Most surveys or reports these days, like V-Dem, are just ideological servicing.

The Spring 2024 Global Attitude Survey by the Pew Research Center on Global Satisfaction with Democracy has scintillated conversations again with its thought-provoking findings. The survey, renowned for its in-depth insights over the years, highlights a persistent trend. While representative democracy enjoys widespread support, significant global discontent is growing with its functioning. What stands out is the strikingly high level of dissatisfaction in Western nations, particularly the United States and Canada. In stark contrast, countries in the Global South, like India, often criticized by the woke crowd as a “democracy in decline”, show remarkable satisfaction levels, with India trailing only Singapore.

INDIA AND THE IDEA OF DEMOCRACY

Before understanding India’s tryst with democracy, one must recognize the historical legacy of democratic principles in ancient India. Indeed, as a concept, democracy has been a point of contemplation and practice across different societies and eras. India is the Mother of Democracy with its rich history where democratic principles were not merely theoretical discussions but were actively practised. Increasing evidence, such as inscriptions from Uttaramerur, underscores this tradition.

Core elements of democracy, such as consensus-based decision-making and the decentralization of power among constituent units, were integral to ancient Indian society. For instance, the “samiti” and the “sabha”, both still existing today, date back to the Vedic period. Unlike Western traditions where kings wielded absolute power, the Indian concept of kingship was bound by the higher principle of “dharma”, requiring kings to govern in consultation with institutions like the “sabha” and “samiti”.

India’s democratic heritage is deeply rooted in its ancient history, with early references to “gana” and “sangha” in the Mahabharata, as well as Panini’s Astadhyayi, among others. These terms highlight decentralized governance and active public participation. The Mahabharata is particularly notable as it mentions a republican form of government with “gana” and “sangha,” indicating the presence of self-governing bodies.

One significant example is the samiti, an early form of direct democracy. The samiti allowed citizens to engage in decision-making and played a crucial role in electing kings, reflecting the democratic principles of popular choice and accountability. The king’s mandatory attendance at the samiti emphasized the importance of ruler-people interaction, showcasing the foundational democratic ethos in ancient Indian governance.

RESTORING FAITH IN SURVEYS

When confronted with surveys or comparative studies, particularly those assigning rankings to countries, the typical reaction is scepticism. These surveys have increasingly become agenda-driven exercises with little regard for research ethics, methodological rigour, or an intelligent research design that adequately incorporates the context of a particular country. This distrust did not arise overnight but is a sad reality that has taken years to develop. However, occasionally, some reports or surveys break the norm and do the unthinkable by actually engaging with the general public to gather opinions.

People, whether experienced in conducting research or not, typically assume that surveyors or so-called experts have at least interacted with the public before arriving at their results. Unfortunately, the reality of research by many organizations involves a deeply flawed process, where the voices of the public, which should be consulted as widely as possible, are often ignored. Certainly constraints like financial limitations, access, or uncooperative audiences make it challenging to conduct research. However, most surveys or reports these days, like V-Dem, are just ideological servicing, which are concluding the decline of democracy based on the opinions of a mere two dozen “experts” in a country that is preposterous by all research standards.

In this landscape, Pew’s report stands out for its vast sample size, encompassing a diverse range of people they approached face-to-face across different regions. Conducted in a dozen languages between January and March 2024, the survey’s approach is noteworthy. Equally important is how questions are framed. Many agenda-driven surveys craft their questions with such ideological bias that no rational response can be elicited. Pew’s questions were not merely devoid of biases or value judgments, but they were also simple in language, allowing respondents to form their opinions about the survey. This adherence to ethical and rigorous research methods is crucial for restoring faith in surveys. It demonstrates that when done correctly, surveys can provide valuable insights into public opinion, reflecting a genuine effort to understand the complexities of societal views.

2024 SPRING SURVEY

While not entirely surprising given past trends, the results of Pew’s survey reveal a significant magnitude of global dissatisfaction with democracy. In the United States, 68% of respondents expressed dissatisfaction, with Canada following at 46%. European countries showed even higher levels of discontent: Greece at 78%, Spain at 68%, Italy at 67%, France at 65%, and the UK at 60%. In Asia, Japan had a 67% dissatisfaction rate, followed by South Korea at 63%, Sri Lanka at 58%, Malaysia at 49%, and the Philippines at 42%. Australia’s dissatisfaction stood at 39%. Other notable findings include Israel at 54%, South Africa at 71%, Mexico at 50%, Peru at a staggering 89%, and Chile at 66%. Overall, the survey revealed that across the 31 countries surveyed, a median of 54% of people were dissatisfied with democracy, compared to 45% who were satisfied.

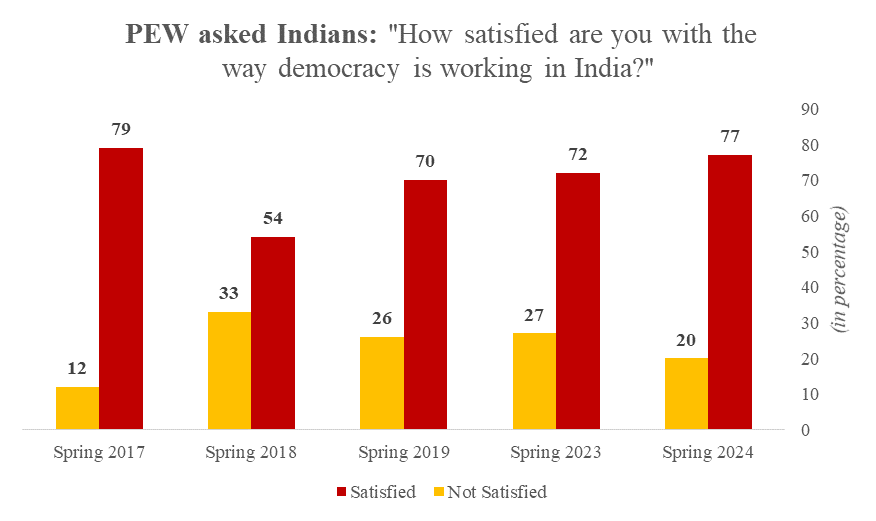

India’s satisfaction with democracy has fluctuated over the years. Still, it has remained largely stable in the seventies (in percentage), except for 2018. The chart given with this article compares and contrasts Indians’ satisfaction with their democracy over the years, illustrating this trend.

India’s responses correspond to reality on the ground, as the June electoral results reveal robust trust in democracy, with a vast population voting in sweltering heat to bring Narendra Modi for a third consecutive term as Prime Minister. Compared to the global median, Indians are 30% more satisfied with their democracy. It is, therefore, a testament to Pew’s survey that it corresponds to the reality on the ground.

In conclusion, PM Modi adds authenticity to a partnership in democracy. No elected leader in a democracy today can match the popularity of the Indian PM. Modi’s covenant with the world’s largest swathe of free voters remains unbroken. If authenticity is what some leaders lack, even as they seek eternal mandate, PM Modi has it in abundance. That is what adds to the aura of democracy’s tallest spokesperson. While global trends show decreasing satisfaction with democracy, the trust of Indians has been increasing consistently since 2018. The quality of Pew’s survey is a testament to quality research and upholding ethical standards. It highlights the necessity for surveyors to engage directly with people before forming opinions. The bias in the West towards India and many Global South countries is reflected in the limited attention given to these Pew surveys.

Prof Santishree Dhulipudi Pandit is the Vice Chancellor of JNU.