There was a time when Indian writers regarded the English language with suspicion or post-colonial contempt. But today, English is being Indianised in our literature, writes Nirmala Govindarajan.

The English language is India’s most abiding colonial legacy which most Anglophone Indians today, ironically, don’t even associate with the West. In this sense, English has become an Indian language in its own right. The sheer variety of Indian writing in English published in the last 50 years or so further attests to this fact.

Through their fiction and poetry, Indian writers have reinvented—Indianised—the English language to a great extent. Dipa Chaudhuri, Chief Editor, Om Books International, explains, “Given the sheer expanse of Empire, its language was bound to be appropriated, hijacked and ineluctably altered by its colonies to produce a body of literature expressing culturally hybrid to purely localised experiences. Today’s writing style is an index of what typically happens when the language of a deemed ‘elite’ is appropriated by a deemed ‘aspirational class’—a language is dissected and reinvented.”

Today, the younger generations of Indians are at one remove from their colonial history, and this distance is reflected in their relaxed attitude towards English, as opposed to the anxiety their colonial ancestors might have felt.

Udayan Mitra, Publisher-Literary, HarperCollins Publishers India Limited, says, “India is in the somewhat unique position of having a rich colonial history, which is linked to a large cross-section of the population being English-speaking. But a significant young demographics was born after India’s Independence, and even after the liberalisation of the economy, and that generation is thus quite detached from that colonial history. This makes for a very interesting situation where many writers from India choose to write and express themselves in English, while writing about and capturing contemporary experiences about today’s India, which is increasingly removed from its colonial history.”

Contemporary Indian literature is full of examples of writers using English as a tool to convey experiences and episodes that don’t necessarily occur in Anglophone milieus.

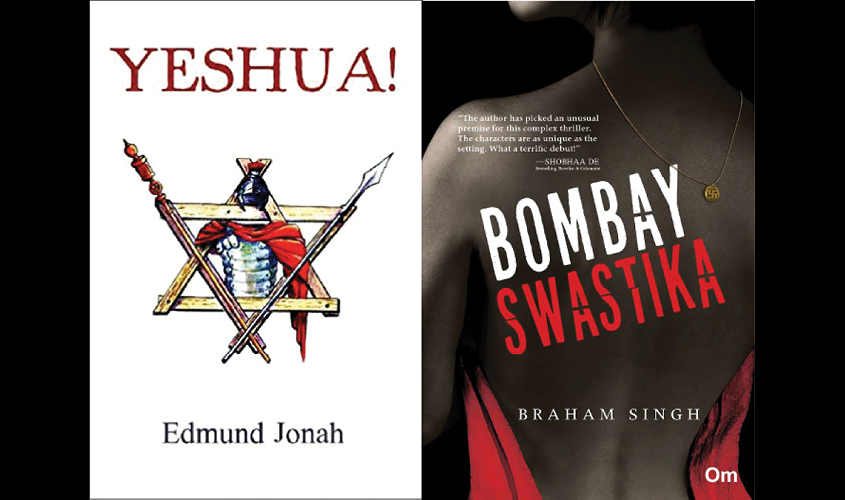

Dipa Chaudhuri gives us a list of writers who have done that expertly: “Edmund Jonah in Yeshua!, Braham Singh in Bombay Swastika, Sanjay Chopra and Namita Roy Ghose in The Wrong Turn: Love and Betrayal in the Time of Netaji. These are writers with great imagination, fine storytelling skills, and mastery of the language—English—they have chosen to write in. Add to that their in-depth knowledge of history.”

Author, editor and co-founder of the Bangalore Literature Festival, Shinie Antony is among those who believe that most Indian writing in English is driven by a multilingual imagination. “The unique selling point of Indians writing in English today is that they are telling their own stories in their own tongue—be it English as it is spoken in Tamil Nadu or in Haryana. Dialogue in a book as in a movie has to fall into the ear and not at the ear. And this is possible when language is flexible and sensitive to nuance, travels from remote corners with its original crispness intact,” she says.

So you find currents of internationalism as well as regionalism in Indian writing now. “The writing we encounter now is more sophisticated, more worldly-wise and international, while digging deeper into local vocabularies, specificities and truths,” says Karthika V.K., Publisher, Westland. “Indian writers don’t need to look Westward for readership or attention in the way that the market and media seemed to require of them five or 10 years ago. Look at the bestseller lists and popularity charts—they are full of Indian writers who are published exclusively in India. Perhaps this has something to do with the new tone and confidence in their writing.”

With confidence comes a new wave of creative energy. As Shinie Antony says, “All use of any language is creative, since we adapt our communication skills to what we are trying to communicate. It is language masquerading as ‘literary’ that is a problem because it is self-conscious and brags. Any language organic to the telling is creative and fluent and can only add to the book.”

The biggest strength of contemporary Indian literature in English is its scope, how it can accommodate a range of literary styles and attitudes. Dipa Chaudhuri sheds light on this variety: “There are writers of mass-market pop literature, who are not the staunchest proponents of a certain kind of English. There are other writers who use the language deftly to translate, write librettos, novels of Tolstoyan sweep, memoirs, sonnets in iambic tetrameter, or a clutch of stories on animals. Then there are writers who know how to recast the language according to the exigencies of the genre, the theme, the historical and socio-political contexts…”

One more reason why English has thrived in this country might have to do with the lack of academic institutions safeguarding it. Chaudhuri continues, “Is it possible or even necessary to preserve a ‘pure’ English? To have an academy that codifies and regulates its acceptable usages, banishes all forms of impurities and contaminations? Or is it better to let the language evolve through assimilation and amalgamation, as it has? As for the state of the English language in India, the absolutist premise of a standard English has long been supplanted by the many different forms the English language has taken here.”

These Indian forms of English have actually made several significant contributions to the Queen’s language. In 1984, for example, the term “tarka dal” found a place in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED). “This is an ongoing process,” says Udayan Mitra. “Every year, the OED includes more and more ‘Indian’ words, and this will continue to happen.”

More recently, the Tamil term “aiyo”—an expression of distress or regret—was awarded a place in the English dictionary, to Karthika V.K.’s surprise. She says, “I am sure there are dozens of other words that speakers of different languages mash up and invigorate by doing so. But honestly, I no longer look to dictionaries as the sole providers of sanction for the use of words—it’s the context that decides it.”

So in the Indian context, spoken English feeds into its literary variant, shaping the way writing is done. As Udayan Mitra says, “What is more interesting is the way in which spoken English is being redefined by the current generation of Indians, including not just many words and expressions from local languages but also a mixture of English and Indian languages in the construction, grammar, and even the thinking behind the language. This language is beginning to be captured in English writing in India too, and it makes for very interesting reading sometimes, if you think of the way it departs from the language that was used a few decades ago. Of course, this is something that is not unique to India. Contemporisation of language is a worldwide phenomenon. But it’s very interesting in India because of the interplay of a number of languages involved.”