K.G. Subramanyan was one of India’s most versatile modernists. The ongoing exhibition of his drawings, at Delhi’s Triveni Kala Sangam, serves as another reminder of his genius and his extraordinary aesthetic range, writes Bhumika Popli.

I am by nature a fabulist. I transform images, change their character, make them float, fly, perform, tell a visual story. To that extent, my pictures are playful and spontaneous. I do occasionally build round a well-known theme, and give it new implications.” The late K.G. Subramanyan said this to art historian R. Siva Kumar in a 2014 conversation.

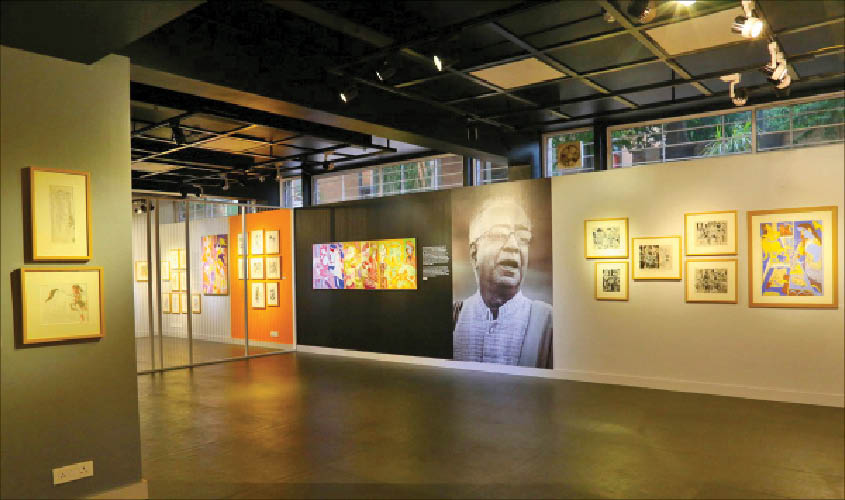

We see the same playfulness and spontaneity in his drawings, now on display as part of the exhibition, Women Seen and Remembered: Drawings of Women by K.G. Subramanayan (1953-2016), at Delhi’s Triveni Kala Sangam.

The women in Subramanyan’s drawings are invariably placed within domestic scenes, around floral and animal motifs and often as standalone figures. The figures appear in dynamic, as though they were caught in the midst of movement. These drawings come across as chance encounters or glimpses rather than elaborate, finished works.

Three galleries at the venue are hosting the exhibition, comprising some 250 works by Subramanyan, not just plain drawings in the conventional sense of the word, but sketches made with oil plaint, watercolours and crayons as well. The exhibition also includes some works on terracotta.

The artworks are displayed chronologically, from the 1950s to the year of the artist’s death, 2016. A statement by Amal Allana, curator of the show, reads, “The works in the exhibition move from the slumped, the domesticated body of the woman of the 1950s, to reveal how she transforms into a self-aware coquette in the 1970s, presenting herself in her full-blown, stark sensuality. With the 1980s and ’90s, a new, threatening aspect of the woman appears as she is seen masked, presenting a double image of herself. Refining her ammunition to deal on more equal terms with her male counterpart, also masked, they together re-enact the age-old antagonistic war of the sexes. From the 2000s the woman is rarely shown singly or coupled with the man, instead, Subramanyan’s compositions show her to be an involved participant in larger, social issues. From around this time, the artist delineates the woman in her avenging avatar, as the goddess Mahishasura. Mounted on a tiger, the woman is charged with cosmic energy and she is seen in all her glorious resplendent beauty.”

In some of the drawings, one can also read Subramanyan’s poems placed adjacent to the languid figures done in oils and ballpoint ink. One of the poems is titled “G.”

See G.

There she comes waving her unsleeved arms.

Is dressed in a spree

That seems a coarse bed-spread

Patterned with ugly roses

Resembling bleeding sores.

And her awkward gait confirms

Her thighs are fat.

She stops and smiles…

According to a catalogue essay on the artist’s poetry and artworks, written by art historian R. Siva Kumar, “His poems and late drawings narrate the story of his exploration and discovery of the geography of the human body and the landscape of dimmer emotions. Thus in them, the viewer and the viewed are inextricably intertwined.”

Subramanyan was undoubtedly a towering figure in Indian art. He painted prolifically, made sculptures, prints and murals, besides devoting a good part of his life to critical writing and poetry. With his diverse use of media and mastery of technique, Subramanyan was among the most versatile artists in modern Indian art. Along with many national and international honours, he was also awarded the Padma Vibhushan in 2012.

This Kerala-born artist, who taught at Santiniketan, remains a mentor to many youngsters. His visual vocabulary was richly interlaid with symbols of mythology, eroticism and folk traditions, making his artistic language distinctive. But he always detested making art for an audience. In his essay “New Perspectives in Art”, he praises the ancient cave painters on this count. “…the most important feature of today’s art practice—making things for there to respond to—was of no great importance to cavemen artists nor the notion that we now cherish of the picture space. For them, the painting was probably part of a secret ritual, and its aesthetic qualities.” This holds true for Subramanyan himself.

This exhibition, organised by Art Heritage Gallery in collaboration with The Seagull Foundation for the Arts, is on view till 9 September at Delhi’s Triveni Kala Sangam