Strangely, Shastri’s death remains shrouded in mystery till date. No one believes the official version, which said Shastri had died of a severe heart attack.

Every morning, two vendors ride their bicycles with coffee carriers into a park that is home to a bust of an Indian Prime Minister.

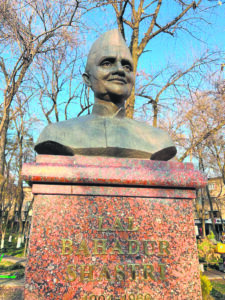

Both wait for visitors to come and buy coffee and see the bust of Lal Bahadur Shastri, India’s second Prime Minister, who died a sudden death in this city almost six decades ago. The bust is mounted on a pedestal of pink granite, brisk traffic ply on the adjacent road called Shastri Street.

But the vendors do not make great sales because very few visit the park in the heart of Tashkent. The coffee sellers return almost every day without sales. But strangely, they are back the next morning. Friday, the day for the special prayers in Tashkent, is an exception. The two coffee sellers then take a break.

“No one knows the vendors. They come without fail, week after week,” says Mazharob Dostum, a bystander.

Taxi drivers in Tashkent say they have genuine problems in reaching the park, which lies close to the Amir Timir—Taimur Lang for Indians—metro railway station. The bust of Shastri is not on the high list of tourists visiting the capital city of Uzbekistan. Shastri is not uppermost on the minds of Indians visiting Tashkent. Only those politically inclined visit the bust in the park.

“This place is visited by only a handful, mostly Indians,” claims Zikander Ajemal, a front office manager of Hilton, counted among the top hotels in Tashkent.

Interestingly, the Tashkent chapter of the Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICCR), known as Lal Bahadur Shastri Centre for Indian Cultural Centre runs a host of programmes for locals, even organising a few functions every year.

Strangely, Shastri’s death remains shrouded in mystery till date. No one believes the official version put out by the then Indian government, which said Shastri had died of a severe heart attack, his second.

Shastri had a heart attack in 1959. He was frail and sometimes needed help for movements. Once a lift was fitted near the Red Fort for Shastri to access the ramparts for the mandatory 15 August Independence Day speech. Political observers say Shastri was the first PM for whom a lift was fitted at Red Fort. It was done keeping in mind his poor health.

So, let’s reconstruct events leading up to the death of India’s second Prime Minister.

It was in January 1966 that Shastri had visited Tashkent, which was then part of Russia, or the USSR. Moscow had called Shastri, the then Indian PM and Pakistan President Ayub Khan to sign an agreement to end the war between the two warring nations. The second war between India and Pakistan had taken place during August-September 1965. The situation remained tense between the two neighbours despite a truce. On 10 January 1966, Shastri and Pakistan President Ayub Khan signed what was known as the Tashkent Declaration to put an end to the war.

Shastri was taken ill on the night of 10 January, and died an hour later. Doctors treating him described the death as a severe heart attack amidst speculation that the Indian PM was poisoned at the behest of some strong rivals.

Speculation went high because Shastri’s body had turned blue after his death. Physicians in Tashkent and also in New Delhi called it a strange occurrence.

Surprisingly, no post-mortem was conducted in Tashkent after Shastri’s death and again, when his body reached the Indian capital. Till date, it is not clear why a Prime Minister’s body should not be post-mortemed. Veteran editor Kuldeep Nayyar, who was present in Tashkent as Shastri’s press advisor, wrote in his autobiography, “Beyond The Lines”, that even he was unable to get an answer why Shastri’s post mortem was not conducted in Tashkent or Delhi.

Shastri’s family members had said that his face and body had some unnatural blue and white spots and there were cut marks on his abdomen and back of his neck. Again, there were no answers for such marks. Physicians say a body turns blue if administered poison.

Was that the case with Shastri, no one has an answer.

Conspiracy theories were further fuelled after the Indian government started denying documents—under the RTI Act—relating to Shastri’s death. The government, in its replies, said the documents were secret and disclosures were prejudicial to the interests of the country.

Anuj Dhar, the author of CIA’s Eye on South Asia, filed an RTI pertaining to Lal Bahadur Shastri’s death. Replying to the RTI, the PMO responded that there was a single classified document available, which could not be declassified as it could affect foreign relations.

An inquiry committee under Raj Narain formed by the erstwhile Janata Party in 1977 could not come up with any valid conclusions.

Strange things surrounded Shastri’s death.

In 1977, two witnesses, his servant Ram Nath and personal physician, Dr R.N. Chugh, who accompanied Shastri to Tashkent, were scheduled to appear in front of the parliamentary body, but both died in mysterious circumstances.

Dr Chugh and his family were on his way to meet the parliamentary body but were hit by a truck. The accident took the life of Dr Chugh, his wife, and two sons. His daughter survived the accident but was crippled. Ram Nath, who visited Shastri’s home, before meeting the parliamentary body, told Shastri’s wife that he was carrying some explosive information relating to Shastri’s death and would reveal it soon. But he too was hit by a car and died instantly.

What is also surprising is that if Ram Nath knew what prompted Shastri’s death why did he wait for deposing before the parliamentary body and not speak to Shastri’s wife?

And then, why did the government in New Delhi refused permission to Moscow to conduct the much-needed post-mortem on Shastri?

“India needs to ask Russia. Only then the secret will be revealed. But I doubt if that will happen,” says Dhar.

It’s 1700 hours in Tashkent, the coffee sellers have packed their boxes and will now return home, leaving the Indian PM in the company of a few sparrows and icy-cold winds.

For millions of Indians, the Shastri story is over, forever, unless Moscow decides to speak out of turn.