The nation will need to devise its own balance between working hours and productivity, and not rely on imitating systems elsewhere.

Recent comments by some senior business leaders on the need to work 70 or 90 long hours have made headlines, and digital storms on social media. There have also been serious discussions on the impacts. The concerns on rest and recuperation for workers is legitimate. The consternation appears to be much more in the category of white collar workers who generally have a work week of 40 hours/week. However, when doing copy-paste from western practices, it is useful to be mindful of the contexts and histories of how the developed western world attained their current status.

Underlying Economics

Prosperity of a nation and welfare of its people is seen from the income per capita, often seen as average GDP/capita as a proxy. This is about $7766 per annum for India in 2022, compared to $58487 (both Geary Khermis dollars, 2011) for USA in Angus Matheson database which enables comparison across countries over large periods of time. Note that the G-K dollars are a proxy for PPP (purchasing power parity).

At market exchange rates (MER), the per capita income in India would be only about $2800/person/year compared to about $84000/person/year in USA. For prosperity and GDP/capita to increase to the levels of a developed country, the numerator (GDP or total output) has to increase, and the denominator (population) must increase at a slower rate or remain constant or decrease, as in the case of Japan. Key enablers of the increase in GDP include the working age population, the productivity (output/worker) of the working age population, and the dependency ratio (DR) of the population divided by the working age population. Mathematically, this can be expressed incorporating several important ratios as,

Output= (Total Population)x(working age population/TotalPopulation)x(Labour Force/Working Age Population or TFPR)x(1 – Unemployment) x (Output/hour worked) x(number of hours worked/week) x (working weeks /year).

The first four terms relate to the number of labour in the economy. The last three terms related to their output. Total population & working age population are a part of demography, which is a very powerful but very slow to change force. LFPR (labour force participation rate) is the proportion of the total available as labour who are working or actively seeking work. This ratio is manageable, but the change is slow. Of those seeking work, a fraction will get employment, which is covered in the term for (1- unemployment %), the USA U-3 definition. In an ideal scenario, the number working towards growing the economy will equal the total number in the working age, i.e., LFPR will be 100% and Unemployment will be 0%.

Output per hour worked, or hourly (daily/annual) productivity, depends on several factors. These include but are limited to: a) Technologyb) Systems in workplace c) Systems at macro-level d) Competencies& Skills levels of labour e) Health & welfare of labour f) Job levels, and of course f) Capital & its productivity. Some of these are not in the direct control of labour. Some of the factors can have undesirable side-effects.

For example, use of a high level of technology can have the severe societal effect of decreasing the employment levels in the short or even medium term. Macro level systems depend on several macro level factors including politics & trade unionism, with their own effects. Some factors, like large scale skill development or increasing the health & welfare of the population, need extensive resources or long time periods in large countries. Number of weeks worked per year depends on the vacation period, holidays, and weekends that labour works. In contrast, number of hours worked per week is more directly in the control of labour itself.

Avoid Copy-Paste from the West

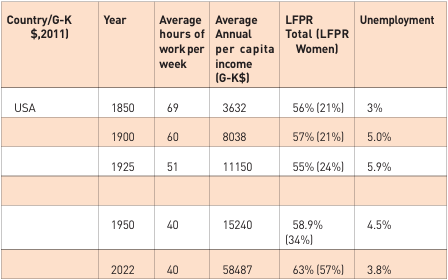

It is quite common that at systems, practices & processes in the developed countries in the west are taken as a given to be adopted in India. Without debating the merits of any such system here, we examine the evolution of the work week of USA with its evolution as a developed country.

Note that by the year 1890, USA had reached the goal of becoming a developed country, hence the period before 1890s can be considered as the period for a country striving to become developed. To that extent, it reflects the situation in which India is currently. USA per capita annual income in 1900 was $4091 (MER), which is about 130% more than the income in India in 2024. The same analysis can be done for Germany, which in the year 1900 had developed to the same per capita income as India has in 2024, with average working hours of 65-70 per week. Japan perhaps presents an extreme in this.

Without going into a multivariate regression analysis, the data suggests a correlation in the path to a developed economy and the number of hours worked per week. In the mid-1800s, in addition to the work per week, the working conditions were in USA were such that moving to an urban area for industrial work was considered as a definite shortening of life span. German workers have gained as much as 6 inches in height due to better nutrition levels now. Fortunately, working conditions in most work places in India, and particularly for organized labour, are much better.

Productivity Imperative for India

The population of India is expected to grow to about 1.69 billion by 2055. India is enjoying a demographic dividend. The fertility rate (TFR) of India has been decreasing sharply, and it is expected that the window of demographic opportunity will close faster than expected, by about 2055. India thus has a narrowing window to lift the prosperity levels or GDP/person of the population.Currently the GDP of India is about $3.9 trillion. The working age population is 0.91 billion. LFPR is about 60%, with Female LFPR at 37% (rural-42%, urban-25%). As per the PLFS, unemployment is about 3.2%. Privilege leave (4 weeks), casual Leave (2 weeks), Sick Leave (2 weeks), Declared Holidays (2 weeks) reduce the weeks of work per year to about 40-42.

Viksit Bharat envisages that by 2047, Indiawill have a GDP of $38 trillion, with a working age population of about 1.1 billion. LFPR will grow to about 75%, with Female LFPR at 45%. It is difficult to envisage that unemployment will drop to below the 3.2% estimated by PLFS. Given that India is a complex country, we assume that the weeks of holidays will remain the same and work weeks will continue to be 40-42 per year. Inserting these numbers in the equation given earlier and dividing the equation for 2047 by the equation for 2024 we narrow down the productivity part to two terms in a productivity equation,i.e.,(Output/hour worked)(#hours/week) in 2047= 6.4(output/hour)*(# hours/week) in 2024. This increase is indeed a tall order.

To arrive at the number of hours of work needed in 2047 for a developed India, we further examine the ratio of the first term, (Output/hour worked) in 2047 to the same metric currently. For this, an estimate of the labour productivity growth is needed. The USA labour productivity growth in the period 1990-2000 reached 4% per year. However, since USA was a well-developed country by then already, this growth can be expected to be higher for a developing country. China achieved labour productivity growth as high as 8.9%/year from 1995-2010, and about 7% over a sustained 30-year period. India has managed a labour productivity growth rate of about 6%/year for short sustained periods.

With digitalization and the current very low productivity, and recognizing the differences between the democratic Indian system and autocratic China system, an optimistic labour productivity growth rate of 7%/year is taken. At this CAGR over 23 years of labour productivity, the ratio of Output/hour in 2047 divided by Output/hour in 2024 becomes (Output/hour) in 2047 = 4.7 *(output/hour in 2024). That is, the multiple of 4.7 times out of the required 6.4 times can be provided by the increase in (Output/hour). This then requires that the (number of hours worked per week) in up to 2047 increase by 6.4/4.7 i.e., by 36% over the hours/week worked in 2024. The average number of hours worked per week in India are 47 – 55 hours. Hence the required number of hours per week become 1.36*50, which are 68 hours per week. These would be actual hours of production, and exclude commuting and lunch break times. Countries in their journey to developed status have sustained this pace over long periods, but only Japan has sustained this pace in recent times. It will not be sustainable in India.

Path Forward

With the demographic window closing faster than expected, and the importance of becoming a developed country rapidly to provide a much better quality of life for its people, India will need to find levers and create solutions. Demography in numbers will change very slowly and is not a usable lever. Quality of the demographics like health & education can be changed faster and become an imperative. Increasing Female LFPR from 45% to 70% will

increase overall LFPR by another 10%, and decrease the number of productive work hours per week to 60 hours. However, this change will require societal acceptance, and could result in decrease in male employment. Another lever is increase in the number of weeks of work per year. Some data suggests that against the 40 weeks per year taken in calculations here, Indians work about 36 weeks per year. If work weeks per year increase from 36 to 40 per year, number of hours/week can be reduced by about 10%. This increase is unlikely. The most important lever is output/hour worked. If the CAGR of productivity growth can be increased from 7% taken here to 8.5%, the number of work hours per week can even be reduced by 2% to about 49. Conversely, if the CAGR of labour productivity is decreased in this estimation from 7% to 5.5%, then the hours work per week required increase to about 82 hours. Increasing the Output/hours becomes the most important productivity imperative for India. This implies that key drivers will be Technology, Education/Skills/Health of labour. High value addition activities are also likely to be more capital intensive. Note that GDP is value added, and not merely increase in the revenue. Therefore, along with the increase in value of output, efficiency and cost control will be important.

The path forward will be very challenging. An encouraging aspect is that there has been a significant increase in TFP (total factor productivity) in India in recent years (https://sundayguardianlive.com/opinion/total-factor-productivity-trends-china-india-2). From amongst all imperatives including labour intensive growth, keeping in mind broader societal implications, India needs to focus on moving up the value chain in value produced per hour of output.

Vivek Joshi is an Advisor at A-Joshi Strategy Consultants Pvt Ltd, Mumbai. Views expressed are personal.