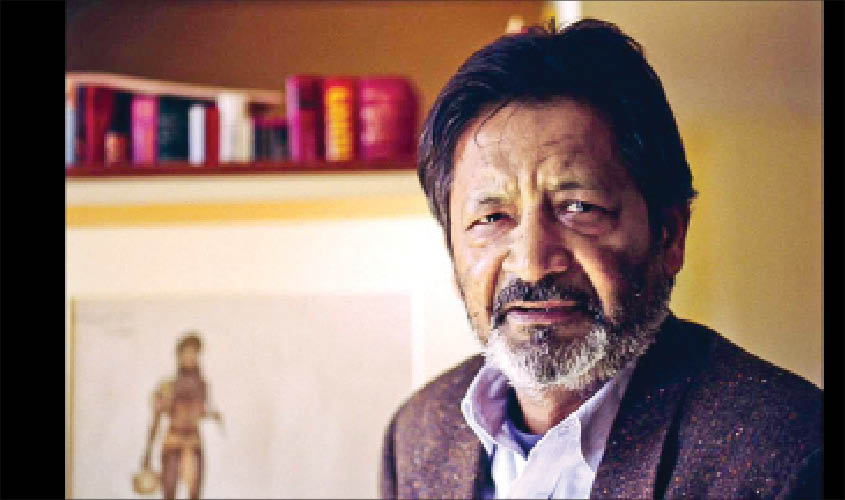

V.S. Naipaul did more to push the generic boundaries of fiction and travelogue than any other writer of his generation. But can we reconcile his achievements with his vices? By Vineet Gill.

Some writers never feel at home, anywhere in the world. V.S. Naipaul was perhaps the greatest exemplar of this existential homelessness. Indeed, the yearning to escape and the ambition to write are different manifestations of the same impulse in Naipaul. His writing, in Bharati Mukherjee’s memorable phrase, “is about unhousing and remaining unhoused”.

Naipaul left colonial Trinidad, his native land, because “small places with simple economies bred small people with simple destinies”. In England he was homesick, but with no home to return to. “Do not imagine that I am enjoying staying in this country,” he writes in a 1954 letter to his mother. “This country is hot with racial prejudices, and I certainly don’t wish to stay here. My antipathy to a prolonged stay in this country is as great as my fear of Trinidad.”

In the difficult, early stages of his literary life—so gloriously mythologised in his work—Naipaul was a writer struggling to find his bearings. The legendary writer’s block he suffered as a student at University College, Oxford, and later as a freelancer in London, was the result of his failure to model himself on distinguished British belle-lettrists, such as Somerset Maugham or Evelyn Waugh. Mimicking others, though, was never an option for him; the writerly imperative, as Naipaul understood, was to develop one’s own voice, and discover one’s own material.

Naipaul made an imaginative return to his childhood in Trinidad for his early books, casting his lot with the same simple destinies he’d once sought to escape. The first worthwhile (in his own estimate) sentence he ever wrote was what became the opening line of his 1959 book of short stories, Miguel Street: “Every morning when he got up Hat would sit on the banister of his back verandah and shout across, ‘What happening there, Bogart?’”

The dramatic energy in this Port of Spain scene, suggested by that sentence, is rivalled only by the drama of Naipaul’s account of writing the scene. This account appears in his wonderful, probing essay, “Prologue to an Autobiography”. The author is in the “Victorian-Edwardian gloom” of the freelancer’s room at the BBC offices in London, sitting at an old typewriter. The inaugural sentence writes itself, as though magically, on the sheet of “smooth, non-rustle paper”. Thus descends the muse and thus begins an illustrious career.

The only problem with this narrative is that it may lead some to believe that Naipaul, with his moment of discovery, his moment of clarity, had found his comfort zone as a writer. In truth, he never managed to allay his anxieties about content and form. The fundamentals of writing—what to say and how to say it—continued to unsettle him long after he had published his first six books, including A House for Mr Biswas, which was a resounding critical success. He experimented with genres without ever caring for any of the conventions of generic writing. In his corpus, we find reportage which is really autobiography; we find autobiography disguised as novels; and novels disguised as travel books.

The travel books, of course, earned him much disrepute. He lost old friends (Derek Walcott), and made new enemies (the formidable Edward Said) solely on the strength of his travel writings. People attacked him for his lack of sympathy, his lack of love for the characters and landscapes portrayed in the series of books on India, the Islamic world and the Caribbean islands.

There’s no way these charges can be disputed. For a man of his intellectual capacity, Naipaul was too rigidly opinionated, and at the same time naively unsuspicious of his own opinions. This tendency sometimes crept into the writing, distorting the prose, reducing it to the level of soulless caricature. In one of his essays he records his meeting with an Indian man on a flight to Paris. “I enwy you your wegetarianism,” the man tells him, apparently in a thick Indian accent that Naipaul is childishly amused by. It is this caricaturing that many of Naipaul’s detractors, as well as his admirers, find irritating. And this is valid criticism.

But is it fair to expect a balanced appraisal of postcolonial cultures and histories from his travelogues? Or from any travelogue for that matter? Was Graham Greene, was Mark Twain, ever a level-headed traveller? Were they judged on the same parameters? It may be that Naipaul’s readers felt betrayed by him because he was not a white Orientalist, because he was an insider making the outsider’s case (this was the gist of Said’s argument against him). Or else, it may have been a personality flaw rather than an intellectual blind spot that affected Naipaul—after all, he was someone who enjoyed being an outsider and regarded each attack as a form of validation.

The case against Naipaul doesn’t end here. It became overwhelmingly personal during the final decade of his life, not least after the publication of Patrick French’s biography, The World Is What It Is, in 2008. Once, he was considered nothing worse than a hot-headed fool and a pitiless curmudgeon. (Saul Bellow said of him, “After one look from him, I could skip Yom Kippur”.) Now he was labelled a misogynist and much worse (which he no doubt was).

After his death last week, I was struck by the general tone of contempt in which his name was being mentioned on social media. There was none of that “monster-but-genius” talk, none of that moral ambivalence a reader might feel when separating the teller from the tale. There was just plain, one might even say Naipaulean, contempt for the deceased. These disgruntled souls, I believe, are the kind of people for whom the question has been settled: bad guys can’t make good art.

Yet art is a more complex game than that. Paul Gauguin, the painter, was a horrible man by all accounts. But was he the same man when he was painting? In a 1987 essay for the New York Review of Books, Naipaul quotes a line from Proust that directly concerns this, as it were, split-personality disorder in writers: “…a book is the product of a different self from the self we manifest in our habits, in our social life, in our vices.” I hope we don’t end up forgetting Naipaul’s writing self entirely while trying to remember his vices.