Goddess are detailed in the hymn associating her with the lotus and the elephant, which become an important part of her iconography. The lotus, with its roots in the mirky waters and rising above to bloom, signifies purity, and spiritual power, a motif prevalent in both Hindu and Buddhist art. Elephants have traditionally been connected with rains, and royal authority, and regal power. Occasionally, she is also depicted alongside an owl, her vahana or vehicle.

Early representations of Sri Lakshmi are found on coins dated to the 2nd or 1st century BCE. A prime example is the coins of Azilises, the Shaka king of Gandhara, where she appears in a standing position on the lotus and along with the elephant on either side. Such was her widespread appeal that many foreign rulers of Northern India, like Azilises, Rajuvula, and Sodasa, showcased her on their coins. And probably this was the origin of her association with material wealth.

From the 2nd century BCE, depictions of the Goddess also adorned the railings and gateways of stupas and temples. In the Bharhut stupa railing relief, she stands on a lotus blooming out of a purnaghata, or pot of plenty – another key aspect of her iconography. The goddess is adorned with kundalas in earlobes and an elaborate waistband.

By the Gupta period (circa 400 CE), Sri Lakshmi becomes consistently associated with Vishnu as his consort. Mythologically Sri Lakshmi’s association with Vishnu comes about in the context of Samudra Manthan. In addition to symbolizing prosperity and fertility, the Goddess came to epitomize power, high-rank, and glory, making her a popular figure on coins. This prominence is evident in Gupta coins, such as the one from the reign of Prakasaditya, dating back to the 5th century CE.

Lakshmi’s popularity is evident from the Pallava temples of Tamil Nadu to the Hindu architectural marvels of Kashmir. Concurrently, her iconography made its way to foreign lands in the east, reaching as far as Japan. The 10th-century architectural relief from the Banteay Srei Temple in Angkor, Cambodia, portrays the goddess in her iconic form.

While there have been variations of the iconography depending on region, local traditions, and medium of art, the distinctly identifiable symbols of Lakshmi remain largely unchanged. Mughal, Rajput and Deccani paintings see many stylisations and forms of the Goddess. This Pahari miniature possibly from Kangra, shows a variation of Lakshmi, known as Kamala, flanked by two elephants on each side, seated by a lotus pond.

In more recent history, schools of painting such as Kalighat are known for their portrayal of the Goddess in their distinct style characterised by bold watercolour strokes and shading. This depiction features Lakshmi in a Bengali sari and jewellery, mirroring the fashion of the era.

One of the notable forms of paintings from the South which has a popular representation of Lakshmi is the Tanjore school, where artworks pay meticulous attention to Lakshmi’s iconography and embellishment. This style developed as an amalgamation of Vijayanagara, Maratha and Western schools of painting.

In September 1894, the press introduced chromolithographs of Goddess Lakshmi, one of Raja Ravi Varma’s most iconic images. This rendition became immensely popular, thanks to advancements in printing technology. Various artists and publishers adopted a similar imagery, which subsequently graced advertisements, calendars, postcards, greeting cards, textile labels, and matchboxes. By mid-20th century, this vivid portrayal of Lakshmi, influenced by Western art conventions and adorned in a sari, held a special place in homes and offices nationwide.

From embodying fertility to symbolizing prosperity, the goddess’s image has evolved through the ages; however, despite many influences through time and across regions, her imagery has remained largely unchanged. Her iconography has an everlasting impression that will get carried through time and generations in future. As we light the diyas for Lakshmi Puja this Diwali, may the Goddess bless us all with abundance of peace and prosperity.

Jayesh Mathur is an architect, independent scholar, and Indian art collector & Supriya Lahoti is a museum professional and consultant with the Ministry of Culture.